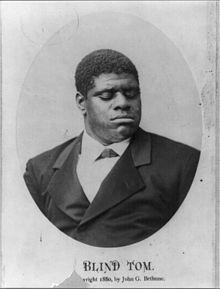

This time in our Behind The Keys series, we’re going to discuss someone you might not have heard of before. Though his music wasn’t really Blues, it was “Blues-ish”, and he is an important, though mostly forgotten, figure in the history of Piano Blues. Blind Tom was one of the 19th century’s most extraordinary performers. A autistic savant with an encyclopedic memory, all-consuming passion for the piano, and mind-boggling capacity to replicate – musically and vocally – any sound he heard, his name was a byword for eccentricity and oddball genius.

Blind Tom was born into slavery in Columbus, Georgia in 1848. His master, Wiley Jones, didn’t want to clothe and feed a disabled ‘runt’; he actually wanted him dead and, if not for cries and pleas of his mother, Charity, Tom would not have lived past his infancy. But when Tom was 9 months old, Wiley Jones put the baby, his two older sisters and parents up for auction, intending to sell the family off individually and not as a unit. The chances of anyone buying blind infant were slim, and his death was as good as certain.

Tom’s life was again spared, thanks to his mother. Not long before the auction, she begged a neighbor, General James Bethune, to save them from the auction block. At first he refused, but on the day of the sale, for reasons unknown, the newspaperman/lawyer showed up at the slave mart and purchased the family. Except for his blindness, Tom was just like any other baby at first, but very soon after arriving at Bethune Farm, things changed and the toddler began to echo the sounds around him. If a rooster crowed, he would actually make the same noise. If a bird sang, he would follow it, or attack his younger brothers and sisters just to hear them scream. If he was left alone in the cabin, he would drag chairs across the floor or bang pans and pots together – do anything just to make a noise.

By the time he was 4, Tom could repeat whole conversations 10 minutes in length, but could only express his own needs in cries and tugs. Unless watched, he would escape: to the chicken coop, woods and finally to the piano inside his master’s house, the sound of each note causing his young body to shake with excitement. After a few of these unwelcome visits, General Bethune finally recognized the stirrings of a young musical prodigy in the raggedy slave child and brought him into the “Big House”, where he was given extensive lessons.

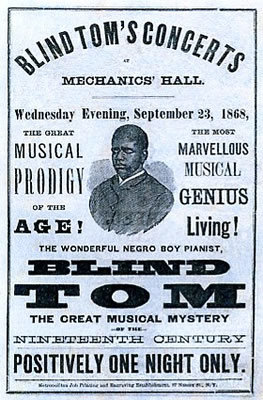

By 6 years old, Tom was performing to sold out houses throughout Georgia. His early managers promoted him as a “untutored, natural musician – fully formed from the moment he first touched the piano.” Tom could repeat any composition, no matter how difficult, after a single hearing.

The actual reality, of course, didn’t really match the showman’s spiel. It was true that Blind Tom had a photographic memory and was astonishingly skillful at imitating, but even at the height of his career, he wasn’t really able to reproduce complex polymorphic concertos after a single hearing. (He would need an entire afternoon to do that, still almost unheard of at any time in history). But if the piece had a recognizable harmony – a polka, waltz, slave song or minstrel hit – Tom could essentially play it when he was 8 years old, and easily nail it by the time he was 16!

When Tom was 8 years old, he was “licensed out” to a traveling showman named Perry Oliver who promoted him as a freak: ‘a gorgon with angel’s wings’. The more animalistic Tom was made to appear (and the newspapers routinely compared him to a baboon, trusty mastiff or hulking bear,) the more amazing the transformation became when he began to play the piano. Before the audience’s very eyes, the incessant rocking and blank open-mouthed expression vanished, and Tom would play the piano with the precision and ease of a master. “I am astounded. I cannot account for it, no one can. No one understands it,” a mystified audience member once said.

The mystery of Tom’s transformation can be explained, to at least some extent, as our understanding of autism has deepened. Autistic people struggle to understand the sensory information bombarding them, and many engage in repetitive behavior to ward off the overload. Tom seemed to have found an escape from this mental overload through music. Behind the piano, the splintering effects of autism (the sensory overload and fragmented perception) disappeared, and Tom was able to experience a sense of integration. These were moments that he clearly savored, and his inspired outpourings of joy impressed the many who witnessed him.

Not long after Abraham Lincoln’s presidential nomination in 1860, Perry Oliver brought Blind Tom to Washington D.C., sensing that something was about to erupt. But the issues that so obsessed his manager – slavery, abolition, secession – meant little to Tom although, ironically, he became a cipher of these times. He was taken to the deeply divided House of Congress to soak up the political vitriol, and over the following weeks, served it up on stage, imitating entire speeches and even debates to audiences roaring with laughter.

Later in the election campaign, Tom was taken to hear the Democrats’ presidential candidate, Senator Stephen Douglas and for years afterwards, performed the rally speech on stage. Tom perfectly captured Douglas’s distinctive boom and somehow, he was even able to imitate Douglas’ physical mannerisms and posture as well — despite being blind. Even more bizarre was Tom’s inclusion of the crowd’s heckles and cheers. “Startling” was how one of Douglas’s supporters described it, despite at least one less-than-accurate slip: “The franatics of the North and the franatics of the South….” Tom’s extraordinary powers of imitation, music and memory also earned him an invitation to the White House, where he performed before President James Buchanan, despite the nation still being in a deeply segregated, slavery-era antebellum time. While the exquisite quality of the executive mansion’s Chickering piano delighted him the most, one significant point eluded both him and the clique of Washington socialites, Blind Tom was the first African-American musician to officially perform in the White House.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Tom enlisted his heart to Confederate cause – or rather that was what his manager claimed, who staged a series of benefit concerts in aid of the Rebel war effort. In fact, Tom was as oblivious to sectional politics as he was to the secretive game that slaves played with their masters; the lip service they paid to their Master’s authority before slipping into the woods to pray for their deliverance. Tom heard not these silent prayers but the crunch of marching feet, rat-a-tat-tat of the drum and fife, boom of musketry and cannon and mayhem of battle. He absorbed these sounds, channeling them into his most famous composition, The Battle of Manassas, when just a lad of fifteen. The sum total of his perfect pitch, hypersensitive clarity, elastic vocal chords, lack of inhibition, and total immersion in the world of sound enabled him to re-create a “harum-scarum” battlefield like no other. White southerners heralded The Battle of Manassas as a work of genius, though black audiences were less overenthusiastic – not really surprising, as Perry Oliver would introduce the piece as Tom’s “spontaneous expression of loyalty to the Confederacy”. However, Oliver’s version of the events loosely plays with the facts. For a start, nine months passed before The Battle of Manassas was first heard in public, which doesn’t really make it a spur-of-the-moment tribute. The wily showman seemed to have used Tom as a propaganda tool to serve his own political agenda.

In the decades following the Civil War, Blind Tom became a household name, celebrated by luminaries like Mark Twain and mid-Western novelist Willa Cather. He played virtuoso pieces to sold out crowds across Europe and America (his tour schedule was relentless,) following them up with unashamedly populist novelties: imitations of trains, banjos and music boxes, playing one piece with his left hand, another with his right while singing a third, then repeating the feat with his back to piano.

At every concert, audience members put his musical memory to the test, and by the time he hit his full virtuosic stride, Tom was virtually unbeatable. As the crowds wildly applauded, he would bound across the stage in a series of spectacular one-footed leaps, howling along with them. The American stage had never seen anything like him.

But Tom’s enormous fame was sullied by the deep-rooted racism of the period. His so-called ‘idiocy’ was continuously confused with the widespread belief that Africans were closer to the animal kingdom than Europeans. But his savant powers also made nonsense of these racist theories. How could a man with gifts like his be an example of ‘the lowest rung of humanity’, ‘a mind dredged of all intelligence and purity’? A century and a half ago, there were few earthly explanations, although several unearthly ones were floating about.

Séances, coquina boards and spectral materializations were all the rage in the late nineteenth century and many saw Tom as a medium, an empty vessel, channeling the genius of the great masters. Years earlier, in his hometown of Columbus, his fellow slaves had reached a similar conclusion: Tom was blessed with the gift of ‘second sight’, and could communicate with spirits from other

worlds. Tom was undoubtedly in communication with something. Many of his compositions were the fruit of a deep and profound dialogue with the natural and mechanical world. He would pass hours rapturously absorbed in a thunderstorm then sit down

at the piano and play “something that the wind and rain said to me.” Tom’s savant powers enabled him to revel in a sonic world alive with vibration and detail. Powered by an almost superhuman capacity to concentrate on details most people would find inconsequential, he could tune into a fantastically intricate world of differentiated repetition: the crank of the butter churn, the drip-drip-drip of water down a drainpipe, the clickety clack of a train or warble of a bird. The bliss he experienced as he drank in these sounds erroneously gave rise to the perception that he was perpetually happy, but after years of social and physical isolation (He was kept locked up alone in a hotel room for hours, day after day) Tom became morose, depressed and suspicious of strangers.

Tom had no concept of money and, not surprisingly, was exploited, deceived, manipulated and robbed blind (pardon the unfortunate irony) by his white masters and guardians. Emancipation failed to deliver him from the shackles of slavery. His master’s son, John Bethune, merely morphed into the role of his guardian and manager. In 1872, Tom was adjudged insane, and the vast sums of money he earned (the equivalent of $5 million dollars today) was squandered on Bethune’s extravagant lifestyle. Then in 1884, Bethune was killed in a railroad accident.

At the time of his death John Bethune was embroiled in a bitter divorce. When his estranged wife, Eliza Bethune, discovered she was cut out of the will, she tracked down Tom’s impoverished mother and persuaded her to move to New York to mount a legal challenge. It took three years of legal wrangling, but in 1887, victory was theirs and ‘The Last American Slave’ – as the press dubbed Tom – was set free.

But Tom’s so-called ‘emancipation’ was little more than a sham. Once Tom’s mother naively handed Tom’s guardianship over to the Bethune’s widow, she was unceremoniously dumped and sent back to Georgia, never to see her son again. Blind Tom’s final years were shrouded in secrecy and paranoia. It was widely believed he died in The Johnstown Flood of 1889, America’s biggest man-made disaster to date. In fact, he was in one of three places: touring the backwaters of North America (his glory days long behind him), holed up in a New York apartment on the lower east side, or listening to the ocean’s roar at Eliza Bethune’s country hideaway in the wilds of New Jersey (purchased at his expense).

In 1903 he made a brief comeback on the vaudeville stage. Tom died of a stroke in 1908 at the age of sixty and was buried in an unmarked grave at Brooklyn’s Evergreen Cemetery. Twenty years later, the daughter of his former master – Fanny Bethune – began efforts to disinter his body into the Bethune family plot in Georgia. A Columbus resident insists he carried out her request as best he could, Jim Crow laws forcing him to re-bury Tom at a nearby plantation. The Evergreen Cemetery, however, insists that the body was never removed. Today, two simple plaques – one in Columbus Georgia, the other in Brooklyn -mark his burial place: a fitting end to the enigma of Blind Tom.

5 Comments

This is an amazing story about someone who overcame incredible odds for his superlative talent to come to the fore. As a music historian and professor of music history (especially Blues and Roots music history) this was fascinating! Thanks for researching and sharing it. Clair DeLune, Blues Moon Radio productions.

What an amazing story of someone who was able to overcome some of the toughest odds imaginable; slavery, blind, autistic… in a time when any one of those things could have easily been a death sentence. More amazing is that he literally did it with nothing more than music.

Fantastic job on this story, Lee.

What an amazing story,, very well-written! Thanks, Lee…..well done indeed.

I relate to Blind Tom.