Royalties from songwriting can make for a very lucrative music career even when a singer-songwriter doesn’t have many hits as a recording artist. Unfortunately, many blues songwriters historically haven’t been able to negotiate contracts that take full advantage of the potential opportunities, and even when they do, they have often been denied royalties owed. It is a too common tale that legendary artists have had to wait years or decades to receive royalties, and it is often required to pursue legal action to receive a fraction of what is actually owed. The story of “The Father of Rock n Roll”; Arthur Big Boy Crudup is the king of those stories.

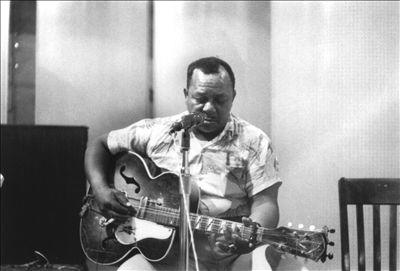

Born in 1905, Arthur Crudup started his musical career at a young age singing Gospel music in the church choir. In 1940, as a member of the gospel group the Harmonizing Four, Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, first travel professionally to Chicago. After leaving the group, Crudup began performing on the streets on Chicago as a blues singer and guitarist. It was on the streets of Chicago, that Crudup came to the attention of Lester Melrose. Crudup recorded his first of many records in 1941. He would continue to write and record many original works for Bluebird until 1952.

Lester Melrose was working as a talent scout and producer for RCA/Victor’s Bluebird Records. The Bluebird label was created in 1932 by RCA/Victor in part to capitalize on the growing market for urban blues singers. Melrose is primarily remembered for scouting, recording and producing some of the early greats among the pre-war Chicago blues-scene like; John “Sonny Boy” Williamson, Tampa Red, Washboard Sam, Roosevelt Sykes and Big Bill Broonzy. When most people think of Chicago Blues, they think of the post-World War II artists like Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters and Little Walter, but there was already a successful blues scene in Chicago by the early 1940’s and Melrose had a knack for finding and producing quickly recorded and produced hits. Melrose stepped into the role of manager for Crudup, promising him 35% for his recordings and original works.

Crudup’s royalty checks rarely amounted to more than an occasional $10-$15 check. As was common at this time, Melrose listed himself, as well as, Crudup and also received a publishing royalty from the music. Melrose arranged a publishing contract for Crudup with Melrose’s Wabash Music Publishing Company.

Despite successful record sales of Crudup’s songs, Crudup would give up his music career due to financial instability. After unsuccessful attempts to obtain royalties from Melrose, Crudup would go back to manual labor, after recording for other labels, under other names. Many of his songs were successful and were being covered by other blues artists, including Bobby “Blue” Bland, Big Mama Thornton and B.B. King, but he was still not receiving royalties.

In 1954, when a young Elvis Presley recorded Crudup’s “That’s All Right”, Crudup again received national recognition, but still was not receiving royalties. Eventually, Presley would record three of Crudup’s songs; “That’s All Right”, “My Baby Left Me” and “So Glad You’re mine”. Many of Crudup’s songs would become blues standards after being re-recorded by the biggest names in blues and rock n roll, like Johnny Winter, Paul Butterfield, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Canned Heat, Elton John, Rod Stewart among others.

In 1968, Dick Waterman befriended and convinced Crudup to begin performing again. Serving as Crudup’s manager, Waterman began booking Crudup and getting his career going again. Waterman was instrumental in registering Crudup with the American Guild of Authors and Composers (AGAC). Before retiring from the music business, Melrose sold the his interests in Wabash Music Company to Hill & Range Publishing Co.. In 1972, the director of the New York office for the AGAC contacted Waterman to let him know that an agreement had been reached with Hill & Range to cover past due royalties.

Crudup, Waterman and Crudup’s sons drove to the Hill & Range office in New York to sign the agreement and receive the $60,000.00 check as an initial royalty payment. As part of the agreement, Crudup’s sons would need to forego any future claims against Hill & Range for back-royalties. When I spoke with Waterman, he explained that they met with the Attorney for Hill & Range. After they had signed the agreement, the Attorney went to get the check signed. The Attorney returned within a few minutes. Waterman described the look on the attorney’s face as “pale and distressed”. The company executives refused to sign the check. The attorney stated that it was the company’s position that $60,000 was far more than Crudup could hope for in litigation. Crudup, confused by the situation, asked Waterman what was going on. Waterman explained that the only chance they had of getting any royalties was to sue, and that they’d never have a chance of successfully suing an elderly, Caucasian widow in Florida, where Melrose and his wife had retired to.

Waterman describes the scene outside the Hill & Range office with Arthur Crudup in his book “Between Midnight and Day”. Waterman was frustrated with the whole situation. However, Crudup just thanked Waterman for his efforts because he reluctantly had come to terms with never receiving what was owed to him.

While, Crudup would never see any additional royalties, the story doesn’t end there. Crudup would pass away the following Spring on March 28, 1974. After Crudup’s funeral, Waterman spoke with an attorney that he’d worked with on previous record negotiations for other artists. The attorney, knowing that Hill & Range was still collecting large amounts of money from Crudup’s music, said that they need to “shut off the money spigot” from the record companies to Hill & Range.

It wasn’t long before things turned in Crudup’s favor. Hill & Range had begun negotiations to sell their catalogue to Chappell Music. When Chappell found out about the legal dispute between the Crudup Estate and Hill & Range, Chappell refused to move forward with the deal until it was resolved. It was just the leverage they needed. Hill & Range quickly contacted Waterman and the Crudup Estate. Hill and Range now had the motivation to settle. According to Waterman, the very first check was signed over to the Estate for just over $248,000.00, over four times what they been unwilling to pay just a few years earlier.

Waterman estimates that the Crudup estate has received over three million dollars in royalties over the last several decades. Waterman said that he regrets that Arthur never got to see a penny of it. The catalogue is still incredibly valuable. Artists in many genres continue to record Crudup’s songs with success and film makers wanting to cover the story of Elvis Presley are hard-pressed to make the story without including Elvis’ version of Crudup’s “That’s All Right”. While Crudup died with little money to his name, his legacy will continue with his music and the “Father of Rock N Roll” will continue to be remembered by his marker along the Blues Trail, his induction into the Blues Hall of Fame, and hopefully an induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a true pioneer.