Is there a Memphis sound? Brad Webb thinks so. He’s been totally immersed in the Memphis scene for more than 40 years. “I picked up the guitar of this guy from Atlanta I was doing sessions with and hit one lick, and that guy goes, ‘Oh, man, did you hear that?’ I was like, ‘Hear what?’ And it was me hitting a note, either bending a note or whatever. It was like that guy from Atlanta who was a horn player/keyboard player immediately picked up on the idea, ‘This guy plays different than we do.’ I mean I know we do something.”

Is there a Memphis sound? Brad Webb thinks so. He’s been totally immersed in the Memphis scene for more than 40 years. “I picked up the guitar of this guy from Atlanta I was doing sessions with and hit one lick, and that guy goes, ‘Oh, man, did you hear that?’ I was like, ‘Hear what?’ And it was me hitting a note, either bending a note or whatever. It was like that guy from Atlanta who was a horn player/keyboard player immediately picked up on the idea, ‘This guy plays different than we do.’ I mean I know we do something.”

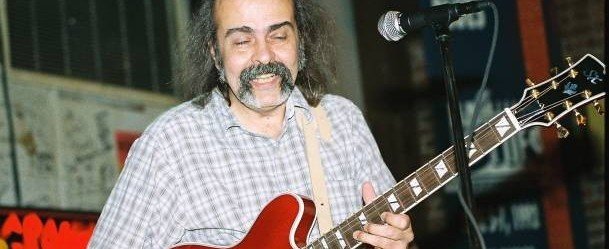

Brad Webb was the guy that stuck in my head the first year I came to the King Biscuit Blues Festival back in the ’90s. He was playing with Blind Mississippi Morris, and he added just enough spin on slide guitar to Morris’ traditional Delta style vocals and harp playing to give it an edge that said he respected rock and roll, but that his heart was in the blues. He was somebody I’ve wanted on the Call and Response Symposium at the King Biscuit Blues Festival since we started it two years ago, and even though he’s not playing with Morris at the festival this year, I still asked him to be on the symposium on Saturday, October 12 at noon in the Malco Theater in Helena.

A true Renaissance man of the blues, he’s a producer with his own studio, a songwriter for most of the artists he produces including Fred Sanders, Robert “Nighthawk” Tooms, the late Willie Foster, and Blind Mississippi Morris. He’s also a player of just about any instrument with strings. Plus he’s rubbed shoulders with real deal blues veterans, some of them famous, some of them not so famous. He recalls hanging out with Louisiana Red at a festival once. They were in Webb’s room jamming with a little cigarette pack amp.

“He was like, ‘How do you do that Albert King or how do you do that B. B. King vibrato?’

“I’m like, ‘Well, I’ll show you.’

“And I showed hi this technique, and I could hear Louisiana Red practicing because my room was right across from his. I mean he practiced that damn technique it seemed like all night, at least for two or three hours. The next morning I’m opening up my door, and here’s Louisiana Red coming back from breakfast going, ‘I got it, Brad. I got it!’

“I said, ‘Yeah, I heard ya. I heard ya practicing. I know you got it.’

“But that’s a perfect case of you never get too old to learn something, and I mean an old guy like Louisiana Red, he had that sparkle in his eye. And he’d picked up on something, and I’m sure what it was, he did it differently, his vibrato, you know shaking the note. We all do it, what we want to hear in our head or in our ear.”

Webb spent more than 20 years as a guitar teacher. He offered his students lessons he’d learned from people like Willie Foster, a legless vocalist who wore his harps like a gun belt and performed up until the day he died. Brad has produced two albums on Willie, My Inspiration and Live at Airport Grocery. He recalls a night he sat in with Willie and a hot shot kid at Airport Grocery in Cleveland, Mississippi.

“I already knew this kid was too loud for Willie. Willie’s in a wheel chair. He’s sitting down at guitar amp volume where the guitar amp is just hittin’ him upside the head, and I played bass ’cause I knew Willie’s stuff, and I knew young people have a lot of energy. Lotta times they keep speeding up grooves and we got through, and we’re outside, and the guy leans over to Willie and goes, ‘Well, what do you think of my playing?’ And Willie goes, ‘Well, you plays alright, but all you hear is you.’ And if that wasn’t a lesson for that young fella, I don’t know what was.”

Webb learned his own lessons in the school of hard knocks, the son of a poor single mom who spent a third of her salary to buy him his first Strat. “It was used and cost about $160. It was serious. They took my Silvertone for a trade-in. I mean that Silvertone wasn’t but 38 bucks new, and they took it on trade, and my mom put a little money with it, and she paid I think it was 12 bucks a month for a year for that Strat.”

Brad ended up in the Naval Reserve and was in the final week of boot camp when they ended the draft. “When I was in boot camp I was sitting there thinking, ‘Man, if I ever get out of this shit, I’m gonna play my fuckin’ guitar, and I’m gonna learn my instrument to where I can change as music changes.’ When I got out (at 20) I took theory and composition. I went to Memphis State for about a year. There were 15 of us. I was one of four that passed through that first semester.”

But his real education came on Beale Street. He started playing with Blind Mississippi Morris there in 1987. “I was playin’ in some copy band, and I’d go play blues with Morris in the park, but Joe Severn would come by and get everyone’s first tip bucket to go to the Blues Foundation. We thought that was a little strange, but at the same time we thought it was going for the right purpose ’cause I mean there was the Blues Foundation in this little bitty house not getting much attention.

“Uncle Ben used to come down there. He was one of the first ones from the old folks home. He had a grocery cart, mike stand and he had a little AC cord, and he could just push that grocery cart out to where there was some electricity and plug it up. He had a little drum machine in there and put up a microphone and, boom, he was playin’. Instead of a flatbed truck with the whole band on it, it was a damn grocery cart, and here is this old guy. He looked like Cab Calloway, and he always had that little body movement. He always had that smile on his face. I mean (Robert) Nighthawk (Tooms) played with him.

“One time he broke a string. I think Billy Gibbons (of ZZ Top) was over at Alfred’s eating. But Gibbons went out to his trunk and got a guitar out. It was called a Cayote, and he kinda had a Bo Diddley style, and he gave it to Uncle Ben. Even Billy Gibbons saw the need. Gibbons has been coming here. His first record he did was at Ardent Studio here in Memphis.”

My favorite album of Brad’s with Blind Mississippi Morris is Walk with Me. You can hear the influence of Duane Allman in Brad’s playing, and his vocals on two of the numbers remind me of early Canned Heat. But there is also a deep respect for Morris’ harp playing and his vocals, too. The package as a whole has the same kind of reverence for blues that Delanie and Bonnie had with just enough edge to kick that Delta style into overdrive.

Blind Mississippi Morris is just a few years older than Brad, but his background in the blues is deeper. Brad says Morris can remember hearing Sonny Boy Williamson at backyard parties as a child. “They’d run the little kids off to bed probably 9 or 10 o’clock, but all that did was make him want to play as a kid, and of course, nobody ever taught him anything. He had to do it all by himself, but sometimes it doesn’t take much for a little kid to want to learn how to do that.”

Then there’s the Howlin’ Wolf connection. “Wolf’s mama lived next door to Morris. Morris was about five or six. Wolf would come home. His mom didn’t like that. Morris says she was sanctified, and he would come home trying to make things easier for his mama with cash, but he said Wolf would have a roll of nickels and would give all the little kids a nickel to go buy candy with. And Morris was one of those kids.”

Brad has mixed emotions about the state of blues from his perspective as a Renaissance man of Beale St. “It seems like the family has gotten bigger, but there aren’t as many plates at the table.” He sees himself as one of the cooks in a kitchen. “Everybody is trying to find a little different spice to put on these things where they stand out.”