Luther Allison’s son Bernard used to hide in the closet when Johnny Winter came over to the house because he was afraid of the albino with pink eyes, but Johnny taught Bernard that the secret to playing slide guitar is open tuning. Dad never did that.

Luther Allison’s son Bernard used to hide in the closet when Johnny Winter came over to the house because he was afraid of the albino with pink eyes, but Johnny taught Bernard that the secret to playing slide guitar is open tuning. Dad never did that.

Stevie Ray Vaughan showed a young Bernard the price one pays for being on drugs, and that was before Stevie went into rehab. “I found it very easy to play “Texas Flood” because it’s flooded with Albert King which I grew up with,” recalls Bernard. “Albert King is pretty much my top dog as a guitar player and still is. So then when Stevie realized who I was, he was like, “Wow. Come out with us. Come jam with me.”

And when it came time to show his son the ropes of the road, Dad called Koko Taylor who made Bernard the leader of her band at age 18. “I know it was never told to me, but I know he pretty much set that up because he was in Europe, and he really wasn’t sure that I was going to pursue the music. So once I graduated, Koko gave me the shot, sort of like a test for the road.”

And when Dad was lying on his death bed with a brain tumor in 1997, he told his son to go on tour as his first American album Keepin’ The Blues Alive was being released and to skip his own father’s funeral.

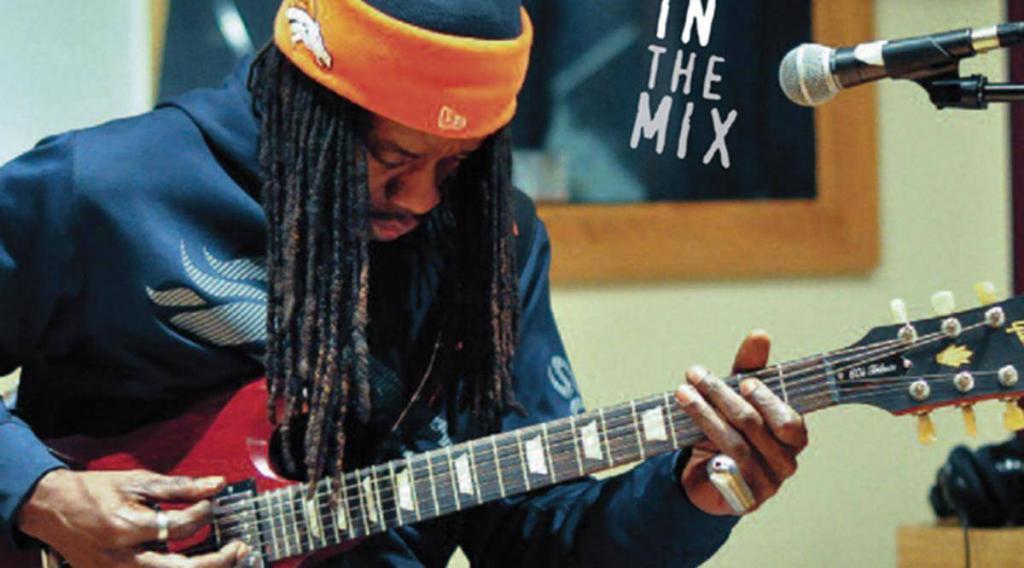

Yes, Bernard Allison comes from great blues stock. That said, his latest album In The Mix out Tuesday, March 17, is going to surprise you. I can almost guarantee it.

Led Zeppelin forever will be remembered for the cathedral guitar screams on “Stairway to Heaven” even though they recorded many ballads. Screamin’ Jay Hawkins built a whole career around the crude Halloween theatrics of “I Put A Spell on You” even though he had an operatic voice. And Bernard Allison for 30 years has carried the torch of his father who, for my money, was the only Chicago blues guitarist ever to challenge Buddy Guy as the most energetic, splashy and awesomely dexterous electric guitarist in blues.

But Luther’s potentially biggest break came when he became the only blues artist signed to Motown, the home of Detroit soul, and his best record was his posthumous two-CD set Live in Chicago released by Alligator Records, a tour-de-force that shows his diversity and dynamics that go way deeper than his screaming guitar. Luther’s been gone 18 years now, and if you’re looking his son to put a junior at the end of his name, you’re in for a big surprise on his just released In The Mix album.

“I didn’t want to do a good time, in-your-face album,” he explains. “You have your guitar fans and all of that, but I think I’ve proven myself as a player or soloist. I just wanted to highlight my arrangements, my writing ability and to really show people the unity of the group, the coloration of the instruments.”

And that’s just what he does. On In The Mix he covers two of Dad’s songs, “Move From The Hood” and “Moving on Up,” but where Luther buries his band in testosterone banshee guitar wails on a live version of the song recorded at the 1995 Chicago blues Festival on his Live in Chicago album, Bernard showcases his band, and defines himself in his Tyrone Davis-like soul vocals as much as he does his guitar solos.

“I’m more comfortable singing these songs that I’ve always wanted to sing like the Freddie Kings and the Tyrone Davises ’cause I grew up with all of this stuff, but never really put it on record. So it was just to bring back those great names that we’ve lost and put it in the ear of the youngsters, and hopefully they’ll go and do some soul searching because there’s some amazing music out there that’s kind of died away once those guys died away, and I don’t think it’s fair to them.”

There’s more Memphis soul than Chicago blues in these arrangements, and while he doesn’t want to lose the guitar fans who still idolize his dad, he’s looking at an album here that will please his base audience of Europeans. He’s lived in Paris mostly since 1989 and played exclusively in Europe for 12 years. This is an audience that looks at blues as art as much as many Americans tend to hear the genre more from the gut.

“I credit my group,” he says. “Without them, I’d be a John Hammond for instance. I could do that as well, but at this stage of the game I’ve recorded numerous records, and they’re all semi in the same game, but now also being a little bit older and my voice is pretty much where it’s gonna stay now. I focus more on my vocals way on top of the mix and there’s plenty of room for me to play rhythms and spot leads.”

“Lust for You” co-written with Ronnie Baker Brooks is a particularly unusual song that most people in a blindfold test would never associate with either Bernard or Ronnie, the son of another Chicago blues stalwart, Lonnie Brooks, whom Bernard has known since they both shared the basketball court as children.

“I basically arranged the music, and Ronnie wrote the words, and I decided I should try to do this, but I actually changed the arrangement to be slower. It was more leaning toward the rock edge than how we laid it down. The way we did it the drums turned the song totally around. It freaked me out because I had no idea what my drummer was gonna play. I’m like ‘Whoa, what do I do with this? This is pretty cool, kinda like the old country western flavor to it.’

“It’s interesting how it came out when I hear the first version of Ronnie’s and mine and then hear the newer one. It’s pretty cool. It’s unique, and the solos are pretty trippy on that. The Hammond B3 solo (by Mark “Muggie” Leach of Buddy Miles fame) as well as the guitar solo. It takes me out of the Stevie Ray-ish, Albert King-ish vibe when I can kind of play it with the song. Don’t worry about being too bluesy or too funky at the same time. It was just a nice track with the tempo how it set right in the middle of the record and kind of toned things down before we go to the next song, basically.

“When Ronnie and I wasn’t in school, we just were together in a room playing guitar or playing basketball, or we both knew we had the potential of playing music. That’s what we wanted to do and be like our fathers, but we also understood it’s gonna take not just the name of our creators, our dad’s. We have to be true to it, and put out hearts into it.”

Bernard co-wrote “Call Me Mama” with his mother whom he credits as a big influence on him as well as his dad. “I remember my dad said, “You always gotta do something for the ladies,” and this CD is a lot women friendly, and lots of my friends that have heard it, their wives are like, “Wow, we gotta have a couple of copies of that. We really like that ’cause all women aren’t into all that guitar stuff. They prefer the lyrics and things like that as well as the Tyrone Davis thing.

“If you’re talking about playing in the south, and you want some of the black public to come to your shows, that’s the way you gotta go because they’re really not primed to hear a bunch of guitars. They want to hear the voice and the emotion and the crooning and the things like that. So I said, “I can do that. I grew up with that. It’s in me, you know.”

One often wonders how great artists who died too young might sound had they not passed. What would maturity have done for Luther Allison? It would be presumptuous to hypothesize that he would sound like Bernard does today at 49, but it is exciting to hear Bernard’s hugely eclectic influences coalesce into an album that appeals to a broad spectrum of the blues audience including guitar lovers, women, Europeans and –dare I say – African Americans. One thing is sure. Dad would be very proud of his youngest of nine children.

“My dad was originally from Arkansas, but pretty much got his thing from moving to Chicago, and that’s where everybody started saying, “Luther Allison Chicago blues” which he didn’t like because he liked to play Otis Redding or Jimi, and he went to Europe where they allowed him to play what he wanted to play as opposed to play what the public wanted him to play.

“And it kinda fell on me the same way and, when I went to Europe, they just accepted everything that we had to offer and if we wanted to get rocky or funky or take it like back to the Delta, they supported it and appreciated it and didn’t label it. They’re like, “Wow, these guys are blues-oriented, but they play everything. How do they do that? How do you interpret all that music into that style?

“I always say I’m carrying on the Allison tradition the best that I can and hopefully I can keep bringing in some Luther Allison songs as well as some Bernard Allison songs and let ’em know that, ‘Hey, we’re still out here to give. My daddy’s still with me. If it wasn’t for him. I wouldn’t be doing it.’”