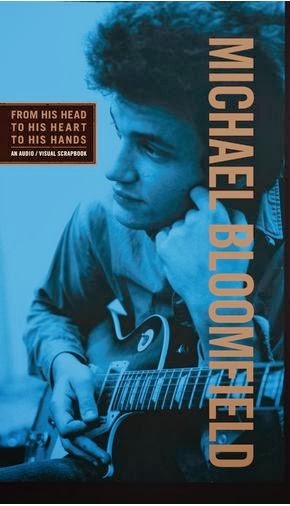

Michael Bloomfield – From His Head To His Heart To His Hands (Columbia Legacy)

Michael Bloomfield – From His Head To His Heart To His Hands (Columbia Legacy)

Lets go back to autumn of 1965. The summer ended with the release of Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited. From late July on, riding the top of the charts was the single, “Like A Rolling Stone.” Aside from it being the longest single ever released at the time, aside from the raging cry of the lyrics, it was hard to miss the band on that song, the piano by Paul Griffin, Al Kooper’s organ and that guitar that came in at the end of each verse playing a circular pattern that built up to the legendary chorus. It was also hard to miss the guitar that exploded after each verse of “Tombstone Blues” in a barrage of raw assault, and it was hard to miss that this same guitarist could lay back and play sweetly on “It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry” and gently echo the lyrics of “Just Like Tom Thumbs Blues”, making you feel that Easter time rain in “Juarez”. The lead guitarist on that album, as well as the single that would also race up the charts that fall, “Positively 4th Street” was Michael Bloomfield. The name seemed familiar because there was also a Michael Bloomfield who played piano on an album that had been released about six months before, So Many Roads by John Hammond Jr. And for those who dug a little deeper, his name could also be found on albums released the year before on Delmark Records playing guitar with Yank Rachell and Sleepy John Estes.

About six weeks after the release of Highway 61 Revisited, Elektra Records released the eponymous debut of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. The combination of Butterfield’s tough vocals, soaring harp and Bloomfield’s guitar was more than magical. It catapulted Mike Bloomfield to the front rank of blues guitar players and it sent guitar players on both sides of the Atlantic scrambling to learn his licks. It wasn’t just that Bloomfield played fast and seemingly endless totally fluid runs, it was that he imbued them with pure power and more importantly soul and passion. Bloomfield had a way of making every note he played mean something that went way deeper than speed and flash. The Paul Butterfield Blues Band not only took the blues world by storm, they conquered it.

Fast forward a year to the second Butterfield album, East-West. The album represented growth of the group and expansion of the music taking the blues to places it hadn’t been before. There were two lengthy instrumentals, Nat Adderly’s “The Work Song,” and the 13 minute title track which was literally a musical trip around the world filtered through the blues and dominated by Bloomfield’s guitar. That November, two days after Thanksgiving, they played New York’s Town Hall in a solo concert with this writer in attendance. The concert was energized magic featuring several songs from both albums, including the two East-West instrumentals and songs not on either record. To say the experience of seeing Mike Bloomfield play live was intense is putting it lightly.

Three months later, Bloomfield was gone from the Butterfield Band. Not long after his departure, Bloomfield announced he was putting together a new group that would be an “American Music Band.” He recruited two compatriots from Chicago, keyboardist Barry Goldberg, and Nick Gravenites, a singer and songwriter at the time best known for writing “Born In Chicago.” Also joining were bassist Harvey Brooks (who played on most of Highway 61 Revisited) an additional keyboard player, several horn players, and a powerhouse drummer and singer who was currently playing in Wilson Pickett’s band, Buddy Miles. Eventually, named The Electric Flag, the group debuted that June at the Monterey Pop Festival, and in March 1968 released their first album, A Long Time Comin’. American music turned out to be mostly blues and soul with a couple of explorations. Despite several good and some great tracks, the album was ultimately a let down. Three months after the album was released, Bloomfield was gone. From the beginning of the group, drugs, most notably heroin were a problem and that, combined with Miles’ massive ego, propelled Bloomfield’s departure.

Right around the time Bloomfield was growing disenchanted with The Electric Flag, Al Kooper, who had also formed a horn-oriented band, Blood Sweat & Tears from which he was forced out of, started working for Columbia Records as an A&R man and producer. He had an idea to make an album of jams with Bloomfield and let whatever happened happen. Kooper also felt that Bloomfield’s best playing had yet to be captured on disc. They jammed for nine hours in the studio, but when Kooper went to get Bloomfield for the next days session, he was gone. Steve Stills came to Kooper’s rescue, and the album Super Sessions turned out to be a big hit. Later that year Bloomfield and Kooper appeared together at the Fillmore East and the Fillmore West, resulting in a live album.

During the next decade, Bloomfield was involved in various projects and ill-fated bands, but none had the impact or magnetism of his initial work. Bloomfield would occasionally reunite with Butterfield or show up to special concerts with Chicago legends such as Muddy Waters, but his interest was always in putting the music first. He had no affinity for the music business or the stardom he could have easily achieved.

From His Head To His Heart To His Hands is a long overdue retrospective of Bloomfield’s work. A box set, it includes three CDs, “Roots,” “Jams” “Last Licks,” and a DVD, Sweet Blues: A Film About Michael Bloomfield, directed by Bob Sarles. There is an extensive booklet with liner notes by Michael Simmons, and producers notes as well as notes on the songs by Al Kooper, who compiled and produced the set along with executive producer Bruce Dickinson. According to Dickinson, more than anything, “the album was a labor of love and that we listened to it all”

The first two discs are basically in chronological order, with the third disc sort of bouncing back and forth between 1969, and various recordings, some live, some studio in the late 70s. The album starts with three previously unreleased tracks of Bloomfield auditioning for A&R man and producer John Hammond Sr. in 1964, backed by bassist Bill Lee, “Country Boy,” Bessie Smith’s “Send Me To The Electric Chair,” (listed as “Judge, Judge”), and then showing how he can pick Merle Travis style on “Hammond’s Rag.” The last track is a total surprise because it shows a whole other side of Bloomfield’s playing, one he rarely explored, and the dexterity of speed of his picking is mind blowing.

The next track, “I’ve Got You In the Palm of My Hand” is from an actual sessions in Chicago with musicians picked by Bloomfield including Charlie Musselwhite on harp. Unfortunately, producer John Hammond suffered a heart attack and Bob Morgan took over for “I’ve Got My Mojo Workin.” Hammond and others at Columbia loved Bloomfield’s playing, but weren’t sure about his vocals, and the tracks weren’t released until years later.

Two tracks from the Highway 61 Revisited sessions come next, “Like A Rolling Stone,” but stripped of Dylan’s vocals and “Tombstone Blues” with The Chambers Brothers joining in on the chorus. The song, no matter which version, is one of the ultimate Bloomfield tracks period.

After a brief snippet of Bloomfield talking in his classic way about Butterfield from an interview, two songs from the first Butterfield album, “Born In Chicago” and Little Walter’s “Blues With A Feeling” follow, and immediately you’re reminded how great the Butterfield Band was. “East-West” concluded the Butterfield Band portion of the set. Undoubtedly, some listeners will quibble over which track was selected, but when creating compilations like this, often its not a choice of what to put on, but what to leave off and for each track selected, theres always going to be another track thats just as good. “Blues With A Feeling” in particular shows the Butterfield Band wasnt messing around. They were putting themselves right up there with the best. Bloomfields playing sounds just as astounding now as it did almost 50 years ago.

The Electric Flag portion starts with “Killing Floor,” in a speedy version where they’re not trying to emulate Wolf, letting the horns play what is the main guitar riff on Wolf’s version allowing Bloomfield to let loose, which he does the entire song. Also included is the straightest blues from that album, “Texas” with Buddy Miles singing with Bloomfield answering the vocal with his lead. As strong as Miles vocal is, its Bloomfields solo that makes the song. Two previously unreleased live tracks come next that give a glimpse how great the Electric Flag could have been if they’d kept it together. Their portion and disc one ends with the brief snippet of “Easy Rider” that closed the first Electric Flag album.

Disc Two is comprised of the jams Bloomfield and Kooper did in the studio as well as on onstage at the Fillmore West and the Fillmore East. The version of “59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin’ Groovy) is new in the sense that Kooper took the best of Bloomfield’s solos from both Fillmore’s and created a new version to showcase them. The jam disc is not strictly instrumental. Kooper sings on the previously mentioned track and Bloomfield contributes vocals on quite a few. What comes through constantly, particularly on the bluesier tracks such as Albert King’s “Don’t Throw Your Love On Me So Strong” is Bloomfield’s constant inventiveness and his taste. He just simply knew what to play, and more often than not what some would consider the incidental runs, the ones leading up to the maximum impact peak licks are often more amazing than when he’s going deliberately for maximum impact. One of the cooler jams is their nod to The Band on “The Weight,” which also comes off as a tip of the hat to Booker T & The MGs in both feel, groove and Bloomfield’s Cropper-esque riffs.

The third disc opens with a hysterical live finger-picked acoustic track, “Im Glad Im Jewish,” recorded live at McCabes, and gives a good idea not only of Bloomfield’s sense of humor, but how he could interact with an audience when he wanted to. After another track with a band from the same gig, the album moves back to 1969 for a Muddy Waters track from the Fathers & Sons album that also includes Butterfield on harp, Otis Spann on piano, Sam Lay on drums, and Duck Dunn on bass. Also included are a few tracks from various Columbia albums, at the time done with Nick Gravenities, and a Janis Joplin track, “One Good Man,” with Bloomfield on playing side at the beginning, and then letting loose with an astonishing (non-slide) lead on the break, which he continues to the end. After a couple of more tracks from his 1969 albums, the album returns to the live stuff at McCabe’s, alternating between acoustic tracks and tracks with a band, culminating in a previously unreleased track recorded at New York City’s Bottom Line that was originally a bootleg, “Glamour Girl,” that included Kooper on piano, who stopped by the gig to say hello, and ended up playing on the entire set.

What is clearly evident on the late 70s tracks, is that Bloomfield is no longer the take no prisoners, out to prove something guitar player. There is a feel throughout those tracks of someone who just wants to play. This does not mean his playing is less impressive, because in every way he could still amaze, as the solo on “Glamour Girl” amply demonstrates.

However, that take no prisoners style did appear one last time. On November 15, 1980 Bloomfield joined Bob Dylan onstage at San Francisco’s Warfield Theater and sat in on two songs, “Like A Rolling Stone,” and “The Grooms Still Waiting At The Altar.” The second song is included here in its first legitimate release. This was the only time that Dylan (so far) played the song in concert, and when Bloomfield comes in, he takes his solo to stratospheric heights. This would turn out to be Bloomfield’s last performance onstage. Exactly three months later, he was found dead in a car in San Francisco.

Appropriately, the album ends with a brief, but astonishingly beautiful excerpt of Bloomfield playing Joseph Spence’s “Hymn Time.”

The fourth disc is a DVD of Bob Sarles’ film, Sweet Blues: A Film About Michael Bloomfield. The key word in the title is “about”. This is not a film of Michael Bloomfield, though there are scenes of him playing as well as a couple of complete songs. Sarles interviewed several people who worked with Bloomfield, including Elvin Bishop, Nick Gravenities, Mark Naftalin, Charlie Musselwhite, John Hammond and Al Kooper, as well as numerous musicians who were influenced by him, and also Bloomfield’s mother and brother, and several other people, including Bill Graham and B.B. King.

Near the end of the film is a poignant clip of Bloomfield at The Bottom Line solo, playing “In My Time of Dyin'” on a Gibson acoustic. His playing is far from perfect and he knocks his slide against the frets, but at the same time, something compelling lingers about the performance. He is clearly into it.

What Sarles’ film does through the stories, the interviews with those that knew him, and interviews with Bloomfield himself, is present a vivid portrait of who Bloomfield was; his passion, his brilliance, his humor, and his neuroses, his chronic insomnia, his problems with drugs.

With any luck, From His Head To His Heart To His Hands will do what it’s intended to do and restore Michael Bloomfield to the place of prominence he so richly deserves in the history of American music. He was without question one of it’s greatest guitarists.