Exclusive deals are entered all the time as part of the music industry. Often times, artists have exclusive deals with managers, exclusive deals or at least exclusive territorial deals with their booking agency, and most commonly with a record labels. Though exclusive arrangements aren’t inherently bad, and are often necessary, they can turn sour. For R&B pianist/guitarist and vocalist, Wilbert Harrison, his exclusive agreement with Savoy Records resulted in litigation that stalled his career at the very height of his success.

Exclusive deals are entered all the time as part of the music industry. Often times, artists have exclusive deals with managers, exclusive deals or at least exclusive territorial deals with their booking agency, and most commonly with a record labels. Though exclusive arrangements aren’t inherently bad, and are often necessary, they can turn sour. For R&B pianist/guitarist and vocalist, Wilbert Harrison, his exclusive agreement with Savoy Records resulted in litigation that stalled his career at the very height of his success.

Wilbert Harrison, born in Charlotte, N.C. in 1929 began his recording career in 1953 after having served in the Navy. Having limited success with his early recordings, he moved to New Jersey. No longer under contract with the Miami-based Rockin’ Label, he was recruited by producer; Fred Mendelsohn. Mendelsohn was instrumental in getting Harrison signed to an exclusive recording contract with Herman Lubinsky’s Savoy Records. After limited early success on Savoy, Harrison was eager to keep trying to for an elusive hit, but the label had lost confidence in him. After attempts of covers of various genres, Savoy Records tried by releasing a few of the original songs written by Harrison. Still Harrison had no success. Some accounts suggest that Lubinsky released Harrison from his contract outright in a civil manner. Bobby Robinson [owner of Fury Records], however, would recount in an interview with John Broven, that Lubinsky allegedly pulled a gun from his desk drawer, telling Harrison “Get the hell out of here. Don’t darken this door anymore. Go to record for who the hell you want to record. Record for anybody, just don’t come here no more.” After that, Harrison decided to move back to Florida where he briefly recorded for Glades Records. Eventually, he would be back in Charlotte, North Carolina.

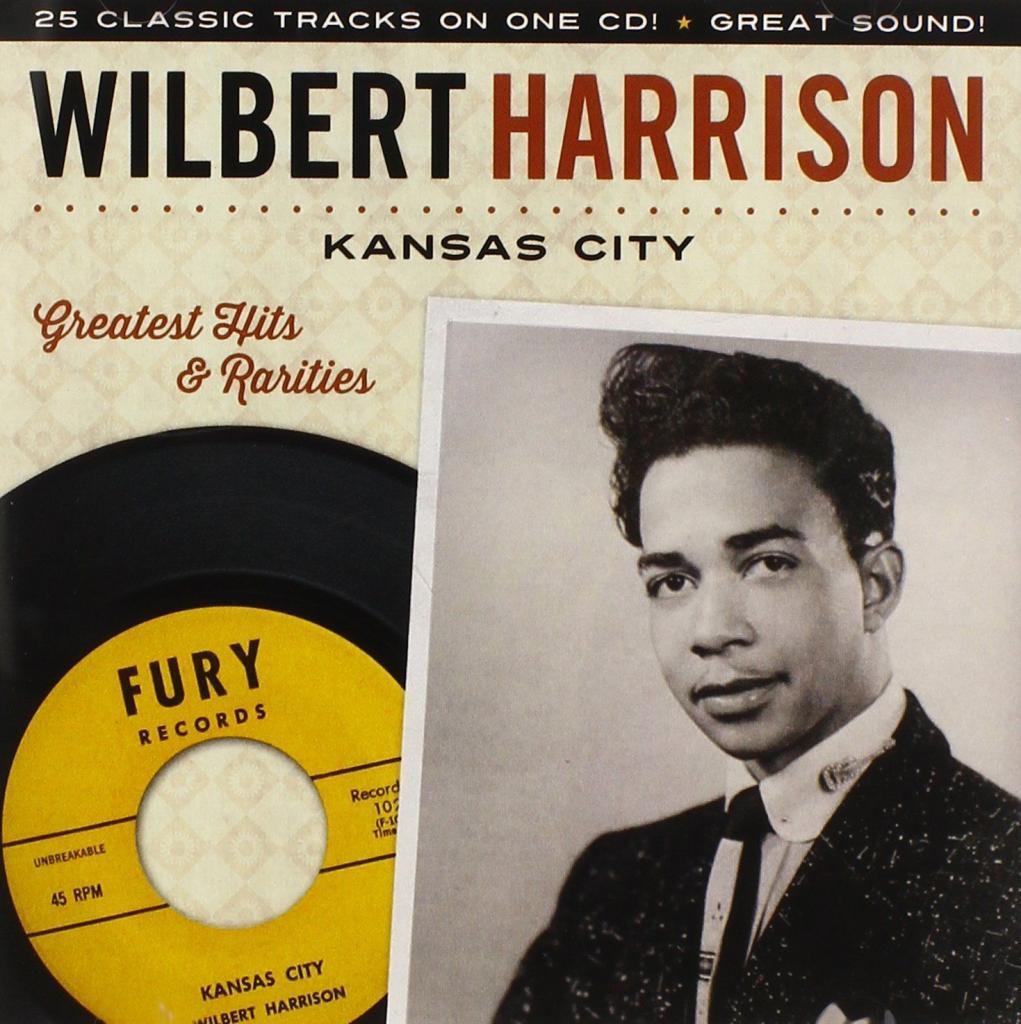

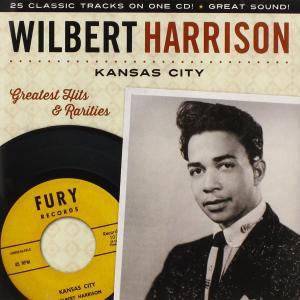

In 1959, Harrison’s new manager, Marshall Sehorn introduced him to Fury Records owner; Bobby Robinson. Fury Records was started in 1957 and had released dozens of recordings but hadn’t had any hits. Robinson quickly booked a recording session with Harrison and local musicians to do a song that Harrison was performing in his live shows. The session resulted in what would be Wilbert Harrison’s biggest hit; Kansas City. Originally written by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller and released in 1952, under the title K.C. Lovin’, by Little Willie Littlefield, Harrison’s version quickly sold over 3 Million copies and hit #1 on both the Pop and R&B Charts.

With the success of Kansas City, Lubinsky filed suit against Fury Records for $100,000.00 on the basis that Savoy Records still had an exclusive deal with Harrison. The lawsuit with Savoy Records tied up Robinson and Fury Records legally and financially. Wanting to capitalize on the new-found success, Robinson set-up a new record company called Fire Records. The releases on Fire Records became successful, but Robinson was unwilling to risk a follow-up release on Harrison until the legal issues were resolved with Savoy Records. The result was that Harrison, despite having a number one hit on both the Pop and R&B charts was unable release a follow-up for over a year. The legal dispute would eventually settle out of court, after almost a year of negotiations for an estimated $13,500.00, with Robinson maintaining that at the time of the Kansas City recording, he was unaware of any contractual obligation to Savoy.

Interestingly, while Fury records was defending the lawsuit with Savoy Records, Armo Music which represented the publishing for Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller also successfully sued Fury Records over the song, insisting that Kansas City was an infringement of the earlier song K.C. Loving.

Bobby Robinson would continue producing blues and R&B hits throughout the late ‘50s, 60’s with artists like; the Shirelles, King Curtis, Gladys Knight & the Pips and Elmore James. As an early producer of rap music, he also produced hits in the late 70’s and 80’s with artists like Grandmaster Flash and Doug E. Doug.

Unfortunately, Harrison would never be able to replicate his success with Kansas City. He recorded several follow-up songs but with no success. He would eventually crack the Billboard Top 40 in 1970, with Let’s Work Together Pt. 1. He died of a stroke in 1994 while living in a nursing home. He toured extensively with a band and as a solo artist. In 2001, his version of Kansas City received a Grammy Hall of Fame Award and was later named by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame among the 500 Songs that shaped Rock and Roll. In 2009, Harrison was inducted into the North Carolina.

Though he wasn’t, technically, a One-Hit Wonder, one cannot help but wonder how Harrison’s career would have been different had his exclusive recording contract with Savoy Records not stalled his career while he was at the top of the charts. In 1959, Harrison was a talented vocalist and multi-instrumentalist, with a knack for picking and writing good tunes. It was a time era when R&B artists, if they were successful at crossing over to the Pop Charts, could truly become household names and maintain decade-long careers with just a few well-timed hits. Harrison’s situation should serve as a lesson for all artists to enter cautiously into contracts, but to make sure that when a deal is over the dissolution is also clearly documented.