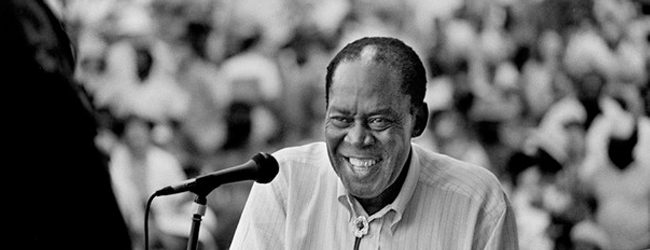

This time in our Behind The Keys series, we’ll take a look at the life of Memphis Slim, a blues man who made a such a lasting international mark on music that most self-respecting music fans can’t go a single day without feeling. Bringing blues piano to the masses and pioneering the popular sound of the blues in it’s 1950’s heyday, Slim’s lifetime of making music is one to be well honored and respected.

Memphis Slim’s birth name was John Len Chatman, and he was born in Memphis, Tennessee. His father Peter Chatman sang, played piano and guitar, and operated juke joints, and it is now commonly believed that Slim took the name to honor his father when he first recorded for Okeh Records in 1940. Although he started performing under the name Memphis Slim later that same year, he continued to publish songs under the name Peter Chatman. Chatman spent most of the 1930s performing in honky-tonks, dance halls, and gambling joints in West Memphis, Arkansas and southeast Missouri. He settled in Chicago in 1939, and began teaming with Big Bill Broonzy in clubs soon afterward. In 1940 and 1941, he recorded two songs for Bluebird Records that became part of his repertoire for decades, “Beer Drinking Woman,” and “Grinder Man Blues.” Both tracks were released under the name “Memphis Slim,” given to him by Bluebird’s producer, Lester Melrose. Slim became a regular session musician for Bluebird, and his piano talents supported established stars such as John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson, Washboard Sam, and Jazz Gillum. Many of Slim’s recordings and performances until the mid-1940s were with guitarist and singer Broonzy, who had recruited Slim to be his piano player after Joshua Altheimer’s death in 1940.

Memphis Slim’s birth name was John Len Chatman, and he was born in Memphis, Tennessee. His father Peter Chatman sang, played piano and guitar, and operated juke joints, and it is now commonly believed that Slim took the name to honor his father when he first recorded for Okeh Records in 1940. Although he started performing under the name Memphis Slim later that same year, he continued to publish songs under the name Peter Chatman. Chatman spent most of the 1930s performing in honky-tonks, dance halls, and gambling joints in West Memphis, Arkansas and southeast Missouri. He settled in Chicago in 1939, and began teaming with Big Bill Broonzy in clubs soon afterward. In 1940 and 1941, he recorded two songs for Bluebird Records that became part of his repertoire for decades, “Beer Drinking Woman,” and “Grinder Man Blues.” Both tracks were released under the name “Memphis Slim,” given to him by Bluebird’s producer, Lester Melrose. Slim became a regular session musician for Bluebird, and his piano talents supported established stars such as John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson, Washboard Sam, and Jazz Gillum. Many of Slim’s recordings and performances until the mid-1940s were with guitarist and singer Broonzy, who had recruited Slim to be his piano player after Joshua Altheimer’s death in 1940.

After World War II, Slim began leading bands that, reflecting the popular appeal of jump-blues, generally included saxophones, bass, drums, and piano. With the decline of blues recording by the majors, Slim worked with the emerging independent labels. Starting in late 1945, he recorded with trios for the small Chicago-based label Hy-Tone. With a lineup of alto saxophone, tenor sax, piano, and string bass (Willie Dixon played the bass on the first session), he signed with the Miracle label in the fall of 1946. One of the numbers recorded at the first session was the ebullient boogie “Rockin’ the House,” from which his band would take its name. Slim and the House Rockers recorded mainly for Miracle through 1949, enjoying commercial success. Among the songs they recorded were “Messin’ Around,” which reached number one on the R&B charts in 1948, and “Harlem Bound.” In 1947, the day after producing a concert by Slim, Broonzy, and Williamson at New York City’s Town Hall, folklorist Alan Lomax brought the three musicians to the Decca studios to record, with Slim on vocal and piano. Lomax presented sections of this recording on BBC radio in the early 1950s as a documentary titled The Art of the Negro, and later released an expanded version as the LP Blues in the Mississippi Night. In 1949, Slim expanded his combo to a quintet by adding a drummer; the group was now spending most of its time on tour, leading to off-contract recording sessions for King in Cincinnati and Peacock in Houston.

One of Slim’s 1947 recordings for Miracle, released in 1949, was originally titled “Nobody Loves Me”. It has become famous as “Every Day I Have the Blues.” The tune was recorded in 1950 by Lowell Fulson , and subsequently by a raft of artists including B. B. King, Elmore James, Ray Charles, Eric Clapton, Natalie Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Jimi Hendrix, Mahalia Jackson, Sarah Vaughan, Carlos Santana, and Lou Rawls. Joe Williams recorded it in 1952 for Checker; his remake from 1956 (included in Count Basie Swings, Joe Williams Sings) was inducted in the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1992. “Every Day I Have the Blues” is also seen in John Mayer’s, Where The Light Is, a DVD (and CD) live recording in Los Angeles’ Nokia Theatre featuring Steve Jordan (drums) and Pino Palladino (bass).

Early in 1950, Miracle succumbed to financial troubles, but its owners regrouped to form the Premium label, and Slim remained on board until the successor company faltered in the summer of 1951. His February 1951 session for Premium saw two changes in the House Rockers’ lineup: Slim started using two tenor saxophones instead of the alto and tenor combination, and he made a trial of adding guitarist Ike Perkins. His last session for Premium kept the two-tenor lineup but dispensed with the guitar. During his time with Premium, Slim first recorded his song “Mother Earth.”

Slim made just one session for King, but the company bought his Hy-Tone sides in 1948 and acquired his Miracle masters after it failed in 1950. He was never a Chess artist, but Leonard Chess bought most of the Premium masters after the failure.

After a year with Mercury Records, Slim signed with United Records in Chicago; the A&R man, Lew Simpkins, knew him from Miracle and Premium. The timing was propitious, because he had just added Matt “Guitar” Murphy to his group. He remained with United through the end of 1954, when the company began to cut back on blues recording.

Slim’s next steady relationship with a record company had to wait until 1958, when he was picked up by Vee-Jay. In 1959 his band, still featuring Matt “Guitar” Murphy, cut LP Memphis Slim at the Gate of the Horn, which featured a lineup of his best known songs, including “Mother Earth,” “Gotta Find My Baby,” “Rockin’ the Blues,” ‘Steppin’ Out,” and “Slim’s Blues.”

Slim first appeared outside the United States in 1960, touring with Willie Dixon, with whom he returned to Europe in 1962 as a featured artist in the first of the series of American Folk Festival concerts organized by Dixon and promoters Horst Lippmann and Fritz Rau. Willie Dixon brought many notable blues artists to Europe in the 1960s and 1970s. The duo released several albums together on Folkways Records, including, Memphis Slim and Willie Dixon at the Village Gate with Pete Seeger, in 1962. That same year, he moved permanently to Paris and his engaging personality and well-honed presentation of playing, singing, and storytelling about the blues secured his position as the most prominent blues artist for nearly three decades. He appeared on television in numerous European countries, acted in several French films and wrote the score for another, and performed regularly in Paris, throughout Europe, and on return visits to the United States. In the last years of his life, he teamed up with respected jazz drummer George Collier. The two toured Europe together and became friends. After Collier died in August 1987, Slim appeared in public very few times.

Two years before his death, Slim was named a Commander in the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of France. In addition, the U.S. Senate honored Slim with the title of Ambassador-at-Large of Good Will.

Memphis Slim died on February 24, 1988, of renal failure in Paris, France, at the age of 72. He is buried at Galilee Memorial Gardens in Memphis, Tennessee.

In 1989, he was posthumously inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame