Blues scholars and researchers often debate the origin of blues music. While some argue that the modern blues found its true origins in the cotton-fields of the Mississippi Delta or in the Piedmont region of the Carolinas. Others debate that the blues originated in Africa and were transplanted to the United States with the slave-trade.

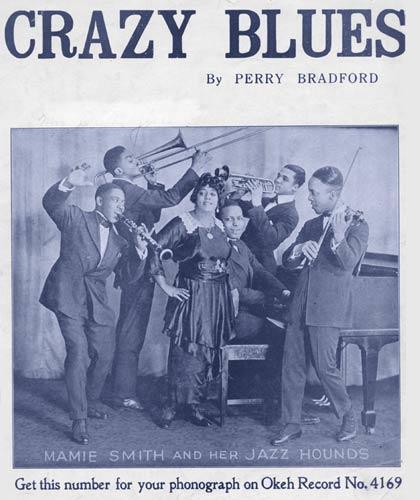

While it is difficult or impossible to find agreement on the true origin of the blues, there is little debate that the first “Blues Hit” was the 1920 Recording of “Crazy Blues” by Mamie Smith and her Jazz Hounds.

There were many songs recorded by African-American artists and plenty of songs with “Blues “ in the title prior to 1920, however it was the Perry Bradford penned tune “Crazy Blues”, recorded by Mamie Smith that opened the market for future blues-artists. Mamie Smith’s recording would quickly sell over 75,000 copies, primarily to an African-American audience.

That one recording, which was recorded under the direction of music industry-pioneer Ralph Peer of OKeh Records, lead to a new industry that would lead to other labels wanting to cash-in on the new opportunity and music market. Artists such as Robert Johnson, Charley Patton, Blind Willie McTell, Son House, Alberta Hunter, Blind Lemon Jefferson and Bessie Smith would soon find recording opportunities with labels such as Vocalion Records, Columbia Records and Paramount Records.

Music-Industry Attorneys often say; “Get a hit, get a writ”. In the last few decades of the music industry, when a song becomes a hit and makes a lot of money, it seems almost inevitable how quickly opportunistic individuals come out of the woodwork to get a piece of the action. This phenomenon seems to have been true even in the early infancy of the music industry. A piece of the action would have included all of Bradford’s first royalty check that was said to be for $100,000.00. The 1921 lawsuit against Perry Bradford, the songwriter that wrote “Crazy Blues” seems to suggest that the courts were addressing entertainment law issues very early on.

The plaintiff, Max Kortlander (Arranger, Publisher and eventual President of QRS Recording Laboratories), alleged in court that he purchased, for a fee, all the rights to “Wicked Blues”. He further alleged that Bradford, changed the titled of the piece to “Crazy Blues”, filed a new copyright registration and had licensed the original work under the new title to third parties.

Interestingly, the claim was not a Copyright claim, which would have required the case to be brought in Federal Court, but rather the claim was for an injunction against the further sale and publication of the sheet music and “phonograph recordings”, as well as an accounting for royalties for the sale, publication and reproductions.

The New York Supreme Court, in its opinion of the Kortlander v. Bradford, et.al. case (190 N.Y.S. 311), summarizes the factual basis, that Perry Bradford original composed the song entitled “Wicked Blues” and without question found that there was sufficient basis for a claim.

The Court, in its opinion, did not address a comparison between “Wicked Blues” and “Crazy Blues”, but Bradford and the additional defendants in the case; Victor Talking Machine Company (RCA/Victor), Mel-O-Dee Music Company, Thomas Edison among others, simply argued that the Plaintiff failed to sufficiently state facts to warrant a claim and that the State Court lacks jurisdiction to hear the case and should remove the case to Federal Court.

The Court addressed similar cases with regard to the assignment of ownership in literary works and found in favor of Kortlander, granting him the right to move forward with his claims. The case never went further. Bradford, who was at the time making a lot of money and had become a much sought-after composer, simply settled the dispute out of court with Kortlander for an undisclosed cash payment.

Though Bradford would continue to compose, publish and produce hits, he would soon be out-shadowed by the likes of W.C. Handy and other blues-writers. Bradford’s reign over the blues-industry wouldn’t last more than another few years and his name would disappear amidst more popular blues singer-songwriters.

It is still interesting that the first big blues hit would be the basis for one of the early music-industry legal battles. It wouldn’t be the last time that Bradford would see the inside of a courtroom. He would go on to be the defendant in more civil and criminal litigation.