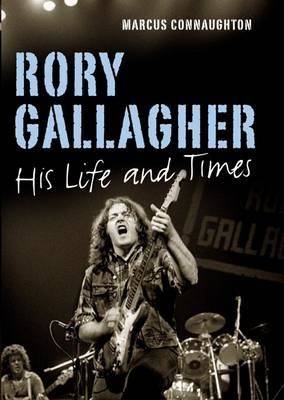

Marcus Connaughton (The Collins Press 2012, Hardcover) 181 pages, indexed and illustrated

One doesn’t think of the Blues and Ireland necessarily in the same sentence. The Blues are supposed to be played by hard men from the Deep South or Chicago, hidden behind shades and with a barrel of whiskey in their guts and the sight of hell in their eyes. Whereas the Irish, in the words of the great sportswriter Barry Glendenning of The Guardian, are seen as wandering from one Theme Pub to another, carrying a pig under one arm. The Irish are either sweet and helpful souls, or drunk and violent bomb-throwers; such are the stereotypes.

And yet, if you find RTE Player on the internet – RTE being the national broadcast network of the Irish Republic – and listen to it from 10PM until dawn, there is an astonishing array of rare Blues music. When was the last time you heard Sonny Boy Williamson, Blind Boy Fuller or even Muddy Waters on mainstream radio, ignoring that 10-11AM timeslot on Sunday that North American radio occasionally tosses the Blues because they figure nobody’s listening and some air is better than dead air? If you don’t live in a major metropolitan market where there are ten or more FM stations, it is doubtful if you ever have heard such music that sent you running to the laptop keyboard so you could madly type, ‘Guess what I just heard!’

And yet Ireland does that; Ireland with a total population of 5 million, a Chicago spread out over an island with plains and hills and farms and scattered little towns. This odd little country ‘gets’ the Blues in a way you would never expect. There is no delta in Ireland, no hot Texas hills, no Chicago ghetto and it is possible to walk a full hour through the streets of Dublin without ever seeing anything other than a white face. So all the cultural definitions we generally apply to the Blues are shot out the window or down the toilet. Why; and more than why, How?

Rory Gallagher was a kid out of the hardscrabble port city of Cork, Ireland who at the age of fifteen in 1963 bought a 1961 Fender Sunburst Stratocaster for £100 (quite a bit then) and with only the slightest of exaggerations basically never put that guitar down until he died of a botched liver operation and subsequent infection in 1995. In between, that kid lived 32 years that puts our own years to shame.

Marcus Connaughton produced the first-ever dedicated Blues show on the aforementioned RTE back in the 1980s and as such got to know Rory and his manager/brother Donal quite well. Connaughton also delivered the first-ever Rory Gallagher Memorial Lecture in Cork after the great guitarist, songwriter and vocalist’s passing. ‘What?’, you are thinking, ‘They do annual lectures for a guitar player?’ Oh my yes. Plus there are dedicated statues to him in Dublin, Cork, Donegal where he spent part of his youth, as well as the Rory Gallagher Memorial Blues Festival held annually in Donegal County which this February was named the best Irish Festival for such events attracting between 10,000-30,000 in audience. That kid and that beat up old guitar had a cultural impact in Ireland equal to that of Sinatra or Elvis in America. And he played the Blues. Imagine that.

Blues records were hard things to come by in the early 60s in Ireland and God knows there was no airplay to speak of save for the occasional song on the famed Radio Caroline, a pirate station based in international waters off the coast of England. Still, and the best of Connaughton’s book is tracing how Rory learned the Blues, Gallagher found the records and in turn honed his craft.

A beautiful thing about Blues musicians is that, whereas a modern pop star might be hard-pressed to name you five Beatles tunes, Blues musicians respect their elders. As such, in wonderfully described episodes, Rory happily lent his skills to London Session Lps by both Muddy Waters and ‘The Killer’ Jerry Lee Lewis. One cannot read about Jerry Lee reaching into a thankfully empty sock for a pistol when taking personal affront against an unintended slight by John Lennon without thinking, ‘Oh wow man, you were the guy who calmed down The Killer!?!’ The other guitarists, oh by the way, on Jerry Lee’s album – likely his best studio album – were Peter Frampton and Albert King. If you listen to it, as you should, the magnificently controlled howl of Rory’s Stratocaster are easily identifiable.

But we were talking about respect. Here is respect for you. From Rory Gallagher: His Life and Times, an excerpt where he discusses how he learned to tune his guitar to play a Leadbelly song:

At present I’m doing numbers like Leadbelly’s “Out on the Western Plain”, where the tuning is D,A,D,G,A,D (low to high). It’s a D tuning, except that the G remains a G. “Out on the Western Plains” was always one of my schoolboy favourites, because of the lyrics. I thought, here’s Leadbelly singing a song about cowboys, and it didn’t seem to be part of the black culture. But as it turns out, there were African-American cowboys. So i was fiddling around with slack D, or whatever they call it, and I found there’s instant unison. If you use a two fret interval on the second and third strings, you can go up like a dulcimer of a sitar. At any point up the neck, if you hit the second string at a certain fret and hit the third string two frets up, then those notes are the same. You get a kind of raga, dulcimer type of thing. So it seemed such a nice idea to do the Leadbelly song in that semi-Celtic-come-whatever style. It’s never quite major or minor, so you can do tricks with it.

Do tricks with it. That paragraph alone may explain why Rory Gallagher turned an unlikely nation onto Blues. He first had the passion to want to hear the music, then the decication to understand the music, and finally the passion and artistry to pay homage to it while equally making it his own.

This book is an exemplary study of passion and single-mindedness. Gallagher had entire studio albums dumped ny Polydor and others because he did not feel they fit his sense of what the sound shoukd be. He hated multi-tracking and studio sweetening; and he was equally impatuent with the gaudy and inflated arena rock shows of Cream or ZZ Top, who he and his variouys bands toured with. No, Rory Gallagher was all about playing live in a close-knit community of sweaty music lovers in a pub or a club.

No wonder Ireland loves him to this day. The biography is a terrific read with great photography throughout.