Editor’s note: King Biscuit Attendees! Get a chance to see Carl in person discussing big issues in the blues at the third annual Call and Response, The Blues Symposium begins at noon on Saturday at the 28th Annual King Biscuit Blues Festival at the Malco Theater on Cherry St. in Helena and is free to the public

How do artists like Bobby Rush, Chicago blues guitarist Carl Weathersby, Beale St. veteran Blind Mississippi Morris, and Memphis producer and guitarist Brad Webb stay true to their muse and survive in the 2013 music world? Join King Biscuit’s own award winning blues journalist Don Wilcock and Matt Marshall, editor of American Blues Scene, the most popular blues website in the world, as they ask the tough questions about staying in the game of pouring your heart out on blues stages around the world from Carnegie Hall to juke joints in Tupelo, Arkansas.

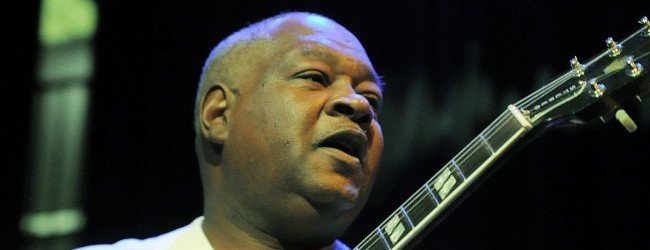

“If I wasn’t so old, I don’t know if I would continue to do this stuff,” says Carl Weathersby, talking to me at the crack of noon after an eight-hour session the night before at Chicago’s late-night blues club, Kingston Mines. Weathersby at 62 has never spent a day bent over picking cotton, but he’s paid his dues. He was stationed at Hue, Vietnam, with the 101st and 173rd infantry in ’66. He’s been a steel worker, a prison guard, and a police officer, telling one interviewer in 1998, “If it came down to eatin’ a guy’s arm off his body, I could do it if I had to.”

He likens long gigs like Kingston Mines to football practice where the coach makes things tougher than the players will ever encounter in a real game. “The coach told us, ‘Some of you guys going to the hospital from this practice. Your ass is gonna be totally dehydrated. When you get in the game, the game is gonna be easy because you get a whole lot more rested than you get here.'”

He claims that singing and playing guitar is more of a job than fun, but he admits he still enjoys connecting with an audience. “Yeah, the ones that come in and see me? It should be 20,000 people in here. There should be another 100 people in here. You gotta play for the ones that show up. That part of it – entertainer? I kinda like when you get to the part of the night. I can just take a chair, sit down in front of the stage here and just play whatever the hell I want to play. Know what I mean? No blues police, no rock police. Just play whatever I want to play.” Carl first met Albert King as a teenager when his father brought the blues giant home with him. Carl thought Albert was just another of dad’s mechanic friends, but when King heard the young man playing “Cross Cut Saw,” he revealed himself as the author of the song, and Carl ended up spending two years on the road with him as his rhythm guitarist. With seven solo CDs to his credit, the best being “Restless Feeling” on Evidence, Weathersby has also been a sideman for many blues artists including Hubert Sumlin, Carey Bell, and has recorded six albums with Billy Branch’s Sons of Blues. He is featured with Branch at this year’s King Biscuit Blues Festival and will be my guest at the Biscuit’s third annual Call and Response Blues Symposium at noon on Saturday, October 12th in the Malco Theater. Weathersby toured China with the late great Swiss jazz band leader George Gruntz, an experience he describes as standing on the edge of a worm hole ready to go into cyberspace at any moment. His sophistication on guitar injects steroids into his live performances with acts like Mississippi Heat and Nora Jean Bruso. And although he poo poos shows like the one he will do with Billy Branch as boring, he is sure to push that Chicago blues veteran to a higher level during their Biscuit bash.

Carl Weathersby: When you play with Albert (King), you play chords all night. He doesn’t let anybody sing or anything like that. He was going upside down and backwards. It was kinda rough. In his band all you did was play your particular instrument. The piano player would get a solo maybe, but horn players and guitar players would get no solos.

Don Wilcock: What was so different about his left-handed playing that made that so difficult?

Upside down and backwards.

But it sounded like a right handed guitar to me anyways.

Naw, naw. Stuff you would hear. When he played backwards a lotta stuff that happens you can tell that he’s doing something different. He played the guitar upside down, and it’s backwards when you look at it. A right handed person would do something so it sounds different. It’s confusing, like watching somebody run backwards. It’s really what it’s like, and then you put your feet where the head would be. So, you pretty much just wastin’ your time watching. You might as well just start listening. Even on the guitar, if you stick the notes with your pickin’ hand, it makes a difference in the way it sounds if the strings are being plucked up or down. I mean they make some music calls for you to do upstrokes. If they write stuff out, they’ll write it out. It’s an inverted means you pick the note up. If it’s a regular beat, it means pick it down. So it takes a big enough difference the way it sounds for people that write for guitar they indicate which pluck it pattern you should use.

When you were a kid learning to play “Cross Cut Saw,” did you realize that he played that way?

No, Just sounded like he was a guitar player. They didn’t even have pictures of him out on the albums. Back in those days I guess it wasn’t a wise thing to do to put a black person’s picture on the album. They normally didn’t do it back in those days, and “Crosscut Saw” was on a 45 as far as I know. So there were no pictures of Albert King lying around. So, unless you knowed that was Albert King I guess anybody could have showed up and pretended to be him. If they could’ve played like him, they got away with it. You could’ve got away with it. The only blues guy I could really identify was B. B. King because I’ve seen him on TV quite a bit. He had a few posters around, but I couldn’t have picked out Muddy Waters or Howlin’ Wolf, or any of ’em because you don’t know what they looked like.

Right. Yeah, they wanted to sell to young white kids, and their parents didn’t want them listening to African Americans.

Yeah, I guess. The record companies, I don’t know. These guys always were pretty cheesy dudes, people, every one of ’em I run into. I’m serious, man.

You mentioned last week that you were working on a new album. Who is going to produce the album?

Probably me.

I remember when I interviewed you in 1999, you’d had this guy John Snyder produce two of your albums, and you said he’d never heard you live, and when he heard you live it changed his whole vision of who you were. Has that been a problem with your albums in the past, getting the sound the same as it is live?

It ain’t gonna sound the same as it does live. People in the studio try to take over and control too much, too many different things, volume, tone and all that stuff. So it just don’t sound the same live as it would sound in the studio. That’s just how it is. You never get that live sound. It always sounds different in the studio.

Well, I suppose it’s because you don’t have the response from the audience to get you geared up.

You got too many people tellin’ you what to do in the studio, too many rules, too many regulations, and all that stuff. Playing live is just completely different. I never seen anybody play a live show at the low volume they want you to play in the studio. If you want to do something that sounds live, it’s gotta be live.

I remember you’re telling me you’d recorded in Louisiana one time, and you wanted your own equipment so you drove 1200 miles to the studio as opposed to taking a plane.

Yeah, yeah. It may sound weird, man. It’s the flavor of the month. You go in the studio. They have all this stuff around. They tell you how much all this stuff is worth. Most of the people I listen to play don’t have all this weirdness, and you gotta have a bullshit amp and all that because that ain’t what they go by. Just by the sound. So they try and put me with some amp that I hate. People started on all these pedals. It always sounds beautiful for somebody to do that, but that ain’t what I do. So, I’d rather drive down there and take my own amplifier that I can use to record with. You gotta do a little bit more than say an amplifier is great.

You’ve never been a purist. You put some Motown into your sets. I can remember seeing you at King Biscuit in 2008. You did Glen Campbell’s “By The Time I Get to Phoenix” in your set.

I did that because Isaac Hayes did that song. I never heard Glen Campbell do it.

Really? He had a huge hit with it about 45 years ago.

Yeah? Isaac Hayes had a hit with it, too. I heard Glen Campbell’s version of it, and I went, “How the hell did Isaac Hayes get what he got out of that song by listening to it?” But I guess that’s kinda what happened with John Hiatt’s “It Feels Like Rain,” and by the time I finished playing it that day, that song had morphed into something. I guess we could’ve wrote words to it and just called it ours.

So, you’re going to play at King Biscuit with Billy Branch and the Sons of the Blues. How long has it been since you guys played together?

Uh, been a pretty good while. I guess it was the last time I played in Helena with them. I was on a show with ’em. Yeah.

You don’t sound too enthused.

No, I’d much rather be down there with my band so I can do what I do. It’s kind of hard doing what you do with someone else’s band. Billy’s band is tailored for him, you know. It’s just that you gotta make a living. You gotta make money how you can. I’ll show up down there in Helena and play and get my money and come back with you the next day and do the (Call and Response Symposim).

I’ve seen you play with your band, and I’ve seen you with Nora Jean Bruso live, and I’ve seen you with Mississippi Heat live. And you always steal the show.

No, I just do what they’re paying me to do. That ain’t saying that people rather see me do is play with other people, you know what I mean? I don’t know. There’s so much weirdness going on with this music right now. If I wasn’t so old, I don’t know if I would continue to do this stuff. You got so many people that are just happy to be playing, and they’ll play for pitchers money, you know what I’m saying? I just got insulted last night. Man, you guys want to pay me on New Year’s Eve what I can make on a Friday or Saturday, and you’re charging double to get in? Now, I’m not asking you for whiskey money or food money. I need to get better than one percent of the door. (Chuckles) You’d have thought I asked him for $30,000 for the night. This is some shit. I don’t go do a gig to get away from my wife. I got a daughter in college. I try to eke out a living doing this stuff, but, man, it’s hard.

Are you going to let Billy Branch do “Scratch My Back” at King Biscuit?

He can do “Scratch My Back” all he wants to. If he plays that, I’m going to the place where they got the Coca Colas and 7 Ups and stuff, and I’ll sit over there and drink one until he gets through with that.

(Laugh) Why do you hate that song so much?

My grandmother played that mutha fuckin’ song all day, every day. Now, look, I’ve heard that song enough to do me a lifetime. Got no problem with Slim Harpo. He can scratch that thing all day long. I’m not gonna play that. I refuses to play that song! You can cut my Goddamn fingers off. I ain’t playin’ it. That song and “Help Me.”

Sonny Boy’s song?

Yeah.

They love that in Helena, you know.

Yeah, well, there’s certain people that don’t need to sing “Help Me.”

(Laugh) Oh, Carl. You’re a piece of work.

Man, the whole premise of that song is just fucked up. “You gotta help me. I can’t do it all by myself.” Do some of it, you mutha fucker, and shut up. “Might have to cook. You might have to sew.” It’s like, man, you don’t ever need to sing that song.

If you treated your wife like the song, do you think you’d still be married?

Well, believe me. If my wife got on my nerves like the song, I wouldn’t want to be married to her, no way. Man, can you imagine one song all day Monday through Sunday? Then, Monday again it starts all over. My grandfather had a place that was like a little country juke joint, and he had a juke box in the back, and it was connected to the house so the thing was loud enough to hear that shit all over even out in the yard when it quit playin.’ I’d just run back and press the number for it to play, and there it went again.

Sounds like torture to me.

Yeah, and he’d just walk away. He’d just walk away and disappear. Them old timers want to know where your ass was at all times. Kids nowadays wake up and leave the house before Bozo’s Circus come on, and they come back at night. You couldn’t pull that shit down south.

Sounds to me like this is gonna be a tough gig with Billy Branch.

Ain’t a tough gig. You gotta work to make it interesting. When I play with Billy and Mississippi Heat they want you to play the shit. When you playin’ guitar and all that shit, that’s the first shit you learn how to play. Man, we’re talking about going back to 1965, 1966 for me. That’s a long Goddamn time to be playing that same shit, you know? Ga-donka-donk-adonk-adonk-adonk. What are you gonna do to this to make it interesting? So, you know, I get bored.

I can understand that. That is the same sound they had 50 years ago.

You’re 69 so you remember. You could hear everything you damn wanted on radio stations up in the north, and it really didn’t matter. It wasn’t as specialized as it is now. So when I was growing up, and I came up here, hell, you hear the Temptations, 4 Tops, The Beach Boys. You would hear different shit on the radio, and then there’s these guys that are still stuck in this rut playing ga-donka-donka-donk. Like I don’t wanna hear no goddman Jimmy Reed. What’s wrong with you? I do a lot of the Motown stuff. I had a cousin that was the lead singer for The Spinners. He sang “It’s A Shame.” Name is G. C. Cameron, and I had another cousin, his father was one of the Big Three, Leonard Caston, Sr. His son Leonard Caston, Jr. He wrote and produced songs at Motown. So I had a reason to listen kinda closely to a lotta stuff that’s come out of Motown because I had family members up there, and Baby Doo (Caston) was a piano/guitar player played blues and jazz on piano. And his son was doing the Motown thing. So it was just a natural progression as far as I’m concerned to do some of that stuff, and it’s kinda gratifying sometimes. I played with George Gruntz. He just died I think it’s 2012, or maybe this year, (January 10, 2013), but George was a jazz guy. He’s German born, but he grew up in Switzerland. He had a 21-piece orchestra plus us, and he had ’em playin’ blues for one song for Billy, one song for me, and then they wrote a song for us to play. When I went out on a tour with them, I told George, “If you write down the chords I can play the guitar on this stuff.” I can’t hack being at a concert, going out, doing one song and then come back, do one song in the second set. That’s too much just yo-yoing, man. You know what I mean? You stand around there with your damn Duncan yo-yo and throwing it down. You’re basically wasting time. So George started writing out the cords. Then, some of the other guys in the band who were pretty famous people like Howard Johnson who started the original Saturday Night Live Band, Lew Soloff from Blood, Sweat & Tears, Dave Bergeron used to play Johnny Carson and all those guys. Now these cats they saw that I wanted to at least participate in what was going on, so they would help. “Hey, man, right there why don’t you play a major 13th? Well, a minor 13th you can do this and do that.” So I was always trying to get into what they was doing. They was so far out, that band, that you really couldn’t mess up what they was playin’ ’cause these guys, they were standing on the edge of the worm hole. These mutha fuckers was ready to go into cyberspace at any fuckin’ time. About the end of the tour in China, hell, I was on stage with ’em all night.

How big an influence was your neighbor John Scott on you?

Well, without John Scott I probably wouldn’t have been able to really play the blues. John Scott and my father worked together, but John Scott fronted bands around here. To this day, I’ve never seen a person that played as close to B.B.King as John Scott to this day. John was like the carbon copy of me, but John would play the shit out of the guitar, but he couldn’t play cords, and I was down there with my father he used to have me go to the shop where they worked together, and I asked him if I could play one of his guitars. He had a Firebird, so I was playing that, and this song by War came on, “Slippin’ in The Darkness,” and he heard me playin’ that. He said, “Boy, how you play that song?” I was kind of surprised. I was like, “That’s just a C minor. It’s a blues. It’s a minor blues. It’s damn near the same as ‘I’ll Play the Blues for You.'” He said, “I’ll tell you what. If you teach me –” He didn’t say teach. He said, “If you can learn me how to play that tune, I’ll learn you how to play the blues.” And I showed him. At the end there, there’s a guitar solo there. He said, “Oh, I can play the solo. It’s just the cords I can play.” So I showed him how to do it, and when I go down to the shop he would just start showing me different songs by different blues guys or how to play blues licks, and I remember I put a Jimi Hendrix album down there, The Band of Gypsies.

This guy, John, was in his 40s back in 1970, and he was working on the engine on a car, and John said, “Hey, man, I don’t know what that kind of licks on the guitar make it grovel like that, but that sap sucker’s playing blues.” I said, “He playin’ blues?” He says, “Yeah. I don’t give a damn what his name is. That son bitch playin’ blues.” And he went plugged up his guitar. He had a 355 stereo, and he plugged it up and he started playin’. He was plain’ those licks that Hendrix was playing. I said, “Well, can you show me how to play that?” He said, “Yeah.” And he did. A lot of that stuff was just blues licks and he was – “I showed you that lick the other day.” And he did it slow, and he said. “Now do it fast. You gotta practice so you can get it fast,” but John Scott actually opened my eyes to how close rock and blues was.

So you don’t think if he hadn’t been there that you would have been able to make the jump from jazz to blues?

I wasn’t playin’ jazz. I was playin’ nothing but R&B and that Jimmy Reed type blues back then, but where I just got a guitar and kinda learned on my own, learned from standing back and watching different people. John was the first one to get the light bulb to come on.