In 1969, the groundbreaking film Easy Rider‘s tagline of “A man went looking for America and couldn’t find it anywhere” was the summation of the tumultuous journey of self-discovery and disaffection experienced by multiple generations of Americans.

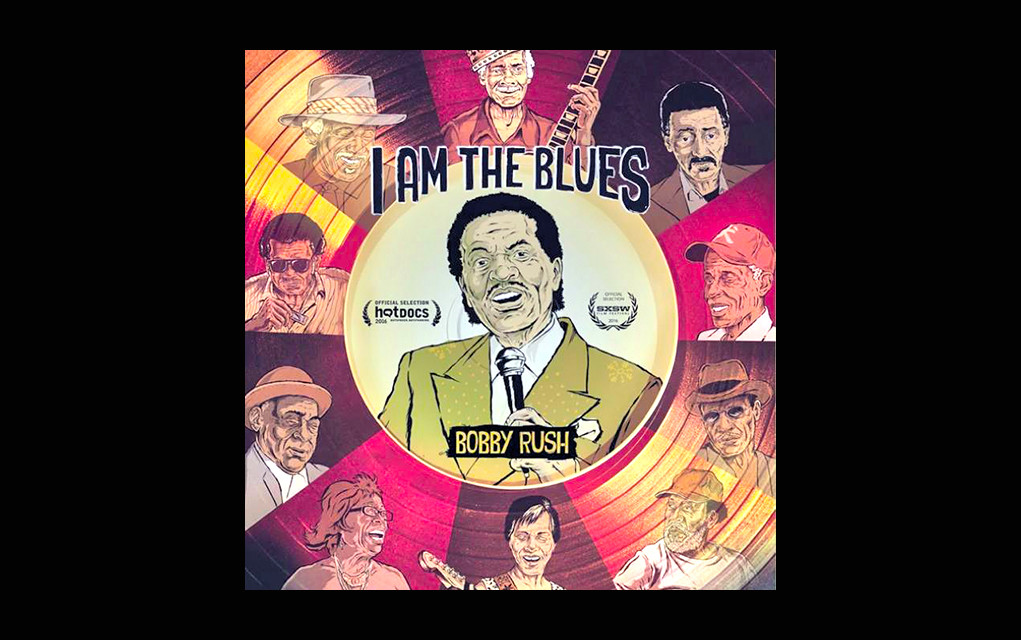

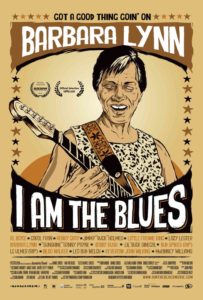

Director Daniel Cross’ film I Am the Blues is a musical and spiritual journey of discovering the blues of the Mississippi Delta and Hill Country, as well as the Louisiana Bayou. This is a journey into a lost hey day of great icons of the blues that were standard bearers for several generations that followed. These were folks that sang about the life they and their families lived throughout the South. This was a hard life of sharecropping, farming, picking cotton, with an ever-present helping of segregation and extreme prejudice added to the mix. These hardships permeated every aspect of life.

As Easy Rider looked at the changing face of America and what had been cast aside, I Am the Blues celebrates what remains of what had once been the face of the blues in the South. This is a journey that celebrates those who are still with us and are able to provide us a window into their music and the lives they have lived through their music and their stories shared.

As a director and a blues lover, providing an informative, coherent documentation of travels throughout the journey provided quite a challenge, as Cross confirms. After watching a review and being taken “back to my experience in the ’70s I thought, ‘This is it, this is my opportunity. I have to film old blues musicians living in the South.’ So I contacted Dr. Ike and he agreed to help me because I was in Canada without access and any familiarity to people. He agreed to drive me around. He’s an anesthesiologist at the New Orleans Trauma Center; a real doctor and surgeon.”

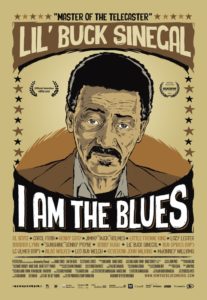

Dr. Ike, real name Ira Padnos, is the de facto man behind the Ponderosa Stomp (and the Foundation as well), which takes place the first weekend of every October. “Thursday through Sunday they put together a line-up and Lil’ Buck Sinegal tends to provide the house band. They put on a review on Friday and Saturday night. During the day on Thursday and Friday they hold a conference, and there’s panels and discussions regarding stuff of musical historical relevance. Billy Boy Arnold was there the last time. Over the years, everyone has kind of gone through there, and a lot of them have reignited their careers through the attention that the Ponderosa Stomp and its foundation have given them.

“These musicians love Dr. Ike; it was not just like me showing up and me asking for a favor. We would literally be driving and he’d say, ‘Oh. McComb, where Little Freddie King is from. Let me give him a call.’ So he’d call him on the cell and let him know we were pulling into town and we would be stopping by. That’s how I met them.”

It was through Dr. Ike that Cross met Bobby Rush, who would prove invaluable in capitalizing on opportunities that presented themselves for encounters and performances that otherwise might not have taken place at all. Cross explains, “He told me that ‘Beginning in July, I have ten days that I can take you around. Be at this corner at ten in the morning and I’ll pick you up.’ He was there and we went all through Mississippi. He introduced me to like, 30 different blues musicians of varying fame and fortune. We started with Allen Toussaint in New Orleans, and Little Freddie King. We ended up at Jackson, where I met Bobby Rush.

“When I met Bobby Rush, that was a big change because he was very gracious with us and I knew who he was, so there was name recognition. So the first time around, all I did was interview them and talk with them. We filmed it and that was to basically see who had charisma, good story telling, and was still kind of adroit and nimble, and would be an active part of the film.

“Some of the musicians were clearly not interested. Bobby Rush took me aside and said, ‘Hey, I’m Bobby Rush. If you wanna make this happen, I can help you make this happen. I respect what you are trying to do. You’re trying to tell the story of a lot of the long forgotten pioneers and I’ll go with you when I can, and my presence will be helpful because I’m familiar and they’re my friends and I can talk to them in a way that you can’t.’ And he did.”

Bobby Rush acts as a de facto guide which is great for everyone concerned. After all, he is Bobby Rush, as he explains in the film: “My name is Emmett Ellis [Jr.]. I changed my name to Bobby Rush and I said ‘Oh, that sounds good because it sounds like one syllable.’ Nobody call me Bobby. Nobody call me Rush. Everybody call me Bobby Rush.”

So, between Dr. Ike and Bobby Rush, Cross was able to meet a host of blues greats that he otherwise would have never found, much less meet with them and/or see them perform. “Yeah, it was very nice. For me it was like a dream come true. My problem was that I met like, 50 musicians, and there’s no way you can make a narrative; you can make little vignettes, but you can’t make a narrative with all these musicians. So, I had to figure out who I would focus more on, and how I could make a story out of it.

“He [Dr. Ike] has a genius brain, so he remembers everyone’s phone number by heart. Wherever we are, he just dials their number and tells them we’re here, we’re dropping by. He’s like a human rolodex; very helpful!” Even Cross has to laugh as he shares this observation with us.

When he is asked how hard it was to bring everything together, and if in the end he accomplished what he wanted, Cross thinks for a bit and tells us, “When we were going from place to place, I was a little worried because we were skipping along and hitting so many different spots. We didn’t stay very long. I was excited and I wanted to meet everybody. So when I had done the first trip, I was like, ‘Oh my God! What do I have?’ It was just little clips of random moments, and I didn’t know if I was going to be able to go back and hang out more.

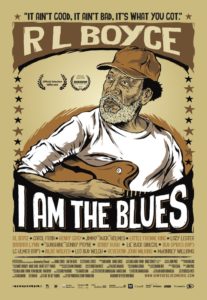

“What happened is when we ended up in Como, in the hill country, we had a moment where we met RL Boyce, and that was a big turning point for me. Actually there were two big turning points, the other one being the Bobby Rush one I mentioned. RL took me around and he showed me a good time. I thought that with the right amount of patience, I’ll get these people up and out like they’re full of fire, piss, and vinegar, and good stories. It helped me believe that these were characters with an unbelievable amount of charisma and history in the stories that they have to tell. It really encouraged me and re-energized me.”

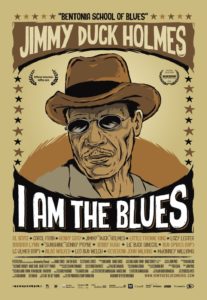

Cross continues, “So the next time I went, Dr. Ike wanted me to go the Lafayette way, and I said I wanted to go the Mississippi way again because I knew I needed to cull this down. I needed to visit some of the same people and get to a second stage of friendship and documenting with them. One of the key points was the Blue Front Café; it was like a clubhouse.

“Most of them are really poor. They live in really small, old houses and they are packed with belongings everywhere. We were trying to film and you were tripping and you can’t stand back. You need to get them out and about, with other people so that there is more than just someone sitting on a couch.”

In the movie, Rush speaks of early on going from getting a gig and getting paid with sandwiches to eventually getting hamburgers to getting enough hamburgers to eat and still be able to sell the “surplus.” He finishes with, “The Chitlin Circuit was no joke!”

Listening to the stories and music at various stops along the way, coupled with glimpses of these towns (including backstreets and farms), lends an understated fullness and understanding to the whole experience.

As Cross says, while even locating some of these artists was a huge endeavor, equally daunting was trying to have these musicians participate in presenting their music and basically, “come alive.”

“With Ira, I told him I didn’t want to work with management, I just wanted to meet the people on the porch step and go from there. I was reading magazines and looking on the internet, and half the people, you don’t even encounter their names. He had that first person relationship with them and when we ended up at the Blue Front Café, it became very clear that this was a place that we could build on. Jackson is only 30 miles that way. Let’s get to know Jimmy “Duck” Holmes a lot better; hang out for the Bentonia Blues Festival. I have to spend my time differently. We started to put together the idea, we’ll bring the musicians here and relive the old times.

“When they get there, they are happy to be there and they all know each other anyway, so we just let stuff happen. Basically, they’re all showing off to each other.

“We did the same thing in Lafayette around Lil’ Buck. Lil’ Buck is a consummate musician and most of them are front men and front women, so they don’t really have the band part. Put them in front of a band and they will take over. What they have lost in their life is a good band. So Buck runs the band, he plays for everybody, and he’s really good. He’s like this gold around them.”

When asked what is the legacy that these artists leave for us, and what do they have to say to the younger people that are just discovering blues, Cross lays out an interesting perspective. “Every one of them is in a blues and/or a state hall of fame. Carol Fran has the National Medal of Honor, and Barbara Lynn was number one on Billboard several times, and Willie Cox as well. Every one of them lost their career, except for Bobby Rush, at some point in the late ’70s, hitting that middle age point where they had to decide how they were going to support their families. I would say that they were true victims of racial prejudice that prevented their talent from being completely celebrated or even exploited, popularity- wise and economically.

“Guys like Little Freddie King became lumberjacks and farmers and just went back home. Barbara Lynn just went back home and took care of her mom. They pretty much stopped trying, and then later when we lost some off those “A-liners” and experience, we realized that they are the true roots of the blues. They have lived the life, coming from farms and cotton fields, and have that experience.

“Robert Bilbo Walker’s family picked 200 pounds of cotton every day as sharecroppers. So when you hear their blues played, they can’t be the blues like Tommy Castro can play, or Popa Chubby. They just don’t have that first-hand life experience.

“Everyone has a particular first-hand life experience but this particular segregated, sharecropping, slavery-type experience ends at that generation. Then it becomes a different generation of experience. The fact that they’re playing live today makes them national treasures that we need to almost pilgrimage to listen to and get to experience, if only for that experience.

“More important than that is the positive energy and attitude they have on life. The love that they have for each other, for people that are willing or able to care for them, is so moving. My life was so changed by getting to know these people.”

This movie should not be missed. It is a gift on so many levels. The fact that we can enjoy performances, however brief, by Bobby Rush, Henry Gray, Barbara Lynn, Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, Little Freddie King, Robert Bilbo Walker, the late LC Ulmer and more is in itself priceless. Then there are the street scenes, the landscapes passing by as we travel through the Mississippi Delta, Hill Country, and more. And of course, there are the stories and insights that the artists themselves convey to us. In all, this is an invaluable glimpse into the past, and a living record of the blues as it was, and as these greats lived it.

I Am the Blues

Directed by Daniel Cross

Produced by Bob Moore, Daniel Cross

Cinematography by John Price

Edited by Ryan Mullins

Screenplay by Daniel Cross, Marco Luna

Opening July 12th at Quad Cinema

34 W. 13th Street New York

Director in attendance for Q&A

Wednesday July 12th & Thursday July 13th at 7pm