It speaks volumes of an artist that he or she will enthusiastically and lovingly present music in a way that is at once new, bold, and refreshing, yet still, respects the traditions and roots from whence it came. It is even more remarkable when that music is born of a long lost art that isn’t dead by any means but does not enjoy the favor and recognition that was once showered upon it.

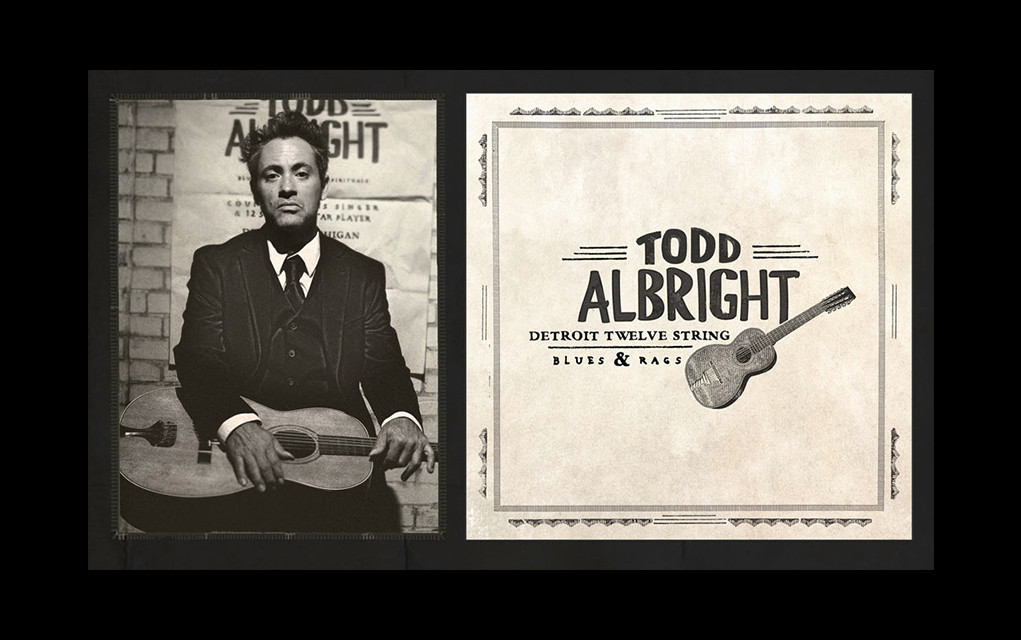

Todd Albright has studied both revered past masters of country and delta blues, as well as modern masters of these art forms and “folk” as well. Currently, he is a recording artist on Jack White’s Third Man Records label, and his latest release is the EP Detroit Twelve String Blues & Rags, a selection of acoustic 12 string performances that exhibit a mastery and passion seldom heard in this day and age.

Barry Kerzner for American Blues Scene:

There’s really not a lot out there in the wild on you.

Todd Albright:

No, there is not.

I like to do deep dive research on the artists I speak with because I really don’t want to waste anyone’s time, and…

This is a unique situation.

I know that you have been asked this before but for the benefit of our readers who might not be familiar with your story, tell us about when you were 12 and your sister gave you that John Lee Hooker record. What was that like for you?

I’m actually glad you asked this question because I’m not sure how that ended up in the bio. I think it was actually the Robert Johnson boxed set that came out in ’88 or ’89, whatever it was. It was the first thing I had seen or heard. I knew it was important then, but I couldn’t make sense of it at 12.

I hadn’t started playing guitar yet and I was playing harmonica at that point because the [Hohner] Marine Bands were fairly inexpensive. I think that’s where it started. I mean, it came out and it was everywhere! I was like ‘I don’t know what this is, but I want it.’ It might have been the photograph of him sitting there with the guitar. I don’t remember how I scrounged the money, but I did.

At first, listen it was like ‘I don’t know what this is.’ I knew it was really important though; there was a spookiness to it. a lot of his songs were like “If I Had Possession Over Judgement Day”… and it was kind of – terrifying. When you’re twelve and you’re in Catholic school… It was intriguing in the fact that it was kind of punk rock sounding.

Later, the John lee Hooker thing came in, but I was well into playing guitar at that point. When I started playing guitar, I was immediately attracted to anything that was finger-style. I would listen to anything that was fingerpicked. I didn’t care whether it was John Denver, Jim Croce; you name it.

Basically, whatever you could find?

There was something about the sound of a fingerpicked guitar. Then I was at the public library and I came across an album called Inside Dave Van Ronk. This has happened to me twice now. I took that LP home – the library still carried LPs then, and I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. That progressed to John Hammond, and immediately thereafter, Paul Geremia. I’ve been learning a lot from Paul for years and years. I was buying records on the strength of the cover art.

He was one of the first guys that came out of the country-folk revival during the ‘60s. He was a student of Reverend Gary Davis. Yeah, running into Dave’s record was an incredible thing because it was this big burly white guy, playing country blues.

Your bio says that you were “self-taught.” Besides the folks you’ve mentioned, is there anyone or anything else in particular that you learned from?

My mom’s cousin liked Hillbilly music and he was really big into Hank Williams and showed me my first couple of chords but, after that, there wasn’t too much further to go with that instruction. With playing guitar, once you become obsessed, you remain so.

Basically your goal or intent, and I’m quoting here, was to “interpret the sounds of the masters.” Could you elaborate a bit on that?

For me, it seems like the ’20s and ’30s were the golden age of guitar playing. As far as finger-style guitar playing, we’re talking about guys like Blind Willie Walker, or Reverend Gary Davis, who came out of the South Carolina area. finger-style guitar was the only way of playing guitar back then. It had multiple strings and you picked it.

I don’t know when flat-picking a guitar became a thing but, at the same time, it kind of became uninteresting. Strumming a guitar versus picking a guitar, I don’t know; it leaves a lot to be desired.

So, you’ve checked out the Mississippi Sheiks I’m sure?

Oh yeah! I’ve been well steeped in all of it! In fact, my whole world is country blues. Anything that was recorded until 1940 is my stuff.

What about Josh White?

Sure. Josh White was great. He was an incredible showman. He used, if not all five, four of his fingers to pick with. You don’t hear many people do it. His son, Josh White Jr. can do it, spot on like the old man, but I’ve never heard anybody be able to play in his style. And, who can sing like him? Just an incredible vocalist. The guy stood when he played, with his foot on a wooden chair. That’s how he performed. It was very sophisticated.

How about Big Joe Williams?

Big Joe? Big Joe was great! All the stuff he did in the ’30s; he had such a long career, for someone that was nicknamed “Hobo Joe.” He was incredible. The guy was the whole secretive shit where you add a couple of strings to the guitar and tune it in a strange way to throw off other players so they couldn’t copy you.

Your work covers George Carter, Blind Willie McTell, Leadbelly, Skip James, Sylvester Weaver and more.

Tell the folks at home a wee bit more about Sylvester Weaver won’t you? That’s not a name that comes up quite a bit.

I know, and it’s a shame too! That guy was the first person to ever record slide guitar.

Wow.

1926, I think it was on the Victor label, he recorded “Guitar Rag,” which was the first solo slide song ever recorded. What’s strange about him was that he had this great career; he was backing up, can’t remember her name, singer [Helen Humes], and he did sides later on, by himself singing and guitar. Then, he abruptly quit the music business and took on a job as a chauffeur for a wealthy family in Louisville, Kentucky.

He got married and had a family and nobody even knew he had a career in music, not even his wife. After he died, his wife found a scrapbook that he had kept that had every receipt, every bill for every recording, every detail of his entire career he kept in that scrapbook. So everything that we know about him comes from his own scrapbook. Incredible!

What upcoming albums or projects do you have where you’ll be covering some artists that you haven’t covered before?

I don’t have anything on the books yet because we are still working this one [Detroit Twelve String Blues & Rags]. The next record will be another outing of country blues on a twelve string guitar. It’s a difficult deal because there’s not a lot of songs that translate from a six-string to a twelve-string. And, vice versa. There are just some things that you can’t get away with on a six-string that you can do wonderfully on a twelve-string so you have to be really kind of choosy about what you decide to do. A six-string guitar and a twelve-string guitar; they’re just such different animals.

Absolutely.

It’s tuned excruciatingly low, and it’s got enormous strings on it; that’s what gives it that rumble.

You don’t ever tune down and then capo to take some tension off the top?

No. I mean, the guitar is tuned so low and so slack that it’s never gonna damage the guitar.

So you’re not in a normal tuning then?

No. I’m way, way slack tuned. A normal guitar is tuned to E and the heavy string is an E, and this is dropped way down to A. It’s super low. Willie McTell; it seems like the older he got, the lower his tunings became. Part of that was because back then, they didn’t really repair guitars, and when the action on the guitar got atrocious, he just bought a new one. He was known to buy a new guitar once a year.

So as soon as the action got shitty on the guitar, he just moved on to the next one. The lower the tuning, the more slack there is on the strings, the easier it is to play, but then you’re playing in a much lower pitch. So, that’s why a lot of his recordings are way low.

I think it’s amazing that you get such clear tone!

Well, you’re listening to a record full of it – that guitar is tuned to “A”. You have to understand something though. The lowest string on the guitar is, the gage of it is a .68. It’s super big.

Man!

The lightest string on there I think is .15 or .16. So, they’re super heavy strings which give it some tension where if you didn’t get that they’d be like rubber bands.

Let’s talk about your 2014 album, Folk Blues Night No. 9. That’s off the hook!

Yeah, that was cool; that was fun.

That one is somewhat hard to find. I did find it, and it was digital, and “name your price.”

The guy that did those didn’t make CDs; he only made cassettes, and he made the digital. You can download the digital version.

The other work I wanted to talk about is 2016’s Fourth Floor Visitor. So, if you want to talk about these two albums for a bit, that would be great. They are two different things.

The folk blues thing was a monthly happening in Hamtramck, Michigan in a record store called Lo and Behold Records. It was essentially a hootenanny type of thing. The only criteria were that you were playing acoustic and older music; anything that was in the folk blues realm. That was kind of started by Danny Kroha.

And the Fourth Floor Visitor?

I drove out to Minneapolis, Minnesota, where there was a guy named Dakota Dave Hull, who is probably the best living finger-style acoustic guitar player. There’s nothing Dave can’t do. His primary playing is Ragtime, and he’s absolutely amazing. He has a studio there in Minneapolis, and I’d become friends with him from playing gigs with him over the years. He was also friends with all the guys I knew like Roy Bookbinder, Paul Geremia, Dave Van Ronk; the elder masters of the folk revival of the ’60s. He was a little younger than most of those guys and he was stuck in the middle of North Dakota.

I went to his place and we recorded it in 2015. It got passed around a bit and I couldn’t get any bites on it. I was approached by a Detroit label, Jet Plastic Recordings and they were real excited about it. They wanted to put it out and I was happy to do it. It came out just a few months before the Third Man record.

Part two of this conversation with Todd Albright is just around the corner…