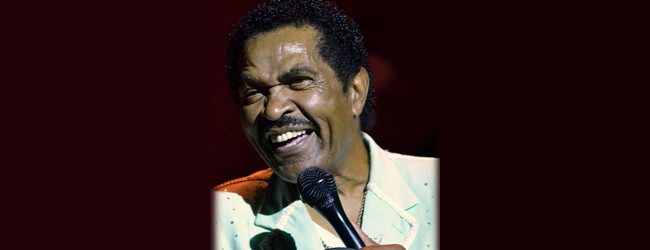

Bobby Rush addressed the hoochie girl’s booty with the intensity of Arnold Palmer preparing for the winning putt at the PGA Open. The young lady with her hands braced on her knees undulated the junk in her trunk in time to the music — shaking her talents like a plastic bag of Jell-O in a tsunami. Bobby leaned forward and brought the microphone closer and closer to her as if expecting her back side to begin reciting The Emancipation Proclamation. He turned his head toward the audience, broke into a crocodile smile, and 10,000 attendees at the King Biscuit Blues Festival hooted and hollered as if they were at a football game and the home team had just scored the winning touchdown.

This is the image most people have of the man known as “the King of the Chitlin Circuit”. At 78 years old, he says he’s recorded 259 records, performed in roadhouses for a hundred people, and New Orleans Jazz Fest for tens of thousands of people. Two years younger than the

late James Brown, he is the country yin to Brown’s yang of urban driving one-chord funk. For almost 60 years Bobby Rush has been dedicated to “crossing over” to a broader audience without “crossing out” his core African American fan base built one by one at back road clubs with a big band based on those of Cab Calloway and Louis Jordan.

His double entendres on originals like “Bow Legged Woman,” “Hen Pecked,” “Wearin’ It Out,” “What’s Good for the Goose Is Good for the Gander,” “One Monkey Don’t Stop No Show,” “Lovin’ a Big Fat Woman” and his 1970s R&B hit “Chicken Heads” are full of double entendres that sometimes become single entendres. “Admit it,” he’ll say leaning toward a guy in the front row. “You’re a sniffer.”

In a field where most of the top performers received little journalistic attention for most of the years Bobby Rush has been performing, he has garnered even less attention. When he has been written up it’s been for his vaudevillian showmanship as the leader of his crack big band. When I saw him do an acoustic set in 2007 on the Legendary Rhythm ‘n Blues Cruise, I was shocked. His guitar playing was delicate, nuanced and reflective of the decades he’d spent playing with masters like Elmore James and hanging with Chicago’s finest beginning in the ’50s. It was but a hint of what was to come.

Bobby Rush’s just released Down in Louisiana showcases another side of a man who deserves being mentioned in the same context as the blues greats Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson, and B. B. King. Writing in Blues Access 15 years ago, Stanley Booth compared Bobby Rush to Dylan as an inspired synthesist with his lyrics. The new album underlines his abilities in this regard. His vocals would fit comfortably with Excello veterans like Slim Harpo and Lazy Lester. His harmonica playing is refined, masterful and as intricate as a full horn section. Produced by his longtime keyboardist Paul Brown in Nashville at Ocean Soul Studios with a core band of four, Down in Louisiana begs the world to re-examine Bobby Rush. He is way more than a caricature, and his marketing savvy concerning how to cross over to a white audience without losing his core African American fan base places him in a unique position among our most serious blues giants today.

Don Wilcock: I was interested in your comments in the press release on Down in Louisiana about how you put this album together. I’m 69, and you’re 77, and I love the fact that people our age are still….

Bobby Rush: I’m 78. So, don’t cheat me. You make me feel good just by calling me, first of all. Let me give you a little insight into where I’m trying to go with this. I was doing this CD because my roots are from Louisiana, but yet this is my 259th record, not CDs, records, through the years and about 70 CDs through the years I’ve recorded. I have 78s, whatever you want to call ’em back in the day.

But I wanted to go back and do this kind of a record because it’s rooted enough to let people know where I came from, but it’s advanced enough for people to understand where I am or where I’m trying to go, and I wanted to do something that is big enough for people to understand I’m a big boy, but I want to sound small enough so I can fit into acoustic stuff so I can save some of the chitlin circuit joints, the juke joints which brought me to were I am now, and most guys in my territory, B. B. King or Buddy Guy, I’m just naming a few guys in that category have forgotten about how we got to where we are now. That was through the juke joints.

Yeah.

And I wanted to do this kind of record so I could fit back into the juke joint circuit and do something economically so people won’t – I won’t burn the bridge the brung me access. So I’ve worked for 100,000 at Jazz Fest in New Orleans. I’ve also worked for juke joints in Tupelo, Arkansas for 150 people. There aren’t that many guys that can work from that angle to the big angle.

What caused you to go to such a big band size back in the ’60s and ’70s when you did because that was pretty brave and economically impossible to do even in those days wasn’t it?

Yeah, but I had the focus and the know-how, and I think I had the showmanship to do that. A lot of guys didn’t have the showmanship. A lot came from Cab Callaway and Louis Jordan who had the small band and yet had the big band sound, and I could do both areas. Where Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf always had the blues thing, they was a smaller band kind of sound, but I came in with the sound of the swing band. I had the small sound but yet was swing band oriented. I sounded like a Gene Krupa kind of a thing with what I was doing, and I went both ways. I wanted to do that so I’d appeal to black radio and black festivals and Broadway like New York. I wanted to appeal to that to get me more work. Sometimes it didn’t and sometimes it did, but nevertheless I learned a lot from it.

I’m interested in how you creatively put Down in Louisiana together. My understanding is that you wrote a lot of the album on guitar and then sat down with (longtime keyboardist) Paul Brown and worked up the arrangements. Is that right?

To be honest with you, Paul Brown was a guy who five years before the CD came out told me, “Bobby Rush, you should consider thinking about Bobby Rush.” I said, “Watcha mean by Bobby Rush?” He said, “Just playing the guitar in the studio, just playing you and being you and let’s build around it.”

That’s exactly what I’ve done. That’s what I did with this CD. I’m to the point where I came in with my arms around my neck with my harp in my hand, with my guitar in my lap, and I just played to Paul Brown who knew me so well so he said, “Hey, if you just play yourself and be yourself, we can make some other things come out of it.”

I started playing to him. He started building things around me. No substitutions, just put musicians around that, and that’s what we came up with. I didn’t want the horns, the whole bit. I wanted the raw sound, a small sound but yet big. And I did the vocal thing. He liked the vocal thing, and I love it, and he kinda convinced me to do it this way which I wanted to do anyway.

I knew at the time when I was doing it just maybe, maybe, maybe I was gonna cross out black radio, but I took my chance because I wanted to cross over to a white audience but not lose my black audience, and that was a hard decision to make.

I remember seeing you on the Legendary Rhythm and Blues Cruise in 2007 when you did an acoustic set just on guitar, and I remember being blown away and thinking that your live show at King Biscuit Blues Festival which I’d seen about 12 times at that point was so flamboyant and so big and so boisterous that I hadn’t really listened closely enough to your guitar work, and now with this album, too, your harmonica work, I think people get lost in the big sound sometimes and don’t recognize how talented you are both on the harmonica and the guitar.

well, I think that’s what happened. You’re so right. It was very well said because people misjudged my ability to do what I do which is to play guitar and harp, and they look at Little Walter and Sonny Boy, but I’m just as (significant) at what I do as Little Walter and Sonny Boy although Sonny Boy was a little bit older, and Little Walter was just a little bit older, but he came up in the same rank in the time that I did. I just happened to be my own self playing both parts as an entertainer, and then he looks at me as a harp player, but I’m a harp player, and I think I’m one of the great ones, and I’ll go down in history as being a great harp player and guitar player. I’m an entertainer also.

I was particularly struck by the way you use the harmonica in the current album. It sounds like a much bigger instrument than most people think of it as. It plays about the same role as a saxophone.

Exactly! Exactly! That’s exactly the way I play harp. I play harp like a rhythm (instrument). My harp is a voice instead of an instrument behind Muddy Waters somewhere. My harp is a lead instrument which is a vocal piece in itself, and that’s the way I play, you know? It’s my style. I think I’ve come to the point where it’s my own thing. It’s the way I play. I think I’m different, but I’m good.

There seem to be fewer double entendres in this album. Did you do this on purpose?

On purpose. See, I’ve done that before, and I did the talk that talk with (my first hit single) “Chicken Heads.” I’ve done that. I wanted to go someplace else. So I kinda pulled it out of the box. So this ain’t nothing new to Bobby Rush, just new to the public which I hadn’t showed to the public this side of me. There’s nothing new to me because I’ve been with me all these years, and I’ve been thinking this in my heart all the time. Now I got a chance. I’ve displaced what’s in my heart. That’s exactly what I did.

What do you think has kept you so vibrant at 78?

Make good music, man. I don’t know. I’m just blessed. I feel I can’t take the blame. I’m smart enough to know that I don’t know anything ’cause when a man tells what he knows he won’t talk long because man don’t know anything, but I do know that I’m so blessed to be enthused. That’s my point to be enthused. I’m still enthused and still learning about this business is what I do, and I’m grateful o the people around me who showed me the way.

I take my hat off to B. B. King, to James Brown, to people like that who came a little bit younger than I, but yet they impressing me a lot and how they challenged themselves. Muddy Waters to Howlin’ Wolf to Lightnin Hopkins, John Lee Hooker, all these people and many, many other people and I feel that young people who enthuse me with what they’re doing now, Prince, people like that. They also enthuse me now by what they do and how they do it. I even like Snoop Dog, not so much as a personality as his music and the way he do what they do in music these days.

When Koko Taylor died, Cookie, her daughter, passed the mantel on to Shemekia Copeland. Do you think when B. B. dies, there’ll be another King of the Blues?

Yeah, but, but, but, you gotta be careful so someone can say it ’cause when someone passes it on down to someone, that don’t mean they earned it either.

I hear ya.

They passed it down because they in a position to pass it down because who is to say who is right? If B. B. say, “I’m the best guitar player in the world,” people seem to believe that ’cause B. B. King said it. That don’t mean that she’s the queen of the blues. If someone passes it down, that’s a broad statement. Who passes down? I don’t think it can be passed down. You got to earn it.

Well, I can’t think of another person outside of B. B. King in our profession who is friendlier and more open and kind to everyone they meet than you are, and I think that’s a big important part of why blues is a kind of music that you can stay in it for decades and people continue to follow it because there’s something about the camaraderie, the friendship in this genre of music that I don’t find in other genres of music.

Well, I appreciate that coming from you making a statement that you think I can walk in B.B. King’s shoes is a great honor to be in that position to do that because I think so much of B. B. where he’s gone. I’m just thanking God that some people think that I’m just not replacement but still of placing me in that category which makes me feel more than I can’t find words to express how grateful I am to be in this position.

Speaking to that issue, what has been the biggest change personally in your life in terms of race relations in the time you’ve been on the bandstand?

Lots! In 1951 I played behind a curtain where people wanted to hear my music, but they didn’t want to see my face, and today I’m talking to you a few days away from having a Governor Award offered to me on the 21st of this month (February) in Mississippi. Close to 60 years ago, I couldn’t stay in a hotel in some parts of Mississippi. They didn’t want me in a hotel. They wanted me playing in front of an audience. They wanted to hear my music playing behind a curtain.

Now I’m getting a governor’s award. How much has changed from that time to this? A lot, but yet the more things have changed, the more they remain the same. I can also see what hasn’t changed, but I can also see what has changed. I’m thankful for the change. I’m sad about what hasn’t changed. Half of the things that haven’t changed will change.

I think that’s what you mean when you talk about crossing over and not crossing out.

Exactly. Exactly! Exactly!! I’m glad we’re talking about that a little bit. You see I’m so blessed. People let me do pretty much what I want to do, and I crossed over and didn’t have to change what I was doing because the same thing I was doing in 1955 in the blues joints, chitlin circuit in the black clubs I do the same thing in the white clubs. They accept me for what I am. I’m not telling you that I haven’t modified some of the things that I have done.

Overall, I really haven’t changed that much, but I’m so thankful I’ve crossed over with a white audience, and I’m wearing two hats. It’s a hard thing for me to wear two hats, but God has blessed me, and I think I’m wearing them well. This record I have now kinda interchanged all these things that I’ve been trying to do, and I’m crossing over. You hear Down in Louisiana. It sounds like the old things, and yet it’s modified for new things.

It’s almost like toilets in the early 1900s. When I was a boy, we had a outside toilet. You had to go outside to a toilet. Didn’t look well, didn’t smell well. Now, they got all fancy toilets. But guess what? We’ve changed how the toilet looks or smells, but the same thing you did in it then, you do in it now. We haven’t changed that. You haven’t changed what you do in it, so I’m saying to you that I have modified and crossed over to a white audience and yet I haven’t crossed out the black audience, and people have accepted me for what I am. What you see is what you get, and I thank God for that. That don’t happen to everybody, but it happened to me, and I thank God for that.

Where did you get the insight into marketing the way that you do because there are very few African American artists from you generation that were able to get up and above the creativity to understand what they had to do to reach a larger market. What gave you that understanding?

I guess because from my father who was a preacher, the pastor of a church. At 12 years old, he asked me to drop out of school to get a job at a gin where they were picking cotton and bailing cotton and what have you, and they was paying me $6 a week. He asked me to get a job at the gin so I could bring the news to him.

Now you got to understand what I’m saying. The news was that we didn’t know anything. As black people we didn’t know anything about what the cotton was selling for. But people inside the gin they would talk about the sales of cotton, the sales of corn, the sales of peanuts, beans, and soy beans, and the prices was around the table, and I wasn’t more than 12 years old. So the people around the table thought I didn’t know what they was talking about.

So I had a rag in my pocket and some sand in the other pocket. I would throw the sand around the guys’ shoes on the table so I had a reason to be at the table to wipe it off. I would hear all the news on what to sell. My daddy would say on Sunday morning. At 10 o’clock he would tell everybody to gather at 9. “Say, boy, what did you hear today?” I said, “Don’t sell no beans, but you can sell the cotton. You can sell this but don’t sell that.” I had all the information to give my father so he could tell the neighborhood people what to sell and what not to sell. I had the price before the price came out.

You know what that sounds like? When I was a youngster, I used to watch the Lone Ranger on television.

Uh-huh.

And Tonto, his Indian companion, would go into town…

[Chuckle]

And he would sit Indian fashion under the bar, and he would hear the bad guys planning their evil duties. Then he’d go back to the Lone Ranger and give him all the insights into what was going to happen.

Exactly. That’s the ending. That’s what I’m talking about. I learned how to maneuver and do my records so I was a black guy who was getting airplay from black radio, and I was playing black music to black peoples, and I knew what black people wanted. So, then I started crossing over to a white audience.

I knew what white people wanted, and what they wanted was good music. So I heard guys say, “I’m gonna record this because I think this is what white people like. I’m gonna record this because I think this is what black people like. I recorded good music and prayin’ everyone liked it because it’s not a black and white issue with me. That’s kind of the way I crossed over.

What was it like working with Gamble and Huff at the contemporary soul label Philadelphia International? (Best known for producing the “Soul Train” theme song for MSFB, Gamble and Huff also worked with the O’ Jays, Harold Melvin and the Blues Notes, Jerry Butler and Wilson Pickett. They produced Bobby Rush’s first album, Rush Hour, in 1979.) My guess would be that you and they were on different sides of the fence.

[Chuckle] I’m glad you mentioned that. When I went with Gamble and Huff they respected me so highly I just loved the men. They were one of the men who put me into the business side of producing, Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, especially Leon Huff. He was so graceful, so friendly to me. He taught me how to produce myself and believe in myself. Here’s what he said to me one time. He said, “Bobby Rush, I’m gonna produce you, but tell me how you want to go.”

Now you have to understand, he’s telling me he wants to produce me, and he asked me how I wanted to go. That’s the respect he had for me ’cause he couldn’t do anything unless he did it for me. I said to myself, “If I have to show him what to do with me, then I know what to do with me.” I’m the boss, and he taught me that I had – he looked at me to do what I wanted to make out of the song, and how I wanted the song to go. I had to style the song.

They would stand and tell me when it’s wrong or right, surely, and I respected them that much, but they respected me so highly and so much that I didn’t know what to do with myself. I had to make sure I was right because if it wasn’t right, the weight was gonna fall on me. And I made sure I was good and I think I showed that.

You should hear sometime my wife and I trying to explain to some of our friends in New York State what one of your shows is like, and nobody gets it until we show them Live at Ground Zero DVD, and they see it and still can’t believe it.

When I went to China, a guy would ask me behind stage, “Bobby Rush, how come the girls go like that?” In other words, how come these Mississippi girls got big booties? How come they grow like that?”

I say, “They grow like that because they eat a lot of rice.”

“You mean to say rice can make them grow like that? If rice makes them grow like that, why my lady’s won’t grow like that? We eat a lot of rice. My woman eats rice every day, and she’s not like that.”

Well, I spent some time in Vietnam, and I gotta tell ya, those women ate a lot of rice, but I never saw them shaking their bootie like your hoochie girls do.

I know it, man. I say that with the purest thoughts in mind just having been with the guys. They wanted to say, “Well, how do they grow it like that?” That’s what they want to say, and I made a joke about it so we would laugh about it, and they’ll just have to call me a dirty old man whatever they want to call me. I can take pride in a dirty old man ’cause you the dirty old man first. I’m the dirty old man second.

“Serious” journalists weren’t taking artists like you seriously 25 or 40 years ago when I started and I did, I guess that’s one of the differences between me and some of my compatriots is that I think we’re only beginning to understand what art really is.

Right.

That it doesn’t have a closed in definition, and that what you do is American. You are an authentic American artist.

I’m so glad you made that statement. I want to say to you that people are just now beginning to take Bobby Rush seriously. When I wrote “Chicken Heads,” my first gold record back in 1969, people thought I was a joke, that I was just guessing at what I do, but if you look at what I’ve done through the years and up to what I’m doing now and the crossover I’m making, you know that I’m not guessing at where I’m going.

I did not get where I’m going. You hear what you hear. If you hear me live, you can almost hear almost literally this thing live because I can duplicate this over and over live with my eyes closed ’cause it’s a natural thing to me. It’s a natural thing, and there are people now who get the real Bobby Rush, and what I’m about if they listen to my name and come to one of my shows. And they cross over. They weren’t sure if I was a bad kind of thing, and I was a hit because of this record was big, and I was gonna fade out the next day or next year. Here I am 59 years later still cutting records and still doing what I’m doing and still learning.

Does it frustrate you that in our business you look at yourself, and you look at B.B., and you look at Buddy Guy, and you look at the late Honeyboy Edwards. Did it frustrate you that you had to get 50 years into the business before people said, “Wow, this guy is an important artist?”

Yeah, it does. It makes me feel bad that you have one leg on the banana peel and one leg in the grave, that most people say, “Hey, this guy (paid his dues) to be here.” I played with Buddy Guy, not in the band with him. So did B. B. When I talk about B. B. and Buddy – and I love those guys – but they don’t have anything to say about Bobby Rush, but they know me.

So I don’t hear that much mentioned, and I (sing the praises of) most of these guys. I don’t mean that much to them as they mean to me, but, sure, they mean a lot to me. I talk about B. B., Buddy Guy and Bobby Bland and all of the guys and some of the older guys. I talk about john Lee Hooker and all the guys before they passed, but I don’t hear them talk that much about Bobby Rush, but they know about me.

I remember when Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf was black entertainers who didn’t have anybody (to listen) but black people listened to them. So did B. B. and I remember those years, and now that they’ve crossed over, they don’t want to talk about (these things the way they was), but I talk about where I was, who means a lot to me, and I take my hat off to all the guys, ’cause B. B. King and all the guys like that made the way for me, and I thank God for that. Maybe I’m making the way for somebody else, but if I have, I want people to know I came this way. I enjoyed this way, and I have people who recognize me that I lived.

Were Freddie King and Luther Allison in your band?

Yeah, Luther Allison played with me. I think I was the first man he was on the bandstand with. I believe I was. I know I was the first one who recorded him. I was the first producer he ever had in his life. He was with me when he first left to sing on his own. Freddie King played with me in 1954 and ’55, off and on, maybe 25 or 30 dates at a certain time over a period of years. Not every night but just some nights. We played a place called Walter’s Corner Roosevelt and Fairfield, Walter’s Corner. I played a lot of little clubs, Checkerboard and a few places like that. A place called the Squeeze Inn and then Elmore James played with me a few times.

You’re often mentioned today in the same breath as Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters. Did you hang with those guys very much?

Oh, man, are you kidding? When I went to Chicago in the early ’50s, Little Walter was there. Muddy Waters was there. Pinetop was there, but he wasn’t playing with Muddy Waters then. Then, Eddie Boyd was there. Willie Dixon was there. Howlin’ Wolf didn’t come until 1957, and Buddy Guy came in 1957 or ’58.

There was a place called Curly’s on (Holman) Ave. and Roosevelt Rd. that Buddy Guy came to. Curly was the guy who owned the place called Curly’s Place, and Buddy Guy got a job there working Friday and Saturday. There was a hole in the left side of the wall. Buddy Guy would play, and he would kick the wall with his shoe. He was known for kicking the wall in. So when the place closed up, there was a hole in the wall that Buddy kicked in.

So he came to Chicago at that time, and then Etta James came up in ’57 and Ralph Bass was working at Chess. There was a black lady at Chess. I was the one who picked her up at the bus station and brought her to Chess. So now out of our Chess group, Chuck Berry and I are the only ones left. There’s a lady in Tennessee. She’s about 80 years old or close to it. Norma, she was the secretary for Chess. Now, she’s still living. So, those are the only three people I know are living. I’m the only one of them. There’s Chuck Berry and the lady in Memphis, Tennessee today. I come up to her maybe once or twice a year. She was 18 years old then when she was working for Chess as a secretary. These are the only three people I know that are living now today that know that.

Change of subject. Carl Gustafson tells me that when you moved to Jackson, Mississippi, you bought a whole block of one street in the city and put all your relatives into houses. Is that true?

No, that’s not true. What I did (was) I bought ’em one at a time. [laugh]. I just came in, got a little house here, and a little house there. Now I just have two houses there with my son living in one, and I had a couple of daughters that passed away years ago and a son, two daughters and a son. So now it’s kind of like the Bobby Rush block, but I didn’t do that to be a big boy. That’s just the way it went.

In the Blues Access article you talk about living with your mother as a child.

Great grandmother, my grandmother and great grandmother from there. My great grandmother was a slave in the house with I believe his name was Vance Spivey. I believe he had five children by his wife – six by my great grandmother. She was a slave in the house with him, a midwife or concubine, whatever you want to call ’em at the time, and when my great grandmother got old enough to travel, the half brother was 19 years old, stole his half sisters and brothers from their mother, took ’em to Arkansas, freed them as slaves.

The reason why we found out later they freed ’em as slaves is because our great great grandfather wanted to buy his land to (give) to his children and because they didn’t want (to buy) the black children, they took them away from their mother. They stole ’em away, took them away. So they had to divide the land equally among the black children, and that’s what happened.

There was one child left who was two or three years old, couldn’t travel, would be my great, great auntie we didn’t know about. So, I’m the only great, great grandchild that came back to Mississippi after close to 100 years because we were told not to come back to Mississippi because we were in harm’s way. We found out it wasn’t in harm’s way, the the kids didn’t want to divide the land that he had on his sick bed divided to his children and my great grandmother was one of them.

Was it tough to make the decision to live in Mississippi?

Oh, yeah. It was a tough decision until I found out the truth because when I found out he was the kind man who wanted to divide his land to his children. He meant well by his children. Slave or not, that’s the story.

I am in awe of you, Bobby. I love the fact that you carry on the tradition. I love the fact that you go forward, but you don’t forget where your roots are, and I love the fact that you’re proof positive that people our age can still be creative and still get excited over our art.

It’s getting to be a dirty old man. It’s getting to be a dirty old man.

Well, I wasn’t going to talk about that.

Let me tell ya that I’m so thankful that I’m still enthused. My mantra is if God keeps me enthused I’m happy because a man can live a long time without water or food but a man cannot get along without hope. As long as I got hope and am enthused, there’s a chance to be creative, and that’s what I do for a living. I’m creative.

You certainly are that, and I’m honored to have spent the time with you today, and keep up the great work.