Whether its comic book characters, novels or musical icons, when the film version comes out, the producers always seem to re-invent the back story and just twist our vision of a beloved entity into something unrecognizable to suit a story line that matches what the studio thinks the largest number of people will shell out money to see.

Never mind that the only recognizable element left is the name that draws you in.

They did it with Johnny Depp, who wears a headdress sprouting a crow that looks like he’s taking a crap on Tonto’s head in The Lone Ranger. They turned Stephen King’s Under The Dome into an endless string of unresolved story lines to go into a second season on NBC TV’s summer season. In the film “Cadillac Records” they turned Chess Records founder Leonard Chess into a womanizer having an affair with Etta James. Hell, they wrote his brother Phil right out of the story and killed Leonard off before he sold the label.

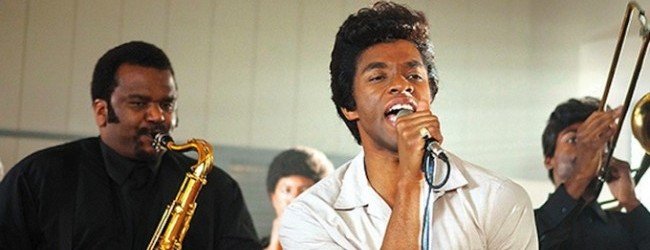

Thank God they didn’t turn James Brown into a joke on Get On Up. I think I’d have had to go postal if they had.

I first heard James Brown in 1964 on WILD… “wild in Boston.” While the rest of my friends at Tufts University were listening to WBCN, a formerly all-classical FM station that switched over to the new underground music with hip deejays that included Peter Wolf, later of the J. Geils Band, I would dial up Wild in Boston. The frenetic all-black station at the far end of the AM dial was just beyond Arnie The Woo Woo Ginsberg on WMEX 1520, an AM rocker.

I loved listening to these over the top black deejays play James Brown and other R&B hit makers of the day. At the time, Brown hadn’t broken through to the blues audience that was hearing the Wolf and Muddy on FM college radio stations. Those stations would play the Stones doing Irma Thomas’ “Time IS on My Side.” Then they’d play the original while WMEX was all about Motown.

So when my friend Bill Nowlin and I went to see James Brown in Boston, we were the only white kids in the audience. We knew Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis, but this guy was doing splits and turning keyboards, guitar and horns into dangerous vehicles of percussion. It was the first time I’d ever been in an audience where I was in the minority. Bill had his pocket picked, and we were tear gassed for the second time in a few weeks. The other time was at a Stones concert.

This was about the time when the Stones were picked to close the T.A.M.I. show in L.A. in the fall of ’64. Filmed in front of a large audience of teenagers from a local high school, the film featured a gumbo of rockers ranging from The Beach Boys and several Motown acts including Smokey Robinson & the Miracles and The Supremes to British invasion acts like Jerry and The Pacemakers and Billy J. Kramer & the Dakotas. At the last minute the producers decided to headline the Stones over James Brown. The Stones’ were still “England’s Newest Hit Makers” while James Brown in the last decade had become “Soul brother number one,” the equivalent of Elvis is the black community, but virtually unknown to white pop music fans. Mary Wells of The Supremes gave me the African American perspective in a 2012 interview.

“Everybody on that show had had loads of hit records, and we were all bona fide stars at the time. All of us assumed that James Brown would end the show. Then the word got out that this new group called the Rolling Stones were going to end, and they’re saying, ‘How can the Rolling Stones end the show over James Brown?’ James was back there going (imitates James Brown’s guttural grunts) ‘The Rolling Stones? They’re gonna close the show over me?’

“And the Rolling Stones were in their room going, ‘We’re closing the show after James Brown? How can we do this?’ It was so funny, and of course at the end of show everybody, Marvin Gaye, the Supremes, everyone was on the side of the stage because we wanted to see how in the world this was going to happen.

“So, James forewarned (everyone) that he was going to make the stage so hot the Rolling Stones could not come on, and he did it because every time the robe would come back on, he would kick it back off, and he did it more than he was supposed to do. He wanted to make sure they could not come on after him, but then after that, Bill (Wyman) said they became best friends. James said, ‘Man, I sure didn’t want you guys to go on.’ The Rolling Stones went out there, and they too had the girls screaming. So it was a fun kind of thing.”

In the new film Get On Up, Chaswick Boseman playing James Brown saunters off the stage after his performance at the T.A.M.I. Show looking straight ahead and says to the Stones standing in the wings. “Welcome to America.”

It was one of those pivotal moments in history where the sheer force of the music contributed to a quantum change in society’s attitudes. The 1964 Civil Rights Law put the power of the law behind African Americans as the youth of America became an economic and social voice that realized bands of white Brits were selling the American heritage back to a part of society that had been ignoring the origins of American music.

Mick Jagger co-produced the film and told Gayle King on “CBS This Morning” that he got many of his moves from Soul Brother Number One. The T.A.M.I. show made the Stones a member of the new fraternity in 1964, and Mick returns the favor in Get On Up. He understands the incredible role Brown played in bringing the races closer together.

“I didn’t do (“I’m Black and I’m Proud”) to separate,” James Brown told me in 2002. “I wanted to write and (tell) the people that were going through things. I wanted them to know the day wasn’t over. You’ve got to (live) your life. You can straighten it out. I want you to know my love is unconditional. I love people regardless of what they do. I may not like what they’ve done, but that’s God’s business.”

By 1968 when Martin Luther King was shot, I’d been sucked into the selective service system, an activated Army Reservist stationed at Fort Lee, Virginia. Many of us in our unit would drive eight hours back and forth from Virginia to Schenectady, New York to be with our families knowing that we would eventually be shipped out to Vietnam. One Monday night after I’d been up for 36 hours straight on one of these flash trips, my Army company put us on alert for riot duty in D.C. James Brown had just played Boston the night of the King shooting and calmed the rioters down. They called off our riot duty. If I’d been put on the front lines of an urban riot that night in the condition I was in, I wonder if I’d be alive today.

Say what you will about James Brown’s private life, he’d been through hell as a child, and he got it. He understood what racial harmony was all about. His chilling words echo in my brain even now. Our 2002 interview was conducted at a time when he gave back to his hometown of Augusta, Georgia with Thanksgiving turkeys and other gifts. He took time out to tell me a story about his childhood. “There was a cookie place, and while they was making the cookies, they would drop a lot of batter on the floor and (we would) give them a nickel. They’d scrape it off the floor, and we’d take it to school and eat it. That’s how bad it was. I will always be in love with humanity and thank God for all he’s done. We’re paying back to the community. You want to thank God and show him how much you appreciate it.”

The film presents James Brown warts and all, but I came away from it saying to myself, yeah, this does service to a guy who may have saved my life and whose music changed the way blues relates percussion to melody while its sheer power broke down barriers between the races by saying we are different but we can all dance to the same tune.