I’m just gonna come flat out and say it: If you haven’t paid a visit to the Mississippi Delta yet, plan one now to this starkly beautiful, richly musical place.

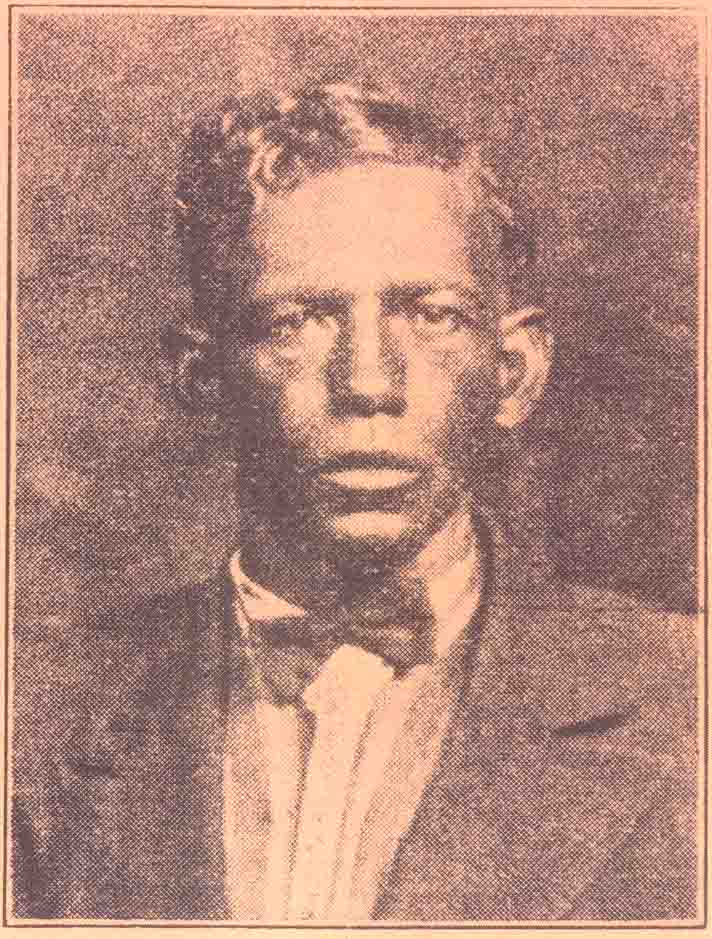

You’ll thank me as you roll down Highway 61, with cotton fields fanning out on either side under an impossibly wide blue sky, following the Mississippi Blues Trail to Robert Johnson’s grave or to Dockery Farms–where the first Delta blues stars, Son House and Charlie Patton, worked and lived. These semi-mythic locations used to be tough for outsiders to find, but since the first Mississippi Blues Trail marker was unveiled six years ago, they’ve been emerging from the mists of time one by one.

You’ll thank me as you roll down Highway 61, with cotton fields fanning out on either side under an impossibly wide blue sky, following the Mississippi Blues Trail to Robert Johnson’s grave or to Dockery Farms–where the first Delta blues stars, Son House and Charlie Patton, worked and lived. These semi-mythic locations used to be tough for outsiders to find, but since the first Mississippi Blues Trail marker was unveiled six years ago, they’ve been emerging from the mists of time one by one.

Down in the Delta, the food is heavenly (especially if you dig real mayonnaise and your vegetables fried), the people are friendly and the music is nonstop and authentic. And this cradle of American rock, jazz and blues needs us to come spread some love and tourist dollars around. Cotton is still king, but it’s no longer picked by hand. Farming has been mechanized, and workers struggle to find employment and the dignity of self-sufficiency.

“How has the recession affected the Delta?” I asked American Blues Scene editor-in-chief Matt Marshall as we tooled down 61 from Memphis airport toward Gateway to the Blues Visitor Center in Tunica MS. Tunica was first stop on the book tour American Blues Scene had arranged for my award-winning blues glossary The Language of the Blues: From Alcorub to Zuzu during Bridging the Blues, a 12-day event connecting Highway 61 Blues Festival and King Biscuit Blues Festival

“Ha! It’s brought the rest of the country a little closer to where the Delta’s always been,” he replied.

Nearly every blues legend I interviewed for my book–like Robert Jr. Lockwood, Hubert Sumlin and “Little Milton” Campbell–grew up here, as did B.B. King, Muddy Waters and more. This birthplace of the blues is a two-hundred-mile leaf-shaped river delta containing some of the world’s most fertile soil. The land is completely flat from Memphis to Vicksburg, bound by the Tallahatchie and Yazoo Rivers to the east, and the Mississippi River to the west. Today, the Delta is covered with cotton and soybean fields, and dotted with little towns.

The river-rich soil was once hidden under dense forests and canebrakes, flooded each spring before man intervened. Cotton farmers began the hard, slow work of clearing the land in 1835, but made little progress. Determined to get back on their feet after the Civil War ended in 1865, farmers redoubled their efforts to build levees and clear the land. Thousands of freed slaves migrated to the Delta, recruited by labor agents promising higher wages and civil rights.

Irish immigrants flocked to the Delta, too. Like black workers, many were forcibly conscripted to work on levee and land-clearing crews. Irish workers were referred to as “white niggers,” and storefront signs in the early 1900s often read “No Blacks, No Irish.”

Building the levees was dirty, dangerous work. Mules and men were killed or injured tumbling down the steep, muddy slopes. Lonnie Johnson’s “Broken Levee Blues,” written after the great flood of 1927, tells the story:

The want me to work on the levee/They’re coming to take me down

I’m scared the levee may break and I might drown

The police run me out from Cairo, all through Arkansas

And they threw me in jail, behind these cold iron bars

They said, “Work, fight or go to jail.” I said, “I ain’t totin’ no sacks.”

I won’t drown on that levee and you ain’t gonna break my back

This intense push created a new economy–and a new society in the Delta among poor blacks and whites. “Prejudice? Yes, there was in some areas but for years and years you had whites and blacks living next door to each other in the same neighborhood, getting along,” polished blues bandleader Milton Campbell, Jr. told me. “They would visit, they would be together, and of course,” he added, laughing, “some of them would sleep together, which you can understand when you see the different shades of skin!”

Campbell was born in 1934 to sharecropper parents in Inverness, MS. Sharecroppers were tenant farmers, working a land plot in exchange for a share of the money the crops brought in when the landowner sold them.

This feudal economy sprang up after the Civil War, when many Southern landowners couldn’t afford to buy seeds and fertilizer, let alone pay workers. Meanwhile, their freed slaves had no work and nowhere to go. Many were still living in slave quarters, or in shacks they’d thrown up, trying to grow enough food in their gardens to survive.

A bargain was struck. Landowners mortgaged their properties to get loans from local banks to buy seeds, plantings, tools, and provisions for their freed slaves. Ex-slaves, in turn, agreed to plant, tend and harvest the crops in exchange for shares.

Because the landowners sold their sharecroppers supplies on credit, though, the owners could set prices and interest rates as they wished. Although some landlords were fair, many overcharged so that, come harvest time, a sharecropper’s earnings after expenses might total zero, or even leave the cropper in debt.

Even so, a picker in the hill country could earn about a quarter a day, but in the Delta he could make a dollar or more a day. Fall cotton pickers often went home, packed up their families, and moved to the Delta to sharecrop year-round. Large plantations like 10,000 acre Dockery Farms hosted as many as 250 families. Owner Will Dockery earned a reputation for treating his croppers fairly that attracted more workers. Today, the family runs Dockery Farms Foundation, chaired by blues and Southern culture scholar William Ferris.

Dockery was home off and on to Charlie Patton, an enormous influence on Howlin’ Wolf and the teenage Robert Johnson, who hung out at Dockery. Patton and his friends Willie Brown and Tommy Johnson played parties, picnics, and fish fries in the tenant quarters. Wolf moved to Dockery in 1929 not only to work, but also to learn from Patton.

By the mid-1920s, a million African Americans were living in Mississippi, with around five hundred thousand concentrated in the Delta. Through hard work and sacrifice, some families freed themselves from sharecropping’s imprisoning cycle of debt. The men took to the rails as “hoe-boys” or hobos, working harvest seasons around the country. Their wives sold chickens, eggs, butter and cheese and worked as maids and laundresses.

Robert Jr. Lockwood was born in 1915 in Turkey Scratch, Arkansas, an African-American community of former croppers. “In the South there was prejudice and it wasn’t too good,” Lockwood told me, “But my people on both sides of my family owned farms and we was on no plantations except our own. Where I came from a whole lot of black people owned their own everything. Everybody in Turkey Scratch had their own property.”

For Lockwood and Hubert Sumlin, born in Greenwood MS in 1931, the Delta was a musical melting pot. “Down in my part of Mississippi, there were musicians everywhere,” Sumlin said, “We had people down there they speak French, French Creole. We had black Seminole. We had people from Jamaica, the Bahamas. Oh yes, you could hear the African feeling in the songs, in the dance, the way they tapped their feet, in everything.”

Country music and Irish folk-songs influenced the blues, too. “Back then you worked every day,” recalled Campbell, Jr. “And you keep saying ‘blues,’ but you know, it was music, period, that was around everywhere. I was exposed to country and western first. It was the grand Ol’ Opry on the radio for me. I got a chance to listen to people like Eddy Arnold, one of my favorite singers, and George Morgan. I never was into the bluegrass stuff, but I always liked the great stories that the real slow singers would tell.

“They say that so-called twelve-bar stuff is the black man’s blues and country western of that day was the white man’s blues,” Campbell mused, “but I tell you there’s a very thin line between the two musics. Only difference is the beat, and the bars to some extent, but the stories of happiness, sadness, being lonesome, and what have you. All of that was the same.”

Today, passionate blues fans and entrepreneurs hope blues tourism can make an emotional and economic rescue of this culturally significant region that is still the poorest in our nation. I was in the Delta during Bridging the Blues – a two-week fall bonanza of blues festivals, club gigs, jam sessions, street parties and tours crossing three states and anchored by the Highway 61 Blues Festival in Leland MS and the King Biscuit Blues Festival in Helena, Arkansas, Everywhere I went on my week-long book tour (arranged by American Blues Scene) I encountered tremendous positivity from whites and blacks working together to make this happen.

Small businesses like Ohio transplant Roger Stolle’s charming Cat Head Delta Blues & Folk Art gallery in Clarksdale and Po’ Monkey’s Juke outside Merigold–one of the few authentic jukes left and a 2009 Mississippi Blues Trail marker recipient–benefit from the trickle of blues tourists year round and the flood come summer festival season. I met African-Americans with masters and PhDs who have carried their expertise here to help spearhead a Delta Renaissance.

Like C. Sade Turnipseed, who opened da’ House of Khafre culture center in Indianola in 2010. She proudly showed me a model of her pet project: the Cotton Pickers of America Monument and Sharecroppers Interpretive Center. “We want to celebrate and remember the sweat equity our ancestors invested in the cotton fields of the Mississippi Delta, which the United States of America was built upon,” Turnipseed explained. “Every person who benefits from the great American success story needs to say, ‘Thank You’ to those people who worked tirelessly from ‘kin-to-k’aint’ in the cotton fields.” A ground-breaking for the center was held in October in Mound Bayou, MS.

Maya Angelou has signed on as Khafre Inc.’s honorary chair, and superstars like B.B. King, Robert Plant and Morgan Freeman have contributed big chunks of wealth and time to the cause. King has contributed both to help build the sleek $14 million B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center, which conjoins the 1920s cotton gin in Indianola where King worked as a teenager. He returns every year for the B.B. King Homecoming Concert.

Plant, who visits the region regularly, drew the largest crowd in Clarksdale history–over 20,000 people and their wallets–when he brought his Sensational Space Shifters to the Sunflower River Blues and Gospel Festival last August. Freeman opened Ground Zero Blues Club in downtown Clarksdale, which hosts hot regional talents like gospel-tinged singer/songwriter David Dunavent or the fiery Cedric Burnside Project, led by North Mississippi blues legend R.L. Burnside’s grandson. In 2005, Freeman told the Washington Post, “One reason to be back here is because I made a lot of money and I am going to spend it somewhere. This is the best place to spend it.”

Everywhere I went I ran into European tourists who were thrilled to be on the Blues Trail. Yet, I also heard repeatedly, “Americans don’t seem to value this incredible history in their own backyard. Yet I also heard repeatedly, “The locals don’t quite get it yet. A lot of them don’t see how they could participate and benefit.”

This is not unique to the Delta. Business can seem an impenetrable mystery if you don’t learn it at the dinner table, from an enterprising relative, or in school. I’d love to see the Network for Teaching Entrepreneurship (NFTE), which teaches at-risk youth to create and operate small businesses, brings its programs to the Delta. Entrepreneurship education has helped many city kids expand their options beyond welfare or drug dealing, and might prevent some of the senseless crime that plagues the Delta, like the mugging of a 77-year-old white woman last summer in Clarksdale by a black 14-year-old who beat her with a brick in front of her home for her debit card.

Despite these problems, I felt more at home in the Delta than I have since leaving my beloved Chicago blues scene behind for New York City when I was barely out of my teens myself. New York has a lot of things, but falls a bit short on that down-home blues feeling. I surreptitiously brushed away a few happy tears as I watched 77-year-old Bobby Rush and his bodacious dancers playfully work the crowd at Club Ebony in Indianola like we were all best friends. (“Bobby Rush Thrills Intimate Crowd at Club Ebony”) Before the show, Matt Marshall and I were ushered backstage by B.B. King Museum executive director Dion Brown, one of the warmest people I’ve ever met (funny, they all seem to live in the Delta).

Rush, a Grammy-nominated artist and huge star around these parts, was charming and down to earth, as were his sweet dancers. As Matt talked with Bobby, I admired Mizz Lowe’s outstanding collection of high-heeled shoes and she showed me how she keeps them scuff-free in Crown Royale bags. (Keep an ear out for Rush’s new album, Down in Louisiana, slated to be released Feb. 19, 2012.)

I came home wondering why I’d never been to the Delta before. I also came away with questions, so for answers I went to some of the high-powered folks I met. Here are their eloquent answers:

Q: What does the Delta offer culturally that no other place on earth does?

Matt Marshall, editor-in-chief American Blues Scene: They say the Delta starts in Memphis and ends in Vicksburg. From within those borders has come nearly everything we know and love about music in this country. From Muddy Waters to Elvis Presley, and even Levon Helm and Conway Twitty from the Arkansas side of the Delta, this impoverished stretch of flat land gave our entire country a voice. There, music isn’t just on the radio; it’s still a way of life deeply embedded into the area’s unique southern charm.

Steve LaVere, music historian, producer, owner Delta Haze Jazz-n-Blues Tees: A gateway to the heart of American Music at large and American Culture in general.

Wesley Smith, Executive Director, Greenville-Washington County Convention & Visitors Bureau: Authenticity everywhere.

Roger Stolle, owner Cat Head Delta Blues & Folk Art and documentary filmmaker: The beauty of the modern Mississippi Delta is that because it still exists in such a vacuum, and each town seems to keep itself in a silo, the blues music here is still far from homogenized. We have enough living fossils playing the blues that you can still hear distinct regional styles within the state–from the Delta to the Hill Country.

There are younger musicians coming up, but they have access to professional lessons and today’s popular music forms. To hear one-of-a-kind, they-broke-the-mold, real-deal Delta bluesmen, people need to drop what they’re doing and come on down.

Q: Mississippi has the most people living below the poverty line (21% in 2011) of any state in the U.S. Can blues tourism help?

Matt Marshall, American Blues Scene: The Delta has always been known for three things: cotton, the blues, and incredible poverty. In the hundred years since this reputation developed, things have gotten worse–not better. Cotton jobs dried up as its processing was automated, and other industrial jobs have moved on.

Blues tourism has become one of the area’s biggest exports. State and local tourism commissions, and a handful of Delta residents, have done a fantastic job of realizing this early and working hard to promote it.

More people every year are making not just vacations, but pilgrimages to the area. Fans get to pay homage and enjoy the music, the people and the incredible culture, while their tourism dollars help keep area musicians employed, hotels filled, and create jobs. It doesn’t hurt that blues fans lead a wildly passionate and vocal–not to mention successful–impromptu grass roots movement.

The music moves everyone, and the residents treat their guests like they’ve just come home.

Wesley Smith, Greenville-Washington County Convention & Visitors Bureau: I think blues tourism can be a piece of the puzzle. The thing that will make the biggest difference, however, is education. We have to have strong schools.

Roger Stolle, Cat Head: I have never lived in such a welfare state. Both the poverty and the contrast between the “haves” and “have nots” really are stark. Without blues/cultural tourism, authentic blues venues such as Red’s Lounge in Clarksdale, profiled in my and Jeff Konkel’s new film We Juke Up in Here!, would have probably had to drop live music from the schedule. Fortunately, as his older, traditional, African-American customer base has thinned with age, it’s been supplemented with visiting (mostly white, often international) fans. The juke joint experience there is still like stepping into the pages of a history book. Places like Red’s provide more than just music; they provide a glimpse into the culture that created the blues.

Q: I saw African Americans and whites working together at top administrative levels of museums and tourist sites, yet I’ve read charges that blues tourism is “whitewashing” the blues, Southern racism and African American history. How do you respond?

Jim O’Neal, Research Director, Mississippi Blues Trail: An important element in the promotion and documentation of blues on the Mississippi Blues Trail, which now has 167 markers in place, has been the public acknowledgment of the troubled racial history of Mississippi. This topic has been addressed directly in the texts of a number of markers.

The Mississippi Blues Trail is a state-sponsored program. Scott Barretta and I have written the texts, and we have never been censored by any state authorities. At the dedication of the Otis Rush marker in Philadelphia MS, a town notorious for the 1964 murders of three civil rights activists, the mayor–an older white man–said the marker signifies a “healing process” between the races.

There is no doubt that in some places, more outside of Mississippi than in the state, the cultural and racial background of the blues, its crucial roots in African American history, and its continuation as an African American expression have been “whitewashed,” but that’s another topic.

Matt Marshall, American Blues Scene: The history of the blues, while not always appreciated or widely acknowledged, is one of this country’s most important cultural messages. Walking down the streets, ghosts of Jim Crow can still be seen. It was these atrocities and more committed against African Americans in the Delta that made the music what it was.

It’s ironic that many of the blues musicians who are now so highly revered sang about the problems in the Delta, and the overwhelming challenges they faced. Many bluesmen who could leave for greener pastures did. Decades later, people are coming back to the Delta and appreciating the music. Is that a bad thing? How could it be? Every week, busloads of reverent fans spend their hard-earned dollars enjoying the music, cuisine, and culture, helping to preserve the history and messages that came from the Delta.

Wesley Smith, Greenville-Washington County Convention & Visitors Bureau: What the Delta needs most is more dollars flowing into its economy. You don’t market to all audiences the same way and that should be acknowledged. William Faulkner said, “To understand the world you must first understand a place like Mississippi.” The chain of events that led to the creation of blues music is so complicated and so emotional that it is impossible to interpret comprehensively through, say, a magazine ad or a website. It’s a story too big to encapsulate.

Once people are here, however, our “on the ground” presentation should be the truth laid bare for all to see. What created the diamonds of the Delta–black and white–its famed musicians, artists, leaders, writers and activist, was the heat of racial tension, the pressure of coming to terms with it, and the passage of time to give it perspective. To attempt to soften hard truths by “whitewashing” history is counterproductive to the whole effort.

Another important aspect of this discussion is how to make sure the African American community in the Delta sees real benefits from the promotion to tourists of blues and blues culture. There are huge benefits through increased tax revenue to the public as a whole, but we would all like to see benefits less abstract and more direct, such as jobs and entrepreneurial opportunities.

Steve LaVere, Delta Haze: Just like the Blues itself, the Delta is undergoing a cross-culturalization that is inevitable if it is going to survive at all.

Roger Stolle, Cat Head: It’s a tough subject. I may well be “part of the problem,” if indeed there is a problem. I moved from the North to the Delta specifically to “organize and promote from within,” because I saw so few other people doing it — white or black.

When I moved to Clarksdale, a bit over a decade ago, we had twice as many bluesmen alive and probably four times the number of juke joints. Still, because there was zero promotion, there was only reliable live blues two nights a week, and even then, it was hard to find out about it in advance.

Today, we have live blues seven nights a week in Clarksdale, with listings on the Mississippi Blues Trail calendar and the Delta Blues Event Calendar. We have national promotion on Sirius-XM Bluesville radio and a bi-monthly Blues Revue column. Does this mean you’ll see more white folks at blues clubs, juke joints and festivals? Yes. Does it mean that you can still have an authentic, culturally relevant Mississippi blues experience? Absolutely.

The burden of history is very real here, but as your question infers, today’s relatively successful blues tourism scene is the result of whites and blacks working together. That simply wasn’t a reality in the past. It is today. I think that is progress and good for everyone.

Q: What do you personally love most about the Delta?

Matt Marshall, American Blues Scene: There’s history in the land…and it still sings.

Steve LaVere, Delta Haze: That this is the place that gave birth to the Blues. This is where all the stomping grounds of the great bluesmen are, as well as the scenes of Civil War battles.

Wesley Smith, Greenville-Washington County Convention & Visitors Bureau: My favorite memories over the years are the impromptu musical gatherings. People here love music and if you gather five or more for any length of time, the guitars will come out.

Roger Stolle, Cat Head: The blues made me visit, but the people made me stay. Southern hospitality is a very real thing here. When you walk down the street, locals will say hello to you–and mean it.

My favorite area blues musicians include Robert “Wolfman” Belfour, R.L. Boyce, L.C. Ulmer, Robert “Bilbo” Walker, Anthony “Big A” Sherrod, Terry “Big T” Williams, Terry “Harmonica” Bean, Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, Louis “Gearshifter” Youngblood, Elmo Williams, Hezekiah Early, Robert “Lil’ Poochie” Watson, Pat Thomas, Eddie Cusic, Little Joe Ayers, James “Super Chikan” Johnson, Big George Brock, James “T-Model” Ford and some younger artists like All Night Long Blues Band. If y’all find any of the names above listed on my Music Calendar, you must go. Really.

Q: I ran into many European tourists on my trip–why should Americans also value and visit the Delta?

Matt Marshall, American Blues Scene: No other music, literally in history, has made so much of a cultural impact on the entire world. Europeans appreciate it. God only knows why more Americans don’t.

Wesley Smith, Greenville-Washington County Convention & Visitors Bureau: The Europeans are easier to spot because of the accents, but Americans flock to the Delta by the thousands and this grows each year as our tourism efforts become more organized.

All of us have a soundtrack to our life both individually and as a country. Each generation’s music builds on the last, and all of that music traces a direct path back to the Mississippi Delta. Therefore all Americans value the Delta. Many just don’t know it. Yet.

Roger Stolle, Cat Head: During Juke Joint Festival last April, we had international visitors from at least twenty-three countries! Crazy, really, for a little town of 19,000 in the poor Mississippi Delta. We also had national visitors from at least forty-six states.

When I lived in St. Louis, I used to tell folks that it’s only a six-hour drive, but it’s like you flew six hours. It’s a foreign land…so close to home. This is a land trapped in time. The music here still reaches back to the beginnings of the genre. A night in a Mississippi juke joint hearing a seventy-year-old bluesman play and sing will change any fan of music or history forever. But because you can still experience this archaic art form today, doesn’t mean that you’ll be able to tomorrow. C’mon on down to the Delta, and see for yourself.

Buy The Language of the Blues: From Alcorub to Zuzu by Debra Devi

Read weekly excerpts from The Language of the Blues on American Blues Scene

Trailer for We Juke Up In Here