This is the wild world of a Mississippi-Born Icon who paved his own path on music’s treacherous trail.

Daddy told me on his dying bed

Give up your heart but don’t you lose your head

You came along girl, what did I do?

Lost my heart and my head too

Little girl, little girl you sure can cook

Little girl, little girl you’ve got me hooked

When you cook that chicken save me the head

I should be working but I’m home in bed

Thinking about you Dreaming about you

Love that gal Love them chicken heads too

Without your love, I just cant go on

The feelings I have for you girl is much too strong

Let me in, Let me in, Let me ease on in…

I couldn’t shake Bobby Rush’s 1971 hit Chicken Heads out of my mind as I barreled down the Blues Highway 61 after my stay at the Shack Up Inn Bed and Beer in a shotgun sharecropper shack during the Sunflower River Blues and Gospel Fest.

As I passed the legendary crossroads of Highways 49 and 61 where Robert Johnson allegedly sold his soul to the Devil in exchange for mastery of the blues, I became increasingly excited, eagerly anticipating meeting the “King of the Chitlin’ Circuit, Bobby Rush.

It was a trip down Memory Lane, past Po’ Monkey’s juke joint in Merigold, through Shaw where my old friend, David “Honeyboy” Edwards was raised, stopped for gas in Leland where Johnny and Edgar Winter spent their younger years.

I saw the sign pointing to Belzoni, “Catfish Capital of the World,” where Pinetop Perkins was born on a plantation. Just as I was rolling into Rolling Fork, my phone rang as I was bellowing like a barnyard calf, “Let me ease on in,” and … Be still my heart… the legend himself was confirming that we were meeting in the Walmart parking lot in Flowood, just northeast of Jackson.

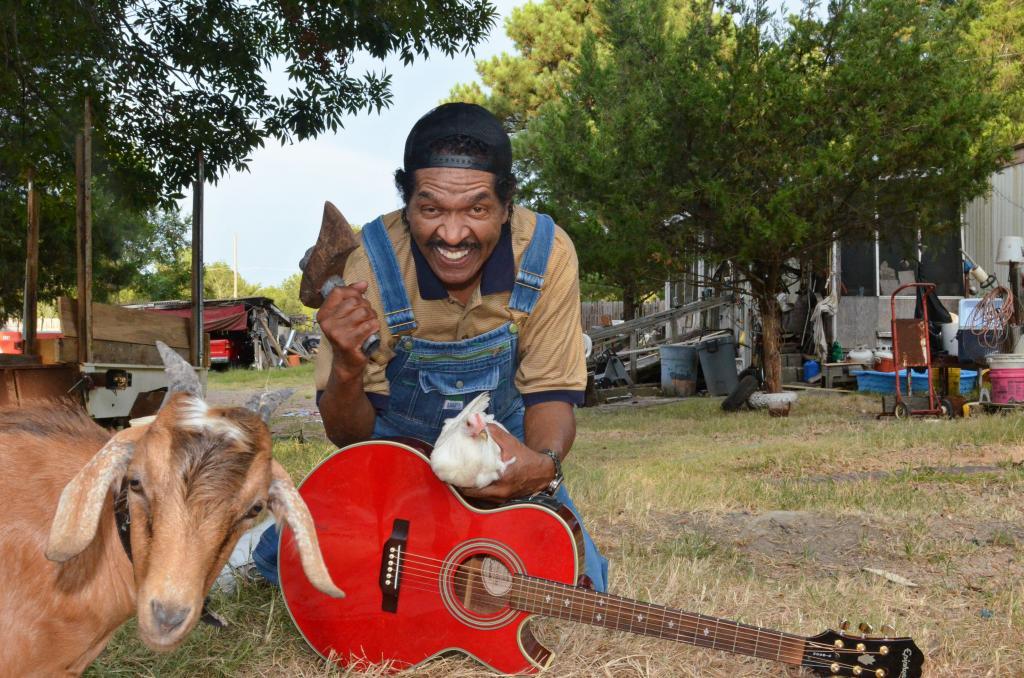

There, I met Bobby and his friend and driver for 27 years, Reuben, who would lead us out to the “chicken farm” somewhere in the middle of nowhere. When we arrived, the 102-year-old shirtless farmer named Wes came out of his farmhouse, which was a ramshackle old trailer, and greeted us warmly. Today was his day, since he had never been out of Mississippi, to a festival or any music performance, and here he was chosen by a legend he had never seen…

…but he had certainly heard about his scandalous shows with those dancing girls. His “farmhouse” was the epitome of abject poverty with missing windows, a tumbledown porch addition, and stuff everywhere. He had a small herd of goats and maybe a dozen chickens. It was like a train wreck that you couldn’t stop looking at. But Wes smiled broadly and seemed delighted.

When we told him about the pictures we hoped to take of Bobby holding a chicken and an axe, Wes became worried that Bobby was really going to cut his chicken’s head off. We assured him that no animals would be harmed and he relaxed and caught his prettiest hen for Bobby to hold. Neighbors began to come over; news spreads fast in the woods and everyone wanted to shake his hand. A young man rode by on a quarter horse, waving and smiling.

Afterwards, Bobby asked me if I would like to “get a bite to eat” and suggested Chick-Fil-A back in Flowood. When we sauntered in, laughing because I accused him of being too kind-hearted to kill that chicken so now we had to buy some, the cashiers all gawked at us and in three-part harmony said, “Bobby Rush!”

The manager came out to see what the scuffle was all about and she exclaimed, “Oh my Lord!” A flurry of photos ensued with calls to friends and husbands about the biggest celebrity to hit Flowood in years. I began to wonder if we could really carry on a conversation here without constant interruption, but we decided to give it a shot.

So, we settled into a booth. As you may imagine, Bobby is quite affable, humble, and sincere, so we chatted like old friends. He said, “I sure am blessed they sent you to take these pictures. The heaviest picture you ever took may have been today with me at 82, with a background of a man of 102 who doesn’t have a change of drawers but he has richness in his heart and he’s at peace with himself.” “No, many wealthy folks aren’t at peace with themselves; that’s priceless,” I agreed. He nodded confidently. “Just show those pictures; they say a million words. There is great meaning in those pictures to me. Others may not understand it, but I call the shots. Until I die, I’m gonna call the shots. This farm reminds me of where I came from, what I relate to, and the people I associated with.

“We didn’t know we was poor because all of us had the same thing, which was nothing, but we had a lot of love. That farm sums up my life from the beginning. Here’s a guy who is 102 years old, never been out of Mississippi, just to the store and back home. It’s touching to me.”

“I’m one of the most blessed men who ever lived; let me tell you why. My Dad had a dark complexion and my mom, Maddie, had blue eyes and blond hair and she was built. She could be white when she wanted to be, so when we were out in company, she was “babysitting” us ten children. One day, two guys came up on horseback and asked her, “What are you doing with those niggers?”

She said, “I’m one too.” They didn’t believe her so they followed her into the store. Mr. Ben, the storeowner, said, “Yes, she’s one of Van Spivey’s kids.” They got on their horses and left because they respected my grandfather.

“Ya see, I didn’t know anything about white and black issues when I was a kid. My daddy was the biggest traveling pastor in the area. Everybody in my school including the teachers was black. I didn’t have to work for nobody but my daddy workin’ the cotton fields from sun up to sun down. There were twelve people in my granddaddy’s house who lived to be over 100 years old.”

Yes, indeed, he has some good genes; I swear he looks like he could be 60. He wouldn’t share with me where he found that damn Fountain of Youth, but I suspect that it’s in the Mississippi Delta and not in Florida as Ponce de León thought. I asked him if he still does those age-defying splits onstage these days. He smiled, “I’m an active person but I don’t do those splits on stage much anymore. You live and you learn and I must learn what I cannot do because what I can do takes care of itself.”

I asked him how blues had changed since he began 55 years ago and what he thought was the future of the blues.

“There’s no difference in blues from the past to present. It’s just that the writers, festival producers, and most club owners who hire musicians have put it in the black blues player’s mind that the blues were something less than other music until the white blues players raised it up. Then they wonder why black people don’t come to the festival or show. Now they have more locals instead of headliners like me who can put butts in the seats.”

“The future is gonna be brighter than it ever was before but it’s gonna come because of the white guys playin music and then the black guys gonna try to grab and hang onto it. I’m proud of ‘Kingfish;’ he’s good for 16. The Peterson Brothers are equally good but they gettin’ to the age where the pressure is off of ‘em. Like all fat black ladies are supposed to sing good.”

When asked how he was able to climb up to the top on his own without a manager or anyone, he looked up and leaned back in the booth. “It just sneaked up on me. I wrote until I found someone to write, I managed my self until I found someone to manage me. Over 40 years slipped by. I found out that I was the man for the job.

“Elmore James and Muddy Waters loved to be around me in the early 50’s and I thought of them as old guys; they were in their 30’s! Muddy invited me to Chicago to a birthday party at Silvio’s on Lake Street. I walked in the door and Muddy said, “Blood, we been waitin’ on you.” We went upstairs, there were these old ladies in their 30’s with dresses up to here. I ran out the back door!”

His incredible talents have earned him multiple Blues Music Awards including Soul Blues Album of the Year, Acoustic Album of the Year, and, almost perennially, Soul Blues Male Artist of the Year. (Editor’s Note: And a Grammy Award)

“I went to work a swing club on Bourbon Street and on the door it said, ‘No Coloreds Allowed’ but I got a job there. I walked in with my band of four white guys for the audition on Bourbon Street and this Chinese guy named Kunch said they were gonna integrate the place, but I didn’t know what integrate meant; I had never heard the word.

So we show up the next night with my black band and we wait out in the van until five minutes before the gig so they can’t fire us. The manager asked where the band was and I told him this is the band. “My God, they’re gonna kill me,” he said.

So they got me up there on the stage with my guitar and they acted like they never seen a black man before. After that, I got called to the office, and the man smokin’ a big stogie said, (Bobby changes to his best mafioso impersonation, like a black Marlon Brando) Hey you, kid! You integrate my place! You scared of me? I shook my head, no. We gonna make a lot of money. This kid is my kid, ok, Kunch? He got nerve to come in here and integrate my place. I pay him. He good kid. He stuck a card in my pocket and said to call him if I needed anything.

I tried to break away and find another gig, and someone offered me a raise in a black swing club. When I went to get my check, they directed me up to the office where I was before, right back to Caesar Capone! Honest to God, I didn’t know about the Capones and he knew it. He let me go down the street to get a raise…from him! I hired Freddie King, Elmore James, Redd Foxx, Sammy Davis, Jr. and whoever he wanted. He was good to me and that helped me on the business side but it hurt me on the recording side because I lived so comfortably and was makin’ more money than Elmore and them; I was makin’ $75 a night in 1952 and bought a house when I turned 21. But they was cuttin’ records and makin’ a name for themselves.”

When asked who inspired him, he told me, “I was inspired by a lot of artists. I liked Louis Jordan because he wrote so well about what I related to like Saturday night fish fries, Choo Choo Ch’Boogie, Is You Is or Is You Ain’t My Baby, Ain’t Nobody Here But Us Chickens, and a song about a monkey and a buzzard that got me thinkin’ about animals, which led to my first big record, Chicken Heads.

I liked Ray Charles ‘cause of the way he played, Muddy Waters ‘cause he dressed so dap, Sonny Boy Williamson because he sung so well, Howlin’ Wolf ‘cause he had a different voice, and Little Walter ‘cause he was so swift with his harmonica playin’. I loved and respected B.B. King and I’m flattered that Buddy Guy does Chicken Heads in his show and he is a good friend. B.B. asked me to play his last show with him in Memphis. I was headlining a festival and the promoter let me play early so I could go. I got B.B. King’s Entertainer Award and he died six days later.

I was sitting at the table and B.B. called me up to the stage and he sang “Ain’t No Sunshine.” That’s touching; that was the last time I saw him. He passed the torch to me, but it didn’t hit me until his funeral. I cried like a baby. People tell me you are the next King of the Blues. But I say I’m Bobby Rush, I’m just doin’ my thing! If I’m not the oldest bluesman, I’m close to it, between Buddy Guy and myself. The next main ones close to my age are Fats Domino and Chuck Berry, but they don’t call themselves bluesmen yet we all are friends and in the same business.”

“The first song I ever fell in love with was a country western tune that I heard on a popular nighttime radio station, WLAC out of Nashville. I don’t even know who did it.” He began to croon, “You get a hook and I’ll get a pole, we’ll go down to the crawdad hole, honey baby, baby.”

“There was a young black man who introduced me to two brothers, Leonard and Phil Chess of Chess Records. The Musician’s Union had two divisions, 208 and 210, one for black musicians and one for white musicians. We didn’t get the same support that the white musicians got. I saw a card that said the two unions were merging and I told the guys doing a session there, “This is gonna be good for us, man!” Muddy Waters, Little Walter, Willie Dixon, Lightnin’ Slim, Smokey Hogg, and Pinetop Perkins were all there. Everybody looked at me like I shouldn’t say that in front of Bill and Leonard. So Leonard asked Bill, “Where did that boy get that? We can’t hire that nigger because he can read.” “Goddamn!” just erupted from my mouth in response, perhaps a tad too loud and a bit inappropriate for family dining. Ooops! But damn that stung!

I had seen Bobby perform many times at the King Biscuit. Though I love his big ace band with well endowed dancing girls and his risqué antics and shtick that is bigger than those 10XL panties, I really treasured and admired his classic raw solo sets on the acoustic stage with his guitar and harmonica. He truly shines there.

He nodded, “Yes, at the King Biscuit Fest, I do the acoustic stage every other year so the underprivileged folks can hear me too. I want to spread myself to people who don’t have the money for the big stage. Last time, I played on Thursday night so the old folks who don’t want to get caught up in the weekend rat race could come see me.

“I modified my music and approach; I electrified before it was popular. Most bluesmen are afraid of change, but I’m not. I’m tired of musicians cutting a record a certain way because they think it is what people will like. Just cut good music! How many guys do you know that have the nerve to drag two to four dancers onstage built like that?” Hmmm… I thought, I can’t think of anyone. In fact, I have never seen women who could move like that! They’ve got butt muscles that are larger than life. Looks like two piglets doing choreography in their tight lamé slacks.

“I’m excited about the new box set and I’m proud. It’s coming out around my 83rd birthday in November. I just hope that this set will tell the story of what I have done up to now and where I come from.”

His manager, Jeff DeLia, added, “Bobby Rush is a gem of a person, entertainer, songwriter, producer, arranger, artist, businessman, and friend. For me, working with him is a blessing and real treat; to be a part of this career-spanning release is an honor…

“The Bobby Rush boxed set, “Chicken Heads: A 50- Year History Of Bobby Rush,” is a really special release. It’s the first time in his career you will have all of his classics and most of his early recordings in one place. Song selections were carefully made to illustrate the best representation of his careers work. Bringing together hard-to-find early 45s right up through Deep Rush Records and his latest recordings, fans will get the classics like “Chicken Heads” and “I Ain’t Studdin Ya”, to “Let it All Hang Out” and “Hey Western Union Man” too.

“It’s hard for me to sum up Bobby Rush in a few words or for anyone to sum him up in one retrospective, but this collection brings together all shades of this legend’s 50+ year career, complete with never before seen pictures spanning five decades, tributes by his friends Mavis Staples, Leon Huff, Al Bell, Denise LaSalle, Benjamin Wright, Elvin Bishop, David Porter, Keb’ Mo’ plus notes from Bobby Rush himself. In addition, there are three previously unissued songs. One, a gospel song recorded with Al Green’s band, another, a country-western standard, and one in the classic Bobby Rush sound: southern soul/blues. All of these recordings demonstrate how inventive this legend has been throughout his career and even today at age 82. At this point, he is one of the last ones of that generation. This is a release all Bobby Rush fans should have in their collection, and any fan of American music… this is history.”

His box set is a tribute to his resilience and tenacity, a sign that the lessons Howlin’ Wolf and his peers learned and taught have been neither lost nor forgotten. It will enchant you with the delight of the evolution of Bobby Rush, while bringing you back to the core of your most basic emotions. It will be a heaping serving of soothing Chicken Heads soup for your inner soul.