Recently, American Blues Scene covered the earliest history of the reverb effect, from its existence in specially constructed live performance venues through the implementation of chamber reverb and then plate reverb in studio recordings. The question remains, though, how did this fabulous effect that gives a musician the sound of a giant concert hall become available even when crammed into an enclosure of plywood, wires and knobs no bigger than a lunchbox?

Although personal instrument amplification had existed since the early 30s, it took another thirty years or so for small-scale, readily portable reverb to become available. The first instances of reverb came to the public market in the form of church organs. Hammond began producing an artificial spring reverb for its instruments beginning in the 40s. In the later fifties, the Fisher stereo company began selling a piece of gear that produced what they called “concert hall realism.” It used a separate amp and additional speakers plus a Hammond spring reverb unit to affect a concert hall sound. Fisher’s next step in reverb use caught the interest of folks at Ampeg amplifiers, and they incorporated it into their Echo Twin and Reverberocket models in late 1961 or early 1962, sneaking in just slightly ahead of Fender’s Vibroverb, which is often regarded as the first amp with reverb.

History is fascinating, but American Blues Scene likes to delve a little deeper into the whys and hows of things. So the next question is what is this “spring reverb,” and how does it work? At this point it helps to refer back to Part 1 of our reverb article from last week where we talked about plate reverb. Plate reverb works by transmitting an electronic signal into a large piece of flat metal plate that vibrates and produces the reverb sound. Spring reverb functions on much the same principle — only instead of using a plate it uses a set of springs. A set of springs is mounted on a plate that is isolated from its enclosure by being suspended from a set of tensioned springs. An input transducer creates the signal that is sent into the springs. The springs receive the signal, causing them to vibrate. An output transducer picks up the resulting signal at the opposite end of the springs. The use of multiple springs helps to improve the characteristics of the affect, as each spring is slightly different diameter, wire gauge and length, helping to create a sound one would hear if the instrument’s output was being bounced off of different sorts of surfaces in an actual room.

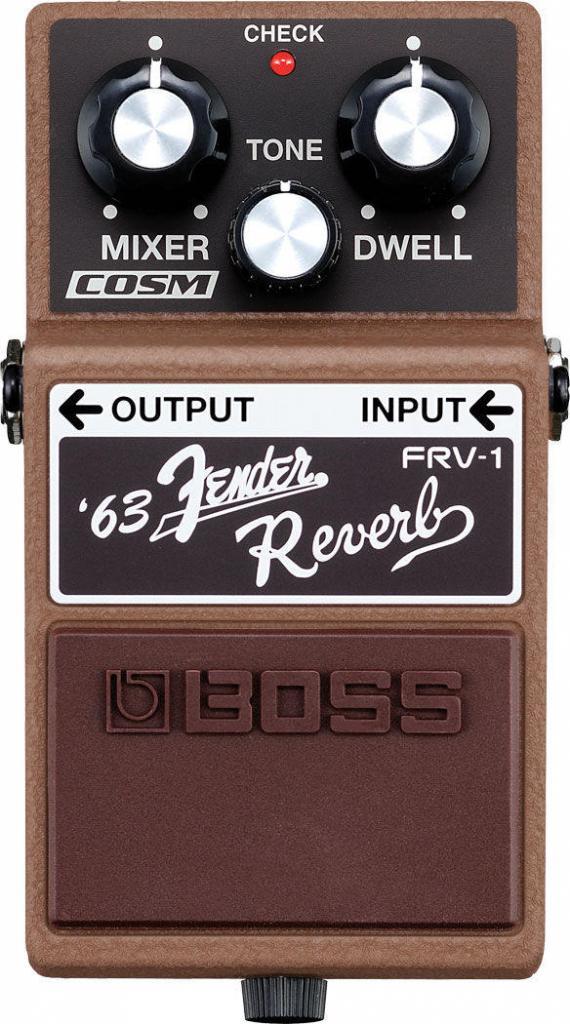

With the advent of spring reverb, the issue of portability was eradicated, and the resulting amps caused musicians aplenty to swoon at the sound. It became the hot new thing to have in guitar gear, and many other manufacturers rushed to add the new technology to their lineups. Reverb units could be had as “tanks,” which were separate, outboard units that could be plugged into the signal path with guitar cords, as well as being onboard affects integral to the amplifier. Spring reverb was the only choice for gigging blues players for a number of years. The first digital reverb did not become available until 1976, again a product of EMT. Digital reverb takes the analog signal and converts it into a digital one, effectively becoming a sampler, using a small recorded portion of the sound and playing it back with the depth and saturation selected by the user. The EMT unit was for studio use only. It wasn’t until 1987 that Roland/Boss produced the RV-2 digital reverb stomp box, making digital reverb readily available to road-going musicians.

These days reverb often comes in several forms. Spring reverb remains popular and can still be purchased new as either an onboard effect or as a separate tank and even as a rack unit. Digital effects are available as rack-mount units or stomp boxes.

Many blues players are and have been fond of the sound of reverb. Magic Sam’s famous “West Side Soul” has reverb all over the guitar, and the “Fire, Fury, Enjoy” sessions of Elmore James are often drenched with it. Walter Horton and Little Walter are two early harmonica players who used reverb to good affect on their recordings. Nick Moss out of Chicago and Junior Watson from California have also been known to add a healthy dose of reverb during their live performances.

For more information regarding all things related to amp gear, consider a look at the book, “Amps! The Other Half of Rock ‘n’ Roll” by Ritchie Fliegler.