This heartfelt article was recently a headline on CNN. The story is based in the Mississippi Delta around Moorehead, (“Where Southern Cross the Dog”) and Indianola, (B.B. King’s Hometown).

Moorhead, Mississippi (CNN) – The Mississippi Delta is the kind of place where everyone shows up for a funeral.

It was on such a day in 1997 that Lucas McCarty and his grandfather had come to pay their respects to a young man who’d been killed in a car crash.

John Woods was there to bury his son.

Lucas and John had met a handful of times before, but that’s the day John found his new son and Lucas his “black daddy” – each one delivered in his own way from a tragic past.

John worked for Lucas’ grandfather on his catfish farm as an “oxygen man.” Catfish are fickle creatures, and if they don’t have enough oxygen, the whole lot of them can go belly up in minutes.

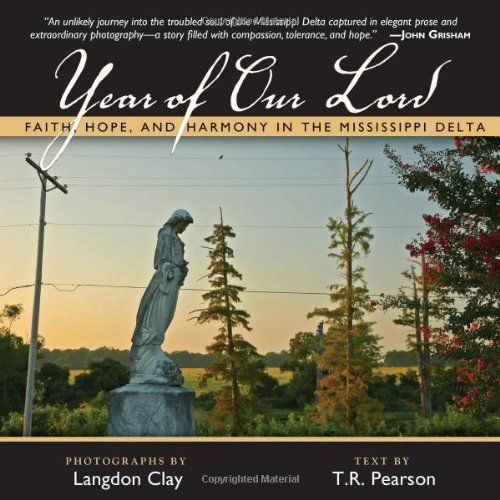

He’d gotten the job a decade earlier after getting out of jail. John had killed his brother-in-law on a lonely Delta road, according to T.R. Pearson’s “Year of Our Lord,” which tells about John and Lucas. John had been indicted and tried for first-degree murder, but the trial resulted in a hung jury. He was then indicted and tried for first-degree manslaughter – and this time the jury found him not guilty. He was a free man.

At about the time John was starting a new life, Lucas’ life was almost ending before it could even begin.

Elizabeth Lear McCarty’s heart sank when her son was born, the familiar cry of a baby’s entrance into the world replaced by phrases like “no heartbeat” and “no spontaneous respiration.”

Elizabeth says a botched delivery deprived her son of oxygen at birth, damaging his brain.

He was born “gray and dead,” she says.

There would be unanswered questions and a lawsuit, and pretty soon it would become clear that Lucas would never be like other kids.

Lucas has cerebral palsy, a condition suffered when a baby’s brain is deprived of oxygen, usually at birth. The condition began to show its devastating effects more and more as he matured.

He never learned to walk, read or write. Even eating was a challenge. It looked like Lucas was destined to spend the rest of his days in a wheelchair, dependent on others for his most basic needs.

Though he has never spoken a word in his life, at age 5 he found a way to say anything he needed to. It would take him years to master it, but the machine he shied away from at first, slowly became his link to his family and the world.

Based on Mayan hieroglyphs, Minspeak allows Lucas to create full sentences by pushing a series of pictures.

If he wants to say the word food, he pushes the picture of an apple. If he wants to say eat, he pushes the picture of an apple followed by the picture of a man running, called the “action man.” If he just wants to say apple, he pushes apple twice.

It can get fairly complex to an outsider. A hamburger, for example, is apple + scale + treasure chest. Somehow, this all makes sense if you’ve never learned to read or write with words.

Lucas grew up going to an Episcopal church, but his mom says he never liked it all that much. He was antsy and easily irritated, and sitting quietly for hours not only was difficult, but practically ran counter to his genetic predisposition.

“His sister kept his hands down the whole time he was at our church,” Elizabeth says.

‘My calling is singing the gospel’

At the funeral for his son, John Woods was touched by the presence of Lucas and his grandfather, James Lear.

“I looked around the church and Mr. Lear was there. Lucas was there. That’s to show you an old black man like me has some dear, sweet white friends,” John says.

Afterward, John began coming to the McCarty house to sing gospel songs with Lucas.

“He really couldn’t do much else,” John says. “We would sing songs like ‘God’s Got It All In Control’ ” – no doubt a message that, at the time, offered equal comfort to both of them.

John asked Elizabeth if he could take Lucas to Easter service at Trinity House of Prayer, where he was the music director. John had been saved at Trinity, and he hoped Lucas could be too.

At that first service, John carried Lucas, and because of John’s position as music director, they sat in the deacon’s box, a spot reserved for congregational royalty.

“The Trinity House of Prayer congregation are such a loving environment of peoples,” John says. “A man can be a sinner, a whiner, (but) when they bring him into Trinity House of Prayer he will feel nothing but pure and genuine love.”

The love Lucas felt most was for the music. He fit right in with the loud expressionism and theatrics, and adored the soulful singing. Trinity changed his image of church.

“Shouting, dancing, falling out and speaking in tongues is real church,” Lucas says through his device.

Trinity House of Prayer is known for its choir. Tucked deep into the fertile soil and God-fearing air of the Mississippi Delta, the church is nestled on a flat, barren landscape, one of hundreds in a region where faith is the answer to poverty and hardship.

The chapel isn’t much to look at – an old gray building surrounded by a graveyard of dilapidated vehicles and rusted-out farm equipment. On the inside, windows are covered in a clear red film, a cheap alternative to stained glass. And on a sunny day, the faded carpet and beautiful wood pews light up with a glow that can feel transcendent.

Most notably, Trinity’s congregation is all black – with one exception. Every Sunday for the past 15 years, Lucas has shown up, sometimes carried, sometimes crawling, but always ready to put his “foot on the devil’s head.”

It’s a bit of a peculiar sight, a white man in a black church, on his knees, wailing indecipherably, but passionately into the microphone in the corner of the choir stand. He knows every word, he just can’t say them, but that sure doesn’t stop him from finding his voice.

“My calling is singing the gospel,” he says.

A warm, cleansing oil

Four months before Lucas was born, John Woods prayed for the first time for as long as he could remember.

The hard crack of the pistol, pulled from his waistband and fired without aim on that balmy Father’s Day in 1987, rang through his head over and over.

John didn’t know if the man he had shot was dead, but he knew he was in trouble. He and his wife, Mary Frances, cried together until a squad car pulled into his driveway and took John away in handcuffs.

According to John, he heard his sister’s husband had beaten her with a pipe, and John wanted to get even. He tracked the man down at a diner to give him a piece of his mind, the gun in his waistband providing punctuation for each cautionary sentence.

But according to John’s description in Pearson’s “Year of our Lord,” his brother-in-law didn’t take too kindly to the threat. He chased John down a road and pulled out a .25 automatic. He got off two shots before the gun jammed, and before John knew it, he’d shot back.

John wouldn’t find out for sure until he was in his cell that the man was dead, but he had felt the life leave his brother-in-law the second he shot him.

It was in the Sunflower County Jail where John found God. As he sat there in a cold cell, a cellmate told him to turn his life over to the Lord.

John’s life had been far from charmed. Plagued by drugs and alcohol, he now found himself sharing a fate suffered by all too many poor black men in the Delta. But on one of those sleepless nights, John prayed, and that’s when he says he felt it.

“It was like a warm oil being poured down from the top of my head, running slowly down my body, and every place it touched it was cleansing me.”

It was when John got out of jail that he says “old Jimmy Lear” took a chance on him, made him his “oxygen man,” always telling John not to worry and “keep moving.”

John would drive around to each pond and put a long stick into the water and check the oxygen levels. The job required him to check the oxygen nearly every hour around the clock, so sleeping was in short spurts spread throughout the day and night.

It was during one of these naps 15 years ago that John had a strange dream. In the dream, Tony, the oldest of his four sons, had crashed his truck, and John was consoling him. John awoke to the phone ringing. It was his wife Mary Frances. Tony had fallen asleep at the wheel coming home from work at 4 a.m.

“God called him home.”

Crawling into the choir stand

Despite being told he’d never be able to walk, Lucas has found his own way, slipping out of his wheelchair and onto the floor at Trinity House of Prayer, where he shuffles around on thick knee pads as if in a state of constant reverence.

Drawn to the music, it was only a matter of time before Lucas crawled up into the choir stand. Not only was Lucas the only white member of the church – and definitely the only member with cerebral palsy – until last year he was also the only man in the all women’s choir. A young man has since joined him.

Trinity’s pastor, Willie B. Knighten, tried to heal Lucas at one of his first services. Lucas says it was the only time he felt uncomfortable at the church.

“I only felt funny when the preacher laid hands on me the first time,” he remembers.

It’s the soft spot within many people that makes them wish Lucas normal, but the hand of God hasn’t taken away his condition.

Still, to nearly everyone who attends Trinity, it’s a small miracle each time Lucas crawls into the choir stand on his own every week to sing. In a small way, he has been healed.

Lucas is a lot like any 25-year-old single man. He likes cars, he loves surfing the web, and the No. 1 thing on his mind at any given time is women. He wants a girlfriend – specifically one, he says, who is “an outgoing sweetheart, who does not smoke, has never had children but wants (them) and is a Republican.”

Lucas’ access to the outside world is a bit limited. Because of his handicap, going anywhere can be an ordeal. He refuses to use a power chair, instead relying on the push of a friend, relative or stranger.

A few days each week, Lucas works at his father’s restaurant in nearby Indianola washing dishes and cleaning. When Lucas was 6 years old, his parents got divorced. It’s no secret that the difficulties of raising an impaired child strained the marriage.

The job gets him out of the house he shares with his mother, something that’s important for a young man whose body is disabled but whose ambition knows no limits. Lucas wants to start his own cleaning company, and during the announcements following a recent service at Trinity House of Prayer, Lucas asks for the microphone, holds it up to his machine and slowly types out the message that if anyone is looking for work, he’s hiring.

Church is the one time a week Lucas knows he can get out of the house, and at Trinity House of Prayer people won’t look away when he comes down the aisle.

“Lucas would be at church every time the door opened if he could,” his mother says. “But we just usually go take him on Sunday. And that’s the most important part of the week for Lucas … getting to church on Sunday.”

Lucas has found other ways to connect. He has an e-mail address and a Facebook account, but for years his favorite hobby has been jumping on the CB radio he keeps in the family room. Most of the truckers know him by now. His handle is “Teddy Bear,” and he starts each interaction the same way: “Is there a pot of coffee on?”

John Woods, now Bishop John Woods, has moved on from Trinity to be the associate pastor of a church down the road. He and Lucas still get together, singing their favorite gospel songs just as they did 15 years ago. Lucas’ favorites are “I’ll Fly Away” and “I’ve Got To Run.” Between songs they talk about life and the Lord.

When John asks Lucas if he’s been saved, he shrugs. Despite the music and the love of Trinity’s congregants, he hasn’t quite made his peace with God. It’s a familiar struggle for many, but when you draw a hand like Lucas’, making sense of it all can be even more challenging.

Lucas may still be on a search for God, but the boy who was born without a breath has found his “oxygen man” – and John has found the son he lost.

When they speak of God, John tells Lucas, “Don’t worry, you’ll find him one day.” But Lucas seems content to find his solace “in the music,” and he’s happy as long as he can convince folks of one thing: “I want people to know I am more than a boy in a wheelchair.”