Shake Your Hips: The Excello Records Story is one of the debut titles from BMG Book’s “RPM Series.” Beginning November 20th, the series will feature stories of influential record labels. Each is sized at 7″x7″to mimic the dimensions of a 45 RPM record, and each features a photo insert that helps brings the story to life with rare and unseen photographs.

Through extensive research and interviews, Shake Your Hips: The Excello Records Story chronicles the tale of one of the most unusual labels to emerge from the 1950s. Shedding new light on Nashville’s rich history as much more than a country-music town, the book takes readers deep behind the scenes of the rise and fall of an inimitable label whose contributions to blues and R&B continue to reverberate today.

The following is an excerpt from Shake Your Hips: The Excello Records Story:

In the late 1940s, Nashville record store owner Ernie Young forged a partnership with 50,000-watt clear-channel radio station WLAC. The influential station’s dusk-to-dawn broadcasts of rhythm & blues captivated millions of listeners and crossed racial boundary lines, along with making Ernie’s Record Mart one of the most successful mail-order record retailers in the U.S. In 1951, Young launched the gospel label Nashboro Records and a year later the R&B subsidiary Excello.

Young’s unusual business model — package deals of R&B singles featuring four hits and at least two Excello or Nashboro releases — meant that every record he released was a sell-out, hit or not. Even though hits weren’t his primary focus, Young turned to Nashville’s thriving jump blues scene for talent and Excello scored big with several instrumentals by Nashville’s Kid King’s Combo and with “It’s Love Baby (24 Hours a Day)” by Nashville nightclub stalwarts Louis Brooks and his Hi-Toppers, with Earl Gaines on the lead vocals.

Most of Excello’s success through 1954 in the R&B field centered on the brash and sassy R&B of uptown blues and small jump groups like Kid King’s Combo and Louis Brooks & His Hi-Toppers. Although that style ruled in Nashville’s swankier black nightclubs, the city was also home to several down home bluesmen plying their trade at small, out-of-the-way beer joints. Starting in 1953, several of these artists found their way to Ernie’s Record Mart, and while their records failed to match the sales of the saxophone- and piano-driven jump combos, they certainly earned their keep.

Several of these Music City bluesmen, including one who rose to greater prominence, first recorded for Ernie Young in the summer of 1953 as part of a short-lived ad hoc combo known as the Leap Frogs. The group combined two different blues combos that were frequent visitors to Ernie’s after the launch of Excello. Young teamed the duet of Louis Campbell and Jimmy Johnson (vocals and harmonica, respectively) with Arthur Gunter’s Trio—Arthur Gunter and his younger brother “Little Al” on guitars, and cousin “Junior” Gunter on drums.

The result, “Things Gonna Change,” was a fine example of shuffling country blues with a catchy and scratchy vocal by Campbell, sharp harmonica fills by Johnson, and cookin’ rhythm by the Gunters. The flip side, “Dirty Britches,” was a hot instrumental jam showcasing Gunter’s lead guitar work. Released in October of 1953 with the usual promotional push on WLAC and trade ads in Billboard and Cash Box, the single failed to catch on with audiences.

Although the Leap Frogs had only one collective shot on Excello, the individual members continued haunting Ernie’s shop, so Young mixed and matched the musicians for several subsequent recordings. Two of the former Leap Frogs turned up on Shy Guy Douglas’ second waxing for Excello, “I’m Your Country Man.” Cut a few months after the Leap Frog session and released in December 1953, the single was an answer song to Big Maybelle’s current hit “My Country Man” on Okeh Records. While Douglas’ first Excello single featured a more uptown sound courtesy of Kid King’s Combo, Young apparently wanted a more down home feel to match the song’s rural subject matter. To capture the country shuffle sound, he tapped Skippy Brooks on piano, Jimmy Johnson on harmonica, and Arthur Gunter on guitar.

June 1954 brought Louis Campbell back into the spotlight for his first (and only) Excello recording under his own name. “Gotta Have You Baby” featured Jimmy Johnson on harmonica, Skippy Brooks on piano, and an unknown guitarist with a more sophisticated down home sound, similar in style to B.B. King.

Despite his mastery of the form, Gunter did not begin his musical career as a bluesman. A native of Nashville, Arthur Neal Gunter was born on May 23, 1926. The third son of the Reverend William Gunter, Arthur was drawn to gospel music by performing with his brothers, Larry, Jimmy, and Little Al, along with their cousin Junior Gunter as the Gunter Brothers Quartet in Tennessee and Georgia. After learning the basics of the guitar from his older brother Larry, Arthur became entranced by the blues. Little Al and Junior followed him down the path to the “devil’s music.” In addition to performing with his brothers and cousin as the Arthur Gunter Trio, he also sat in with various bands around Nashville, including Kid King’s Combo.

![Excello - Baby Lets Play House Label[1]](https://www.americanbluesscene.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Excello-Baby-Lets-Play-House-Label1.jpg)

Ernie Young finally struck country blues pay dirt in December 1954 with the release of Arthur Gunter’s first “solo” record, “Baby Let’s Play House.” A mix of older lyrics that hewed to the well-worn blues recipe of blending female adoration with misogyny and threats of violence, Gunter brought a laconic, deadpan vocal delivery to the material.

Loose, sloppy, and teetering on the edge of chaos, most labels would never have considered releasing the recording. It perfectly embodied the “feel over technical quality” aesthetic that Sun Records head Sam Phillips would later dub “perfect imperfection.” In Phillips’ case, it was a deliberate artistic choice. For Ernie Young, it was simply a matter of “that’s good enough.” Whatever the motivation, this willingness to release music that valued visceral appeal over conventional polish produced vibrant and transformative records.

“Baby Let’s Play House” won an immediate following on WLAC, and as the mail orders began to pour in, other stations gave the record a spin. It entered the Billboard R&B chart in the last week of January 1955, hanging on for three weeks and rising to the number twelve position. The moderate success of the record afforded Gunter’s trio the opportunity to tour regionally in the late winter of 1955, appearing at juke joints in Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and North Carolina.

Young was eager to follow up on the success of “Baby Let’s Play House,” and released Gunter’s second single, “She’s Mine All Mine,” in February of 1955. With a similar driving rhythm and more praise and threat–laden lyrics, the single was a hot platter on the turntable, but unfortunately failed to catch fire on the charts. Meanwhile, outside forces would soon guarantee Arthur Gunter’s musical immortality and make “Baby Let’s Play House” one of Excellorec Music Publishing’s biggest money earners.

Young was eager to follow up on the success of “Baby Let’s Play House,” and released Gunter’s second single, “She’s Mine All Mine,” in February of 1955. With a similar driving rhythm and more praise and threat–laden lyrics, the single was a hot platter on the turntable, but unfortunately failed to catch fire on the charts. Meanwhile, outside forces would soon guarantee Arthur Gunter’s musical immortality and make “Baby Let’s Play House” one of Excellorec Music Publishing’s biggest money earners.

On February 3, 1955, Elvis Presley recorded “Baby Let’s Play House” for Sun Records in Memphis. As with previous singles, Presley supercharged a country blues tune by adding hillbilly hepcat twang. He also utilized a trick from his first record, when he transformed the bluegrass swing of Bill Monroe’s “Blue Moon of Kentucky” into a boppin’ masterpiece. As with that previous success, he moved a portion of the chorus to the intro and ran it through the rockabilly hiccuppa-sizer. Finally, he added a bit of prophetic autobiography by changing Gunter’s “You may get religion …” line to “You may have a pink Cadillac.” The following month, Elvis would purchase the first of several pink Cadillacs.

Released on April 10, the single sped through the Southern radio markets like said Cadillac, breaking into various regional charts by the first weeks of June and flashing onto the Billboard national country chart on July 15. The single enjoyed a fifteen-week run on the chart, rising to number five, and becoming Presley’s first national hit.

The windfall of publishing royalties for Excellorec and Gunter continued into 1956, when RCA reissued all of Presley’s Sun singles in late 1955. The success of “Heartbreak Hotel” pushed the sales of “Baby Let’s Play House” into the millions, and Gunter later recalled that his first royalty check totaled $6,500.

Arthur Gunter continued recording for Excello through 1961, eventually racking up a total of twelve singles for the label, as well as appearing on two excellent singles credited to his brother and fellow guitarist, “Little Al” Gunter, that were released in 1956 and 1957. The younger Gunter might have recorded more fine blues for Excello had he not been murdered in a bar fight shortly after the release of his second single.

Although Arthur Gunter never duplicated the success of “Baby Let’s Play House,” the singles he cut were all strong examples of Nashville’s homegrown take on country blues, and they were consistent sellers for the label.

After leaving Excello, Gunter moved to Pontiac, Michigan. In 1970, he was rediscovered by blues fan Fred Reif, who booked him for blues festivals and contacted Excello with the singer’s whereabouts. The label signed Gunter to a new contract, but his drinking and unreliability preempted plans for a comeback record. After winning $50,000 from the Michigan State Lottery in 1973, Gunter quit performing.

While Gunter’s initial run of Excello singles performed well at the cash register, that was not always the case for the other prominent down home bluesman who rattled the rafters of Excello’s third floor studio. Between 1955 and 1957, Jerry McCain cut six singles for Young, creating some of the most primitive, idiosyncratic, and oddest recordings released on the label. McCain’s cracked mixture of down home country blues and rock ’n’ roll only sold moderately well at the time but secured him a place as a cult hero to loyal blues fans and record collectors.

A native of Gadsden, Alabama, Jerry McCain was born into a musical family on June 19, 1930. By the early 1950s, he was performing locally with his own combo as a singer, harmonica player, and songwriter. In 1953, he cut his first record for the Jackson, Mississippi–based Trumpet Records, and a second single followed in 1954. Both were fine examples of Little Walter–style harmonica-driven blues, with little hint of the franticness to come.

A native of Gadsden, Alabama, Jerry McCain was born into a musical family on June 19, 1930. By the early 1950s, he was performing locally with his own combo as a singer, harmonica player, and songwriter. In 1953, he cut his first record for the Jackson, Mississippi–based Trumpet Records, and a second single followed in 1954. Both were fine examples of Little Walter–style harmonica-driven blues, with little hint of the franticness to come.

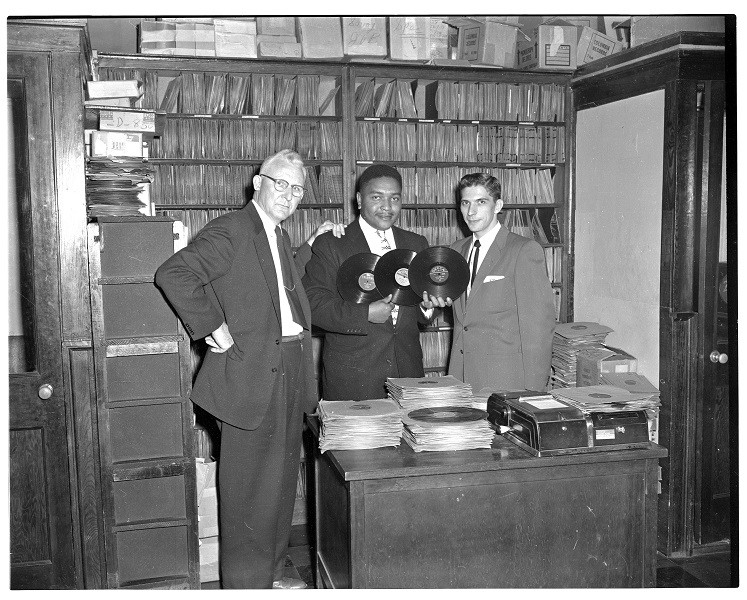

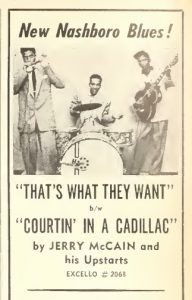

Following the call of WLAC and Ernie’s Record Mart, McCain and his group headed north to Nashville in 1955 for an audition with Ernie Young. McCain’s first Excello release hit the racks in November 1955. “That’s What They Want” was a solid Muddy Waters “Mannish Boy”–style strutter that Young pushed in Cash Box ads with a small photo of McCain and his combo. The real action, however, was on the flip side. “Courtin’ in a Cadillac” was a wild, out-of-control rocker that sounded like it had been captured in mid-escape.

McCain’s next two Excello releases appeared in rapid succession in May and June of 1956. Both followed the same formula, pairing a slow blues strut with a frantic B side. McCain’s fourth Excello release, in February of 1957, really tore the doors off. Although “My Next Door Neighbor” lacked the big New Orleans sax-driven sound of Little Richard’s rock ’n’ roll hits, it matched them toe-to-toe in manic energy and nutso lyrics.

The weirdness was amplified on the flip side of the single. “Trying to Please” featured McCain experimenting with a number of ballad styles, only to be met by a falsetto screech of “I don’t wanna hear that! I don’t wanna hear that!” He finally satisfies his mystery critic with an out-of-control rock ’n’ roll rave-up.

McCain returned to the blues ballad/cracked rocker template for his last two Excello singles. After Young dropped him from the label in late 1957, McCain recorded for a variety of labels, including Okeh, Jewel, Rex, and Ric, and continued as a popular local performer in Alabama. During the 1970s, his Excello recordings were rediscovered and he became a fixture on the blues festival circuit, cutting several albums of new material.

![Excello - Jerry McCain Label[1]](https://www.americanbluesscene.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Excello-Jerry-McCain-Label1-1024x1024.jpg)

Although Arthur Gunter and Jerry McCain failed to deliver consistent blues hits for Ernie Young, a uniquely new variation of the down home sound soon became the label’s trademark. Surprisingly, the blues that established Excello’s fame around the world did not come from the hills of Tennessee, but rather from the swamps of Louisiana.

Excello Records Gear from Bluescentric

*Feature image courtesy of BMG Books via Conqueroo Music Publicity

![Shake Your Hips: The Excello Records Story Excello - Feature Jerry McCain Label[1]](https://www.americanbluesscene.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Excello-Feature-Jerry-McCain-Label1.jpg)