The son of legendary Delta bluesman Robert Johnson can keep profits from the only two known photographs of his father, the Mississippi Supreme Court ruled Thursday.

The case turned on a technicality. The court ruled other family members knew as early as 1990 about the photos and royalty payments. A court declared the son, Claud Johnson, the musician’s sole heir in 1998.

Under Mississippi’s statute of limitation, the state Supreme Court ruled a legal challenge should have been filed no later than 1994. A lawsuit by other family members over the photos was filed in 2000.

The court rejected arguments that the clock started when Claud Johnson was named sole heir.

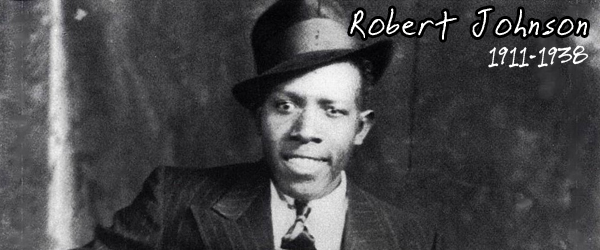

Robert Johnson — who is said to have sold his soul to the devil for prowess on the guitar and whose songs have influenced a host of famous musicians — was destitute when he died in Mississippi in 1938 at age 27. His estate is valuable, partly because of a collection of his recordings that featured a photo of Johnson on its cover and won a Grammy in 1990.

One of the photos is a studio portrait taken of the Mississippi bluesman by Hooks Brothers Studios in Memphis, Tenn. The other photo, known as “the dime store portrait” or “the photo booth self-portrait,” was taken by Robert Johnson himself.

On one side of the dispute were descendants of Johnson’s late half-sister, Carrie Harris Thompson. While they didn’t dispute that the copyrights to Johnson’s musical compositions belong to Claud Johnson, they argued that, as the heirs of Thompson, they were entitled to the fees generated from the Johnson photographs because they were Thompson’s personal property.

On Claud Johnson’s side were also record company representatives and a promoter who had signed a contract with Thompson in 1974 for her rights to Johnson’s work, photographs and other related material. In return, Thompson was to receive royalties that resulted from the promoter’s efforts.

The promoter later signed a deal with CBS Records to release a collection of Robert Johnson’s 29 recorded songs. CBS, later acquired by Sony, released a boxed set of Johnson’s recordings that sold more than a million copies and won the 1990 Grammy for Best Historical Album.

Thompson died in 1983, but her heirs argued they were entitled to royalties.

Claud Johnson, whose parents were not married, found out about his father’s estate in the early 1990s and was later named his father’s sole heir.

Leflore County Circuit Judge Ashley Hines ruled in 2001 that when Claud Johnson was declared the musician’s sole heir, the royalties specified in the 1974 contract were to go to him.

The Supreme Court found in 2004 that the question of whether the photos were the personal property of Carrie Thompson was never litigated. It directed Hines to rule on the issue.

Hines, without a trial, found in 2012 that the statute of limitations had run out on the legal challenge by Thompson’s heirs and the photos were Claud Johnson’s.

Supreme Court Presiding Justice Jess Dickinson, writing in Thursday’s decision, rejected arguments Thompson’s heirs that they didn’t sue because they thought they were the only heirs to the Johnson estate.