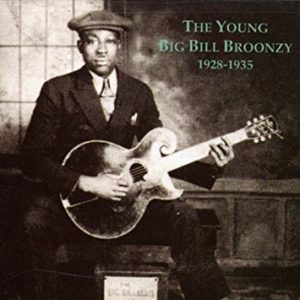

Big Bill Broonzy is synonymous with pre-war Chicago blues. One of the first artists to make his way to the Windy City, he became one of the most influential artists in blues history. Here are 10 things you may not know about the rural-to-urban storyteller.

1. Broonzy reinvented himself many times. He made his own cigar box fiddle at the age of 10, and with help from his uncle, learned to play.

1. Broonzy reinvented himself many times. He made his own cigar box fiddle at the age of 10, and with help from his uncle, learned to play.

After he moved to Chicago in the 1920s, he switched from fiddle to guitar, learning from Papa Charlie Jackson. Broonzy worked as a Pullman porter, cook, and foundry worker until he mastered it.

Broonzy was also one of the first bluesmen in Chicago to play electric guitar, beginning in 1942, though his audiences preferred the acoustic sounds of the South.

2.Including his own autobiography, Big Bill Blues, several biographies have been written about Broonzy. Perhaps the most researched, and accurate, is the book, I Feel So Good: The Life and Times of Big Bill Broonzy by Bob Riesman. Riesman used a myriad of sources to separate fact from fiction, and truth from storytelling. Among the information Riesman uncovers is the truth about Broonzy’s military service in World War I, his date (and place) of birth, and his real name, which is Lee Conley Bradley.

3. The first audition recordings Broonzy made for the Paramount label were rejected — but his persistence paid off. In 1927, his first release, recorded with his friend John Thomas on vocals, was issued by the label. Credited to Big Bill and Thomps, the record “Big Bill’s Blues” with “House Rent Stomp” on the B Side was not well received, but it did begin his recording career.

During the course of his life, Broonzy would copyright over 300 original songs. He recorded and released 260 between 1927 and 1952.

4. Broonzy replaced Robert Johnson at Carnegie Hall in 1938. Some say that performance may have garnered him the nickname “Big Bill” by the white attendees. The aforementioned recording credits prove this false, although it is true he did perform at the famous From Spirituals To Swing concert. Organizer John Hammond asked Broonzy to perform in the place of the recently deceased Robert Johnson. He performed one song, “It Was Just a Dream,” with pianist Albert Ammons.

Since this was Bill’s first performance in front of a white audience, he was so overwhelmed that he got caught in front of the curtain when it came down. He also forgot (or didn’t realize) that he had another song to do during the second half of the show, so he left Carnegie Hall and caught a bus home. He did return the following year however, on Christmas Eve, 1939, and performed two songs, once again with Ammons on piano.

5. As many other bluesmen of the time, Broonzy used several names when recording and performing. Some of those include Willie Broonzy, Big Bill Broomsley, Big Bill Johnson, Little Sam, H. B. Broonzy, Sammy Sampson, Chicago Bill, Willie Lee Broonsey, and William Lee Conley.

6. Arguably his most famous song was “Key to the Highway,” credited to Broonzy and “Chas” Segar. Segar recorded it first, in 1940, as a 12-bar, up-tempo tune. Shortly thereafter, Jazz Gillium recorded the song as a slower, 8-bar arrangement with Broonzy on guitar.

Broonzy returned the favor, recording it himself, with Gillium on harmonica just seven months later. That version became the standard for future recordings, being acknowledged by its induction into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2010. Dozens of other artists have covered the song, including Little Walter (1958), Derek and the Dominos (1970), John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Luther Allison, B. B. King, and Sonny Landreth.

7. Broonzy goes to Europe. When a younger generation of electric blues artists began ruling the Chicago scene, Broonzy found a new audience in the white, folk music lovers of both the United States and Europe.

Being a versatile artist with an instinct for professional survival, Broonzy first went to Europe in 1951. He was greeted by enthusiastic fans, and critical acclaim. Subsequent European tours found him influencing young British artists including John Lennon, Eric Clapton, Ray Davies, and Rory Gallagher. Broonzy felt most at home in the Netherlands, where there were no Jim Crow laws nor racism. He fell in love with a Dutch girl by the name of Pim van Isveldt, and fathered a son, Michael, who still lives in Amsterdam.

8. During his travels on the folk circuit, Broonzy became friends and performed with artists that included Pete Seeger, and Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee. His song, “Black, Brown and White Blues,” became a protest anthem against racism. In spite of the song’s critique of discrimination, some fans in the black community did not approve of his shift from blues to folk music. Regardless, upon returning from his last tour of France in 1956, he became a founding faculty member of the Old Town School of Folk Music in Chicago.

9. Broonzy’s final recording session was in 1957 by Cleveland disc-jockey, Bill Randle, and Chicago radio personality, Studs Terkel. The morning after the final session, Broonzy was checked into the hospital. He was suffering from throat cancer that was quickly spreading to his lungs. His voice gone, he continued to perform locally on guitar, for as long as he could.

10. Big Bill Broonzy died on August 15th, 1958, in an ambulance on the way to a Chicago hospital. His funeral was held at the Metropolitan Funeral Parlor and was attended by throngs of fellow artists and fans. Gospel great Mahalia Jackson performed a hymn during the service.

As a nod to Broonzy’s anti-discrimination beliefs, folk music artist and co-founder of the Old Town School, Win Stracke, selected the pall bearers. Three were black, and three white, including himself, Terkel, Tampa Red, and Muddy Waters.

Stracke’s daughter, Jane, explained, “He did it very consciously. He wanted it to be kind of a lesson.” Also during the service, a recording of Broonzy himself, singing “Swing Low Sweet Chariot,” from the Randle recording session the previous year was played. This prompted reporters from both Chicago newspapers to use the exact same phrase: “Big Bill Broonzy sang at his own funeral.”