Have you ever wondered what it would be like being a witness to history? While we all are witnessing history every day, what if you were there when Robert Johnson recorded the sides that still to this day are the very foundation for much of the blues and rock and roll? What if you were there at Carnegie Hall that cold January evening in 1938 when Benny Goodman and company brought jazz into the mainstream and it became “respectable”? What if you were there when Muddy Waters first plugged in?

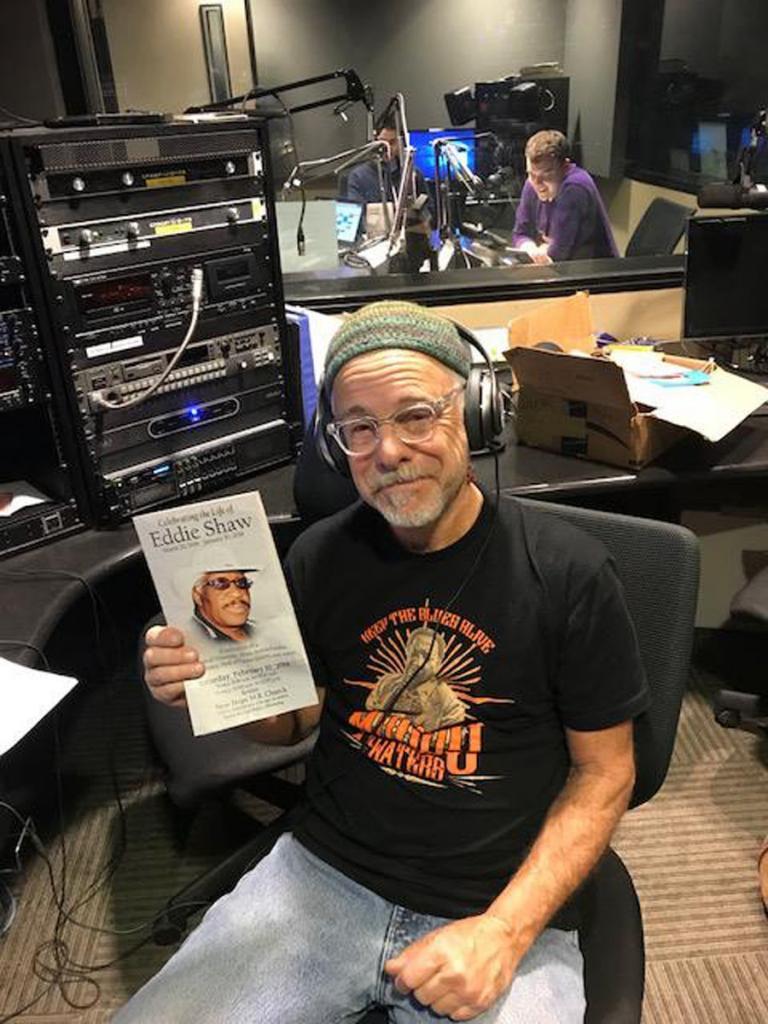

Terry Abrahamson is just such a witness. Thankfully, he has been gracious and articulate in sharing that history with those that were not there so that it is preserved and passed on.

Terry is a composer, author, playwright, photographer, historian, and more. He is a perfect example of Shakespeare’s assessment, “And one man in his time plays many parts.” He won a Grammy Award writing tunes for Muddy Waters and helped George Thorogood get his career off the ground and established. He made a Levis commercial with none other than John Lee Hooker. His songs have been recorded by John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, George Thorogood and more.

His book, In The Belly of The Blues is a staple in the blues and rock communities and continues to do well. But Terry is not very good at standing still. Currently he is looking for a publisher for his recently completed kids’ book, The Blues Parade and revising his play, “Doo Lister’s Blues,” about the conspiracy to suppress political content in Black pop music in the 1960’s, for a Fall 2018 Los Angeles production.

He and his songwriting partner Derrick Procell continue creating work for artists including Duece ’n a Quarter who recorded “Rear View Mirror” on their new album of the same name. Shemekia Copeland’s upcoming album America’s Child includes “In The Blood of The Blues,” also written with Procell. Other songs written with Procell awaiting upcoming release include “A Tall Glass of You,” “A Lotta Man” and “Like You Make Love” by Nellie Tiger Travis, and “Oily in the Morning” by Oscar Wilson. “Let’s Play Chess” and “Mississippi Found Me” by Joseph “Mojo” Morganfield round out the pair’s new work.

We caught up with Terry recently and talked about being young and writing for and traveling with Muddy Waters and his band, his bird’s eye view of history unfolding, and why he loves the blues.

Barry Kerzner for American Blues Scene:

I’ve been so looking forward to having you share your perspectives with us. All the things that you have seen and been part of in the course of blues history.

Terry Abrahamson:

What I was a fan with a camera. Back in those days nobody carried them, let alone a phone that would take pictures. I had the camera and I took the pictures cause I’m a fan. I’m a fan just like you are.

What was it like to travel with Muddy Waters, to write with Muddy Waters?

I was young – I was in my early 20s. When I met Muddy, I was 18 and it was surreal. I got swept up in it and never really had the chance to do it with any perspective at that time. I didn’t really appreciate it back when it was happening like I do now. Corky Siegel has a quote which I probably refer to several times a week; always in discussions about this stuff. Corky said, “We knew it was cool; We just didn’t know how cool it was.”

Muddy was always this larger than life character to just about everyone that knew him. It was no different for me. Going back to when I first wrote the songs for him, it happened in such a funny way. I was driving back from a gig and I was living in Boston. It was late summer [early] fall of ’73 and I had Jim Brewer who I’d brought up from Chicago sleeping in my bed and I was sleeping on the floor next to him. George Thorogood had just moved off my couch and gotten his own apartment.

We were driving back from a gig at Junior College in Franklin Massachusetts. I was booking these acoustic blues festivals as I called them; you got one guy, it’s a show, two guys, it’s a festival. We’re driving back and Jim Brewer is talking about women in the audience. Now, I thought Jim was blind until I went down and picked him up at Penn Station in New York [City]. I’d seen Jim open all these shows for Muddy and Wolf and I booked Jim once… He was always led to the stage, handed his guitar, and when his set was over someone would lead him from the stage, take his guitar. I assumed he was blind and the posters said, “Blind Jim Brewer.’

Then I go to pick him up in New York; he had to change trains to come from Chicago to Boston. I’m thinking I can’t make a blind guy change trains, so I drove down to New York to get him at Penn Station. I had double parked my car and we’re 50 yards from the car and he says, “You still got that red car?” and I said “What?” He pointed and said, “The red car with the white top. You drove me around Chicago in that.” I said “Jim, I thought you were blind. We booked you all these gigs as Blind Jim Brewer.” He says, “Well we say that but I got cataracts, but cataracts ain’t nothing but the language of the blues.”

That’s too funny.

So we’re driving and he says, “That woman in the audience, I’d like to plug into her.” So, I started vamping. I was always writing songs. “The men call me Jim; the women call me Electric Man. When I plug into your socket, I’ll charge you like no-one else can.” He said, “That’s good shit boy, you ought to give that to Muddy Waters.” He knew I was a fan of Muddy’s and I would see him from time to time.

Muddy comes to Boston about four weeks later and I go backstage to see him at Paul’s Mall, the club where these guys played in Boston. He recognized me and he was happy to see me and said, “Ah, a familiar face.” We’re in his dressing room, he’s drinking champagne out of a paper cup. I said, “You know Jim Brewer?” and he said, “Kind of.” [I said] “He wants you to hear this song I wrote.” I could not go backstage and present a song I wrote to the Allman Brothers, or Cream, or Chuck Berry.

But here’s the guy who they all learned from and he puts his hands on his knees and says, “Let’s hear what you got.” So, I just let it rip. “The men call me Muddy, the women call me Electric Man. When I plug into your socket, I’ll charge you like no one else can.” He said, “Keep going – keep going.” I went through the whole song and he said, “That’s good shit boy, you write that down.”

So, that’s a circuitous way to get to what you asked me, but the point is, it happened so fast, so effortlessly. It was all like a dream.

After every show in Boston we would walk down the street one o’clock in the morning from Paul’s Mall to a club called Ken’s Pub and we’d go [sit] in the back at a dark table with a little candle in a white bowl with a little white plastic net around it, and he says, “Get the napkins boy.” I get a stack of cocktail napkins and I come back to the table and we sit there by candlelight, one o’clock in the morning and we and bounce song ideas off of each other and I scribble them down.

He’d say why didn’t I go to New Haven and out to Buffalo… “Ride with the band.” So, I’d ride with the band. I’d work the radio sometimes… I’d be in one vehicle and Bob Margolin would be in the other so there’d be a white guy in each vehicle.

I wanted to ask you about that… There’s a story that you’ve told of how Willie Smith told you that you should listen to country, and why that was so important.

I’m riding shotgun up front so the police would see me if it came to that. I’m working the radio and we’d listen to whatever came in steady but mostly it was rhythm and blues. When those faded into static, this is AM radio remember, I had to work the dial until I found something that they could listen to. I come by a country station and Willie says, “Leave that.”

I’m thinking really? Why are these black guys from Mississippi listening to this redneck music? It was like music for the lynching after party.

I asked him “What’s with this?”

Remember: This is like late ‘60s early ‘70s but still, one of the reasons the music affected me so much was seeing it at these little places in Chicago like Alice’s and the Quiet Knight. We’re still in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement and I’m looking at these black guys when I would go see them and I’m thinking these are these black guys who made it out of Mississippi alive and they brought me their music. I was very conscious of the fact of what had been going on. We’re listening to country music and I’m thinking this is redneck music.

And Willie said “Listen to the words. Same stories.” It’s true! “My woman left me,” “I got no money,” “I’m a badass guy,” …

“I lost my truck.” “I lost my wife.” “I lost my dog.”

Yeah, exactly! So, the stories are the same. There was a definite connection with these blues guys what they were hearing in the lyrics of the country music.

Nice!

And I got into country music. I thought “If it’s OK with these guys, then it’s OK with me.” It was always stuff that had a lyrical hook like the blues did. If you listen to my lyrics you’ll notice that I didn’t stray too far from that: Bobby Bare, “I Never Went to Bed with an Ugly Woman, But I Sure Woke Up with a Few.” That’s actually a Shel Silverstein lyric. So, I started writing that stuff.

There are two sides to everyone: There’s the public side of an artist and there’s what they’re really like. The public, they get the myth – they get the legend. For the most part, they have not had the access to the folks that they look up to the way that you and I have. People like Freddie King, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, and Howlin’ Wolf. For instance; everyone loved Hubert Sumlin. On the other side of that coin, you have all the talk about how fearsome and tough Howlin’ Wolf was. Since you knew a lot of these folks, was there a real difference between the public perception and what they actually were?

I knew Wolf where he would recognize me; I doubt he ever knew my name. I was around him in a more of a superficial way. I had more of a relationship with Eddy Shaw, Hubert Sumlin – I knew him. I never really got a sense that Wolf — I never saw a side to Wolf that I wouldn’t have seen on stage or hanging out or by the side of the stage. He wasn’t as chatty in my recollection as Muddy could have been.

I didn’t see a hidden side of Wolf, as much as I saw the private side of like Muddy.

Muddy… I remember him being pretty gracious in most circumstances. I will say that I loved being his pal. I loved writing for him. I loved watching him just interact backstage with people like Johnny Winter and the Stones. B.B. King.

Right.

I would not have wanted to be married to Muddy Waters. He liked the women. He would you know, be very welcoming of any pretty girl that came backstage. Remember also that I knew Muddy pretty much for the most part when he got into his late 50’s. That’s when I met him… [in] ’69 he would have been 56. So, he was slowing down a little bit as far as romantically but not that much. He had young girlfriends, and he had a young wife and I don’t think he ever took his eyes off the girls.

Keep in mind it’s show business, OK? When he gets up onstage he may hear bad notes; he may hear the guys in the band doing stuff that he wasn’t thrilled about. He’s not gonna open up onstage about it. He might give someone a look, or he might give someone a signal, but anything along those lines, any kind of business that he had to take care of or fix something that wasn’t working right, he did it backstage. He did it briefly, he did it with a few words. I did not ever see Muddy in a brooding kind of state.

Right.

He was open with me. We’d talk about how he related to this woman or that woman, or what that woman had been like for him, but I would say he was always gracious with me in my presence when I when I could see him interacting with other people. He was always a gentleman, he was always a simple man. I think he had, by this time a feel for how to deal with people in a gracious and politically correct manageable way.

A guy like Hound Dog Taylor, you saw a guy like that I think, a lot more pissed off in public than his onstage persona would be. He was kind of an ornery guy.

Hmmm.

And you could see it in how he treated his bandmates and you could see it in how he treated people that he really didn’t have much use for. I didn’t know Hound Dog that well, but like I said, I was backstage with him a few times, I was at non-musical situations with him; he was not I think… that there was more of a disparity as to how he acted onstage and how he acted people backstage. I didn’t see it that much with Muddy.

And John Lee Hooker?

I didn’t really know John Lee. I knew him to say “Hi, how ya doin’?” The one personal experience I had with him [was] when we used him on a Levis commercial. He was totally gracious. He was there to take care of business, get the commercial; he was getting a lot of money to play for an hour or less.

Absolutely.

I will tell you though it was a very unexpected and weird situation when I did John Lee into the studio. Levis had a reputation for doing really cool commercials and they had to pay to maintain that. I wanted to work with John Lee Hooker so I said, “Let’s do this now.” It was a natural for blue jeans. “I can’t eat. I can’t sleep. I’m waist deep in the blues. All I can do is boogie.”

Right on.

They said great, get John Lee. So, I got him. We get into the studio in LA and I wanted him to do this riff that I think was off Hooker and Heat. He had his guitar with him. It was a Gibson hollow-body and I played this piece that I wanted him to try to replicate and he says “Well, I don’t do that no more.”

I said “Can you do it for the commercial? I kinda told the Levis people this was what it was gonna be like.” He says, “I don’t do that.”

Oh man.

One of two things were at play here. He couldn’t remember how to do it, but more likely, and somebody mentioned it to me afterwards and it made perfect sense, that the riff I wanted him to replicate very well may have been done on Hooker and Heat by Harvey Mandell or Alan Wilson, to begin with. Hooker never played that riff.

Could be. You never know.

He was cool about it. He just said, “Well, I can’t do that.”

That’s funny.

Always a gentleman, always cool about it. “I don’t do that.” So, mercifully, the engineer said, “I got a guy” and said I “Great.” Half an hour later, into the studio walked Hollywood Fats.

Oh wow. How cool is that?

So he got it first time.

Yeah, Fats was amazing!

These guys were full of surprises and it was a much kind of looser art form where you could take liberties with this stuff. It was always a journey of discovery to be with these guys and see where everything they brought to us all — where it had come from. How it got there, and how they viewed it.

To a certain extent, Muddy would give these guys onstage some latitude and it had to be totally in the pocket, or they’d hear about it.

As opposed to Albert King, who was very exacting. Stories abound about how if you were in his band you’d better be towing the line. You better know your part, you better do it right and don’t even think you were gonna be slacking.

I know what you’re saying and I remember hearing that about Albert and I would say that it’s not like you would get a sloppier performance with the guys in Muddy’s band, but I think that he also gave the guys latitude, but you had to deliver on what he expected. And, he was not shy about making it known that it wasn’t quite there.

You once said that the blues “has real roots and it tells the story of America and it instills a unique geographic pride, if not chauvinism, in people who got to grow up where it started. For me, it’s Chicago. For someone else, it might be St. Louis or Memphis or Kansas City or Mississippi. Also, there are so many emotional dimensions of the music that are universally accessible. It’s easy music to connect with.”

My entire orientation to the blues came out of the British invasion. The first time I went to hear a blues singer, my buddy Abe Trieger called me up and I was home from college — it was 1969, and told me “There’s a band playing by Wrigley Field in a bar and they do the Stone’s ‘Little Red Rooster.’ Wanna go see them?” I asked him the name of the band and he said “The Howlin’ Wolf Band.” My response was “Well we like the Animals, maybe we’ll like a band called the Howlin’ Wolf Band.”

So, we’ll go see the Wolf, not only because he does “Killing Floor,” which we thought was a Jimi Hendrix song… He did “Back Door Man,” which we thought was a Doors song. He did “Spoonful,” which we thought was a Cream song. As I discovered when I went home, he had created or performed the music that Willie Dixon had created for all these young rock bands. That was the hook! That was the allure of all the blues bands, and it was all in Chicago.

We started researching this and looking at who actually wrote these songs, and we hit the motherlode. Because the train from Mississippi came up to Chicago, that’s where they were. Of course, it’s simple stories and universally relatable. What hit me was the language that was used. It wasn’t “Turn around so I can see your butt.” It was “Stoop down baby and let your daddy see, there’s something down there that’s worrying the hell out of me.”

That’s what I loved. Eddie Shaw sang that and it sunk in. Or “My baby rode off with the bus driver and it don’t seem right. He was giving her rides in the daytime, and now she gives him rides at night.” It’s sex man! It’s one way to say it.

Look at the stuff that was going on in the ’30s like “My Pencil Won’t Write No More,” the rest of the Bo Carter stuff; a lot of that was sex as well.

“Churn until the butter comes.”

Sure. The whole “Squeeze my lemon” thing. That’s been going on for generations now.

I talk about this every chance I get. I grew up learning to read from Dr. Seuss and MAD Magazine… and it was all made better by whimsy. THAT’S what I heard in the blues language. I heard the power of whimsy. When you listened to the Temptations, it didn’t sound like the Beach Boys. It didn’t sound like a lot of the white folks that we were listening to. The music was different. The lyrics had snap, whimsy, and the wink of an eye. And THAT was SO pervasive in the blues.

What about Muddy and the Stones?

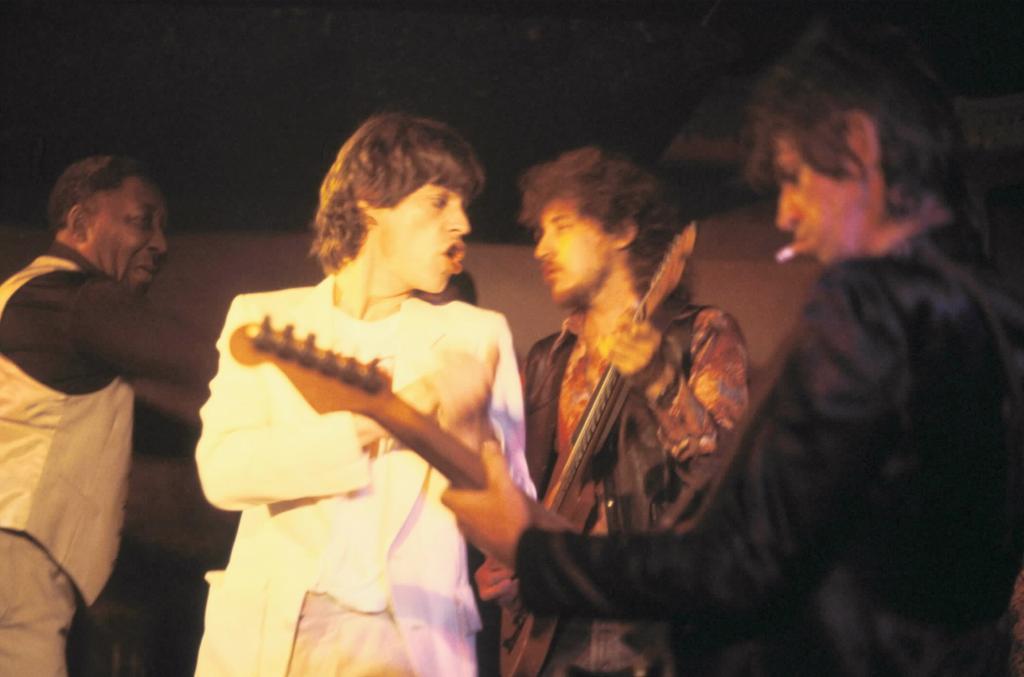

The pictures I have of Muddy and the Stones were shot in 1978, ’79 at the Quiet Knight, a little bar by Wrigley Field where I first saw Howlin’ Wolf. I was backstage with Muddy and he said to me, “Don’t say nothing boy but the Stones are supposed to show up.”

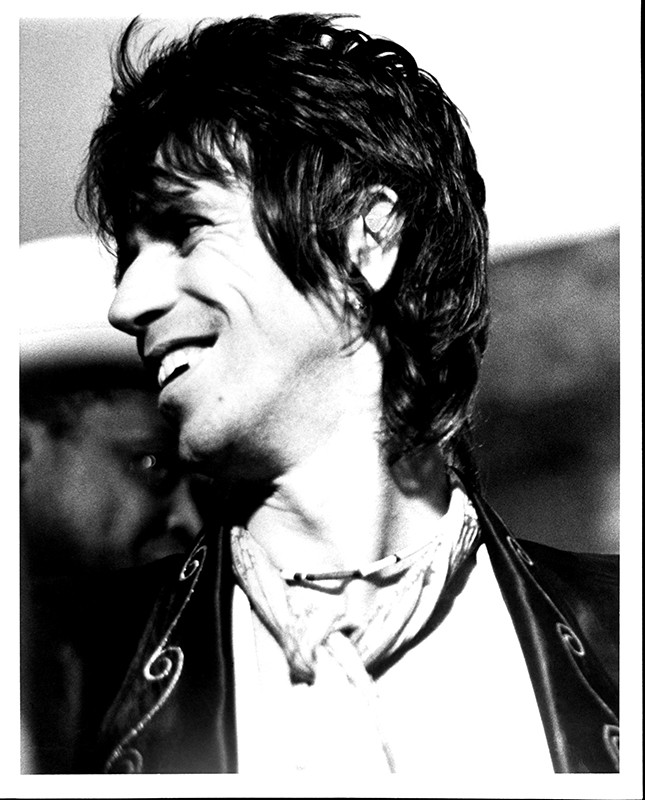

Between sets, Keith Richards appears in the doorway of the dressing room and he’s standing there with a cigarette hanging from his lip by one grain of tobacco. He looks around the room and says nothing. He sees Muddy sitting and his eyes lock on Muddy across the room. He kind of bounces toward Muddy. He had a very funny and unique way of walking — and he bounced over to Muddy. He gets to Muddy and he doesn’t say anything. He gets down on his knee and takes Muddy’s hand off his knee and he holds Muddy’s hand in both of his and kisses the back of Muddy Waters’ hand.

To me, that was a memory. Then there’s Ronnie Wood, Charlie Watts, and Mick Jagger. Jerry Hall came in a little while later. They hung out backstage for 20 minutes or so and then Muddy started his set. Muddy had a lot of kids as you know, from different situations, and he had a lot of his young kids there with him that night. They were sitting onstage and went to sleep between sets. My girlfriend Susan and I got there close to the stage. Muddy does a song or two and then he has Willie Dixon come up and it was the first time that Willie Dixon had performed after having his leg amputated.

That must have been a moment.

That was dramatic. Muddy says, “Where my friends? Mick? Charlie? Keith? Ronnie?” And the Stones come out from the back and the Stones come out and they play with Muddy for 35 minutes. It was incredible. It was a tremendous memory ‘cause, you know… I’ve got goosebumps now telling you the story.

The first blues singer I’d ever gone to see was Howlin’ Wolf nine years earlier in THAT room because my buddy had said “Let’s go see this band that does the Stones’ “Little Red Rooster.

Terry Abrahamson

Terry Abrahamson on Facebook

*Featured Image Photo is ©Terry Abrahamson