In a region glutted with flamboyant musicians, James Booker’s reputation as both a genius and a flake reached legendary proportions. On stage he was quite a sight. Wearing a chrome-studded patch over his left eye and donning a funky brocaded military coat or cape, he performed with an improvisational frenzy that made lesser musicians run for cover. A classically trained pianist who was regarded as the equal of such R&B players as Professor Longhair, Tuts Washington, Allen Toussaint, and Jelly Roll Morton, Booker was a major influence on Dr. John and personally tutored Harry Connick Jr.

Booker best described his free-flowing stride piano style as “Spiders on the Keys.” His work with the left-hand was often so dominant that the addition of a bass guitar was superfluous. By contrast, his right hand creations contained seamless classical allusions and jazz-drenched boogie phrases. Yet for all his gifts, the eccentric Booker experienced limited commercial success, and drugs and alcohol blunted his talent before extinguishing his life.

James Carroll Booker III was born in New Orleans on December 17, 1939. His father was a dancer from Bryan, Texas, who decided to change his life’s work by becoming a Baptist minister and relocating to New Orleans. His mother was raised in Mississippi, and she sang with the Baptist church Gospel choir. With such a strong religious influence, it’s not surprising that as a kid, James wanted to become a priest when he grew older. James and his sister Betty Jean were sent to live with a relative in St. Louis while he was still a baby. A child prodigy, he began taking classical instruction on the piano at age six and, according to legend, began to outpace his instructors on the instrument. At the age of 10, he asked his mother for a trumpet. Instead, she purchased a saxophone for him. This didn’t upset the young J.C. (as he was called by his family) as he was still able to teach himself the instrument! That same year, James was hit by a speeding ambulance and dragged for nearly 30 feet. His leg was broken in eight places, and as a result, he would forever walk with a limp. But, even worse, he was given morphine for the pain. This was an early introduction to drugs, which would play a hard role throughout his life. Years later, James would tell his friends that he became hooked on morphine during the recovery process, setting into motion decades of drug dependency. But neither injury nor drugs seemed to affect the youngster’s instrumental brilliance. By 12, he had mastered the piano. He could sit down and play Bach’s three-part inventions, not hammering it like a child but playing it with all the sophistication that would have made Bach proud.

James’ father died in 1953 and he returned to New Orleans, along with his sister, to live with their mother. Enrolled at Xavier Preparatory School, he was classmates with Allen Toussaint and Art Neville. He was a very intelligent student, especially in math, Spanish and music classes. And, while still in school, he put together his first band, Booker Boy and the Rhythmaires, which also included Art Neville.

About the same time, his sister Betty Jean was performing as a Gospel singer at the radio station WMRY every Sunday afternoon. James began to hang out at the studio while his sister was on the air. Soon the station managers discovered that he could play the piano and James became a regular performer himself on a Jazz and Blues show which aired on Saturdays. He was quite impressive, often performing complicated numbers by composers such as Bach and Rachmaninoff. Eventually, the entire Booker Boy and the Rhythmaires became the featured artists on the show. Impressed by the broadcasts, Dave Bartholomew signed the young keyboard ace to Imperial Records in 1954. Billed as “Little Booker,” he released his first single, “Doing the Hambone.” At 14 James was the youngest artist ever to record for the label. The single didn’t sell very well, but Bartholomew did see promise in the young pianist, Especially with his ability to play in the styles of many popular artists of the time. One of Imperial’s biggest stars was Fats Domino, who was constantly in demand for live performances. Bartholomew decided to use Booker in the studio to record the piano tracks for Fats Domino, so when Fats returned home, all the hit-maker needed to do was to lay down the vocal parts. Booker’s talents were also noticed by Paul Gayten, Chess Records’ A&R man and a performer himself. He decided to try his luck with James and scheduled a session for Booker and Art Neville. They were to be billed as Arthur and Booker, but Neville was unable to make the date and was replaced by Arthur Booker (no relation to James). The single “Heavenly Angel” was released, but much like “Hambone”, it didn’t catch on either.

About the same time, his sister Betty Jean was performing as a Gospel singer at the radio station WMRY every Sunday afternoon. James began to hang out at the studio while his sister was on the air. Soon the station managers discovered that he could play the piano and James became a regular performer himself on a Jazz and Blues show which aired on Saturdays. He was quite impressive, often performing complicated numbers by composers such as Bach and Rachmaninoff. Eventually, the entire Booker Boy and the Rhythmaires became the featured artists on the show. Impressed by the broadcasts, Dave Bartholomew signed the young keyboard ace to Imperial Records in 1954. Billed as “Little Booker,” he released his first single, “Doing the Hambone.” At 14 James was the youngest artist ever to record for the label. The single didn’t sell very well, but Bartholomew did see promise in the young pianist, Especially with his ability to play in the styles of many popular artists of the time. One of Imperial’s biggest stars was Fats Domino, who was constantly in demand for live performances. Bartholomew decided to use Booker in the studio to record the piano tracks for Fats Domino, so when Fats returned home, all the hit-maker needed to do was to lay down the vocal parts. Booker’s talents were also noticed by Paul Gayten, Chess Records’ A&R man and a performer himself. He decided to try his luck with James and scheduled a session for Booker and Art Neville. They were to be billed as Arthur and Booker, but Neville was unable to make the date and was replaced by Arthur Booker (no relation to James). The single “Heavenly Angel” was released, but much like “Hambone”, it didn’t catch on either.

Over the next few years, James went on the road, playing with many of the popular bands of the day. Unlike Fats Domino’s constant life on the road, Huey “Piano” Smith did not like to travel at all. Again, because of James’ gift for sounding like other performers, he went on tour throughout the South making appearances as Huey Smith. It was a win-win situation for both of them, and sometimes he even performed local gigs when Smith accidentally double-booked himself. James also did several tours with people like Earl King, Shirley & Lee and Joe Tex.

It was through Joe Tex, Booker was introduced to producer Johnny Vincent, who signed him to a three-year contract with Ace Records. But, the partnership did not last long. Booker had recorded “Teenage Rock” and “Open The Door” for Ace, but still did not receive much fanfare. A third number was recorded and Booker discovered Vincent dubbing it with Joe Tex’s vocals over his own. That was enough for him, and he dissolved their contract based on the grounds that he was under-aged and could not legally sign it for himself. Disenchanted with the recording industry, Booker left New Orleans and enrolled in Baton Rouge’s Southern University in 1960.

Involvement with heavy drugs began to take it’s toll on Booker, so he returned to performing in order to make money to supply his habit. Traveling to Houston, he began working for Don Robey at the Duke/Peacock label . H e recorded an organ-driven instrumental single titled “Gonzo,” named for a character in the film “The Pusher.” The single hit the charts on November 13, 1960, and remained there for 11 weeks, peaking at number 43. Unfortunately, it would be the only time in his career where he would chart as a solo performer.

Throughout the 1960s, James Booker would work with a number of reputed artists on tour and in the studio. Among these were Little Richard, Bobby Bland, Junior Parker, Lloyd Price, Wilson Pickett and B.B. King. He traveled to New York, where he recorded for Atlantic Records with Jerry Wexler, on albums by King Curtis and Aretha Franklin (who included Booker’s own composition, “So Swell When You’re Well”). Wexler also spent time recording James as a solo artist, but these tracks have never been released. During the late 1960s, Booker also worked with his life-long friend, Mac Rebennack, known better as Dr. John. The two had known each other since the 1950s, often working together in Cosimo Matassa’s New Orleans studios with Dave Bartholomew. Booker’s stage presence started becoming more eccentric also, wearing wigs, capes, eye patches and even a glass eye for his missing left orb. The story behind his lost eye varies, depending on who tells it. Some say it was drug-related, but Dr. John claims in his autobiography that Booker lost the eye after pulling a scam on some record producers they’d written arrangements for. Booker had somehow conned the producers into paying for their services three times and was pushing his luck with a fourth attempt. The producers caught on, though, and had Booker beaten up so badly that he lost the eye. Booker was said to comment afterward, “If I lost the other eye, too, then I might be able to play as well as Ray Charles or Art Tatum.” Booker was always a handful for Dr. John. He consistently upstaged the other performers in the band, and was quite open with his homosexuality, often hitting on those assigned to share his room or to bringing men to the room who he picked up on the road, much to the horror of his roommates. Drugs also took their toll on his dependency to make shows. Finally, Dr. John had enough and released Booker, giving him two weeks pay. Dr. John claims that once he left the band, James went to Joe Tex, Fats Domino and Marvin Gaye each, and agreed to take a role in their respective bands. He was given two-weeks advance pay from each, only to run off back to New Orleans.

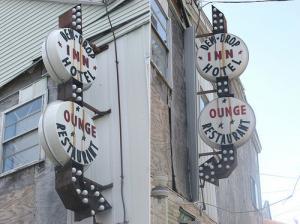

There his life took a drastic change. Outside of the city’s famed Dew Drop Inn, Booker was arrested for possession of heroin and was sentenced to serve two years at Angola Prison. While an inmate, he worked in the prison’s library and also developed a musical program within the system. His efforts paid off, and he was granted parole after only serving six months. When he returned to New Orleans, he found that the music scene had hit a slump and was not very prosperous. Seeking work, he violated his parole by leaving the state and moved to New York, and later Los Angeles, working as a session man on recordings by Ringo Starr, Maria Muldaur, the Doobie Brothers, Charles Brown, and T-Bone Walker. After being cleared of parole violations in 1975, he returned to New Orleans to resume his own recording career. Now singing as well as playing, he scored an immediate critical success with Junco Partner, his first album for the Island Records’ subsidiary Hannibal. Starting out with Booker’s instrumental take on Chopin (‘Black Minuet Waltz’) and rolling through Leadbelly’s ‘Good Night Irene’ sets the listener up for the best of Booker. The title song in Booker’s rendition, is a lyrically disturbing work, touching on the grip of heroin and cocaine on this talented man’s life, summoned by a rolling lefthand bass lines and right-hand filigree. He appeared at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in 1975, where he drew the attention of record scouts. Booker was suddenly regarded as the talented musician that he always had been. He began tutoring a young politician’s son by the name of Harry Connick, Jr., whom Booker saw a resemblance to himself as a child prodigy. The Album Junco Partner, received praise from many critics with its fine showing of Booker’s dexterity, performing music ranging from Chopin to Earl King, alongside his own material (something that came quite easily for Booker, as he often combined classical and modern music in his stage act, as well, often within the same song). This also led to Booker’s traveling to Europe for the first time, to appear in several festivals. His performance at the Boogie Woogie and Ragtime Piano Contest in Zurich, Switzerland was recorded in 1976, and released as New Orleans Piano Wizard: Live! The recording was a triumph for Booker, honored with the Grand Prix de Disque de Jazz award as best live album in 1977. He followed that up with more European shows the next year, including the illustrious Montreux International Jazz Festival.

When Booker returned home, he was a changed man. He no longer adorned the extravagant capes or eye patches, and his mental condition was beginning to fail. He often checked himself into the mental ward at New Orleans’ Charity Hospital. By the 1980s, his shows were becoming more and more erratic. Though he was now a featured performer at the Maple Leaf Bar, working with the astounding team of Johnny Vidacovich on drums, bass player John Singleton, and saxophonist Alvin “Red” Tyler, the shows did not always come across. When they did, Booker was arguably the best the city had ever seen (captured magnificently on the posthumous releases, Resurrection Of The Bayou Maharajah and Spiders On The Keys). But, too often, he would refuse to play, or would walk off-stage mid-set and occasionally even vomited onto his own piano keys. The crowds began to disappear.

Rounder Records decided to record Booker in 1982. The sessions almost seemed doomed before anything even took place. A week prior to the session dates, Booker collapsed in a seizure and was admitted to Charity Hospital. His condition seemed to worsen, and he was transferred to Southern Baptist Hospital where it was determined that his liver had suffered irreparable damage after years of alcohol and drug abuse. Miraculously, he recovered in time to make the recording dates, but the first day he refused to play, the second he appeared unable to, and, on the third, he returned in spirits as if he had never been sick in his life. that day he laid down more than enough tracks for the album that would become Classified. Two days later, Booker disappeared, only to be found several days later jailed for disturbing the peace.

Booker tried to take on a more acceptable lifestyle. He took a job with City Hall as a clerk, typing and filing in 1983. But, he soon began drinking again despite his liver ailment, and lost the job. He still had his Maple Leaf gigs, but he began missing them altogether. The last show he performed there was on October 31, 1983, with only five patrons in attendance. For the next show on November 7th , he didn’t show up at all.

On November 8, 1983, James Booker took a deadly dose of low-grade cocaine and passed out. He was driven to Charity Hospital and left in the emergency waiting room in a wheelchair where he sat undiscovered for nearly a half hour. When he was checked on, he was already dead, having suffered heart and lung failure. He was only 43 years old.

New Orleans is well known for its elaborate funeral processions, especially when it comes to it’s beloved musicians. The funeral for James Carroll Booker III was sparsely attended with very few floral arrangements. He was laid to rest in a family plot at Providence Memorial Park in nearby Metarie, Louisiana. A sad farewell for a musician now honored as one of New Orleans’ true piano geniuses, regarded perhaps only second to Professor Longhair