For fans of Walter Trout, his wife Marie is now a family member, just another side of Walter Trout’s life that has been generously shared with them to a relatively substantial degree these past almost two years, somewhat due to necessity, and invariably, out of love and mutual respect. While Marie, as Walter’s manager, had been familiar with his fans on many levels, when he became sick and in need of the liver transplant and the rehab and recovery that followed, she really got to know his fans, and what was in their hearts.

She and Walter both experienced just how much the two of them were loved by the fans. The fans, for their part, saw how much Marie and the family were struggling and battling to save Walter and give him a fighting chance; their love and respect for her grew exponentially. They were also able to show their love for the family by raising enough money to allow them to travel to wherever Walter needed to be for his care, to keep their home, and help with the immense medical and associated expenses.

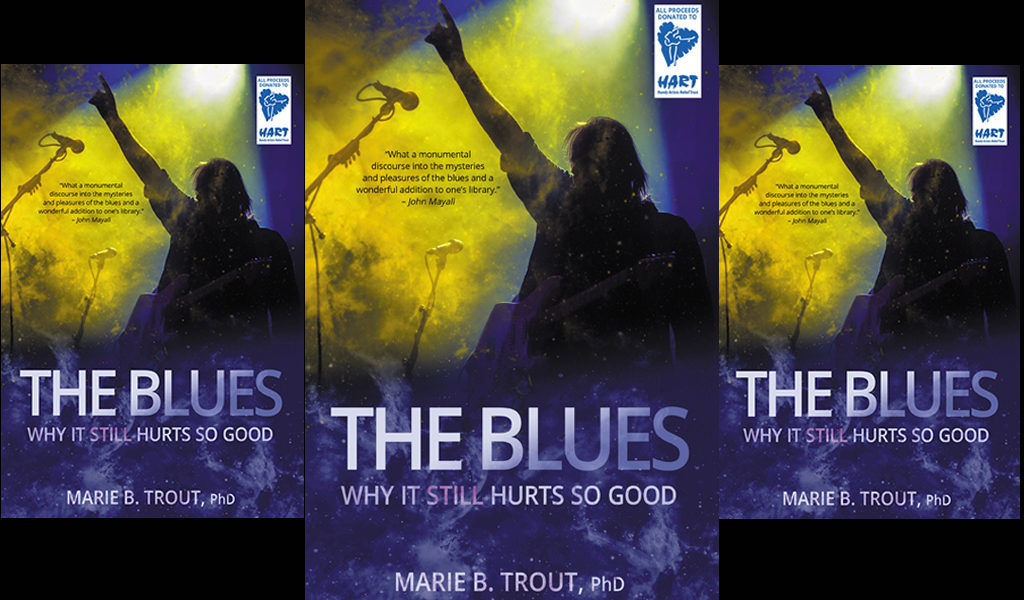

Today, Walter is thriving. Marie, who had had to put her own goals on hold caring for Walter, has been working towards her own discoveries and accomplishments. Based on her Ph.D. dissertation she has written, The Blues – Why It Hurts So Good, due out February 3rd, with all proceeds going to the Blues Foundation’s HART Fund. As stated on the Blues Foundation’s website: “The Blues Foundation established the HART Fund (Handy Artists Relief Trust) for Blues musicians and their families in financial need due to a broad range of health concerns. The Fund provides for acute, chronic and preventive medical and dental care as well as funeral and burial expenses.”

American Blues Scene was able to spend some time speaking with Marie about the book, why she wrote it, the research process, and what she has learned about the joy of the blues.

Barry Kerzner for American Blues Scene:

Why write this book?

Marie Trout:

You know I’ve worked with Walter for a quarter century now, and I have run into so many people who have told me many amazing stories about their life with the blues, who were not musicians. I couldn’t find a good outlet anywhere where this had been explored. Whether as a book, as a study, or anything that really went into what it is blues fans get out of this music.

There’s a lot of blues biographies, but there’s almost a sense that blues has lost its relevance because it is not part of a social and cultural movement that is oppressed or marginalized. The fact is that blues fans today are mostly white baby boomers … There is sometimes even an overbearing attitude that blues today is about garden parties and country clubbers and people who don’t really need this music.

My experience was counter to that viewpoint: ‘Yes, they need this music, based on the stories that they are telling me. They may not be oppressed and marginalized, but that doesn’t mean that they don’t get something profoundly important out of this music.’ That’s what I wanted to explore.

So basically, it’s about what fans are getting out of blues?

Yes – and looking at that is also to honor it. It’s to look at how it both can be serious and fun, and how it also can give us permission to accept that it is ok to feel when we are in the blues. It’s to honor our need for these experiences, and how able this music is as at providing it. Through that, also an understanding of why it is we revere and honor blues originators, the people who created this music.

They gave a gift that was much, much greater than I think we sometimes even understand and give it credit for. We honor them and their lives, and their contributions and their art, but the lasting legacy of what blues originators gave to us and our society is a continual benefit that we all have in our lives when we enjoy blues music.

On page 4 you write, “It has become clear to me that the blues fills needs that our current culture doesn’t.”

One of the things that struck me when I started surveying and interviewing these rather large amounts of blues fans, over a thousand of them filtered through, was how unhappy, no- that’s a strong word, how discontent they were. The vast majority expressed a feeling of disenfranchisement with “the way things are today.” Their statements often centered on feeling isolated or isolated from the mainstream culture, or what was going on in American culture as such. A sense of alienation almost.

They are just feeling like our world, our culture is bland. They lack connection. They lack something real. They lack latching on to a sense of meaningfulness. They find the political process pretty crazy … they feel that they spin their wheels, but they do not feel that they connect to the track.

They long to connect to other people in a way that feels meaningful to them.

You also write, “We celebrate the few times we manage to reach beyond the small, current audience of the blues today, but honestly—we rarely succeed. And how do we change that? How do we help others discover the transformative power of the blues when it is so difficult to even explain what it is?”

Many blues fans stated that they were filled up with awe at what this music gave to them personally, but felt it frustrating that they couldn’t quite communicate that to friends and family, and people they wanted to take out to concerts. They couldn’t really explain what this music did for them, much as they tried. Others just didn’t get it, and it was frustrating to blues fans that people with other musical tastes don’t seem to connect to it; they don’t really perceive it.

So I found that, for many blues fans, what had bowled them over was a time in their lives where a blues song spoke to something very deep inside of them. Whatever the story was, blues had come in and affected them. Or the music had simply gotten under their skin, and started a curiosity, and that curiosity then had led them to other types of blues music, that would then go back in time toward the originators, towards where the blues had originated from.

Each time they dug deeper into their relationship with blues music, their own story expanded along with the story of the blues because they now had a historical insight that was coupled with music that gave an emotional personal insight and experience.

So, each time it got bigger for them, it connected them, and it also became more important to try and tell that to others because it was such a transformative experience for them.

So everyone has their own story about how and why the blues experience is meaningful for them?

You can say that, yes. It is one of the reasons that it can get so unpleasant when we discuss what good blues ‘is.’ One person’s opinion can cut someone else’s priceless experience.

What I ended up compiling out of all of this was when we tell our blues story, everybody has a blues story of their own. It’s some moment in time where blues comes in and does something. When we tell those stories and how they affected us—and continue to do— we are telling something that is also bigger than the music itself. The music becomes a vessel for the experience.

In that story telling there might be something that can connect your friends and family, and otherwise uninterested people in blues music to kind of check it out. Because now, they have a vicarious emotional access point to what you’re getting out of it.

It’s not so much about what blues music is, as about what blues music does, that I have focused on. It’s there that I think is something that we hadn’t really explored, and it is also there that it does something that’s remarkable. But we have to get beyond the endless discussions about what is ‘good’ and what is not.

Basically, the experience everyone has, and how it affects them, and why it affects them in a certain way, is what you have looked at.

Right. And I wanted to speak to a representative sample of “regular” blues fans. They were randomly chosen because I wanted to get a snapshot of what’s going on out there on the ground level of blues enjoyment. It surprised me how many of these had remarkable stories to tell about the blues.

In chapter 19 you explore the “Healing Potential of Blues.” In the section, ‘Situation-Specific Healing’ you write, “Of course, blues is first and foremost music, not medicine. But blues music does contain elements that are restorative, soothing, and healing under certain circumstances.”

I found it interesting that the blues boomers (as I called them) often found it difficult to state ‘What is happiness? Where are we looking for contentment, safety, and relief? White baby boomers, particularly men, are, by the way, the fastest growing segment of users of opioid analgesics. So, pain numbing is in high demand. That’s not just knee or back pain. There’s something else going on, and that emotional pain we experience is often diffuse and difficult to describe.

As I talked with fans and laid their stories over each other, it was clear that there was a lot of need to express this “thing” that was down in there and that blues did that for many blues fans. While it is comfortable short-term to numb (and that is certainly often the cultural solution we are given) when emotions are expressed in blues music, it is such a relief to be able to let go of some of that, and feel that it’s OK to feel it. Others feel it too. We are not alone in feeling broken, lost, or conversely have a need to let go, listen to loud music, have fun and let ‘er rip!

One of the most moving things for me doing this work was to unpack the therapeutic effect of this music, and how it helps us find peace with what we otherwise might have a hard time finding words to even express.

For me, it felt like sacred work to be allowed into this universe that felt like not a lot of people were let into. People were really talking with their guard down. That was such an honor.

I’m an artistic, creative person, and without music, I would have been locked away in a rubber room.

And I heard so many say that! It was quite common. ‘If it weren’t for this music, I’d be on Prozac.’ ‘If it weren’t for this music, I’d be dead, quite honestly.’ I mean people said that you know? So it was clear that this is earth shattering, life transforming, lifesaving, sanity supporting, music. Even today.

The music has a different entry point and meaning to its current audience for different reasons than the originators, but when all is said and done, we are all bonded in experience. That is tremendously important. That music bonds us, and hearing about other people’s experiences and resonating with them is more important to focus on than our divisions.

On page 256 there’s talk about how musicians experience a sense of timelessness, and let themselves go in the music.

What came back to me from fans was, they know when musicians loose themselves. The most descriptive comments were along the lines that ‘the musicians click with each other. Something clicks onstage. When they start to click, I click with that experience.’ If I translate what they experienced at those times, it was often a sense of timelessness, or losing one’s self. Some called it spiritual, and some didn’t.

However they described it, it was a similar experience that musicians describe that they experience when they’re up there. All of a sudden they lose themselves and they might feel that the instrument plays them, rather than them playing the instrument. It’s a sense that you are a channel for something that’s coming through you.

Here’s a cultural observation I think is important, that ties in with our thinking that we have to be influenced by some substance to reach that altered state of consciousness where it flows through us. I think that’s one of the cultural things that’s been slammed into us.

So, the only way we were culturally allowed to let go of ourselves, is through a substance. Then, the substance does it for us. We are ‘given permission’ because it isn’t really us.

The beauty of this music is it allows entry into the place, both individually, but also collectively when we are in a group and we click with the music, and the musicians click with the music, and we click with the musicians, and so on. We feel each other. We feel that field of experience, and it’s OK. It’s OK if we look a little silly, shed a tear, or our belly fat wiggles. We don’t have to be drunk to let go. So it is this forgiving place.

Again, a great legacy and thank you goes back to blues creators and originators, who felt the music, showed it in their face. They showed their agony. They showed their joy. Through watching and hearing them, we learned, and as a culture kind of got permission to get lost in that field ourselves.

When fans wanted to describe what it was about blues music that could bring about an almost spiritual experience, their language to describe it varied. Basically, the various ways they would describe being overcome and in the moment. What about them being in the moment and them being able to let go of all the stress and external ‘distractions’ as you put it?

Yeah. It was interesting because blues music allows access into those realms, whatever we want to call them, through the body. This isn’t something that necessarily happens when we think about it, or go to the head place. It happens when we let go of that head place, and really just become very ‘present.’

For musicians typically, it’s complete immersion into the groove that speaks; a musical language that is not exact. You are a little bit offset, so you can’t really think your way into it, you have to feel your way into it. You let go of the ‘busy mind’ and just feel.

What stood out was that fans talked about it, which is really where the perspective is here … because I’ve always heard about the groove from musicians. Of course, it’s a qualifying feature of blues musicians playing together.

For the fans, it’s a release.

So, I wasn’t sure how much the fans were hip to that. Whether they called it groove or not, they were extremely aware of that quality. Although some of these fans were not musician type fans at all, they still described the feeling: ‘It is what happens to my body when the music gets real. It happens in my body, and all of a sudden I can’t stand still.’ And that’s certainly a part of the groove. It’s something that fans really responded to as a central feature to them, and one of the things that distinguished what was considered to them, really good blues music, from blues music that was OK. They could clearly feel and describe the difference.

That to me was essential in understanding the importance of those things that we can’t always describe. Another reason blues music is miraculous to me after doing the study, and really grew in my estimation, is it’s brilliance in allowing the unspoken, diffuse, and emotionally opaque to become experienced and cathartic.

Those experiences are absolutely precious. I believe that is a powerful antidote to a society of division. When we groove together, we are one. When we recognize that others feel like we do, we don’t feel so alone.

What else do you hope you have achieved with this book?

One of the things I hope also to give to the blues community with this book is legitimacy around … the 2 kinds of authenticity where there has been always this straitjacket around this concept of authenticity, meaning, “back to source,” or “original, pure,” so we go back to the originators. I call that ‘context specific authenticity,” in a certain particular context. Then you can talk to origin as “back to source”

But there’s another level of authenticity, which I call ‘universal authenticity,’ which is that which we commonly share, and we don’t have to be any particular context to know what that is like. We recognize pain, sorrow, joy, elation, etc. You can be an authentic blues player when you play from the heart. These two kinds of authenticity are not mutually exclusive, you just have to define what kind of authenticity you are talking about.

Anything else you want to add?

I am grateful to American Blues Scene for supporting this project from the get-go.

Thanks for taking time with us.

I really enjoyed it. Thank you!