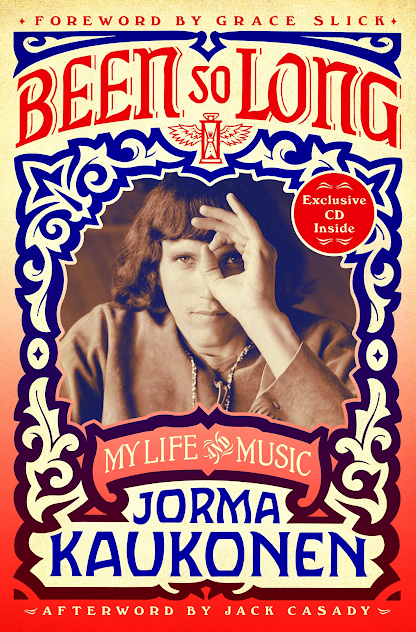

Been So Long: My Life and Music, a memoir by Jorma Kaukonen of Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna, hit the shelves in late August of this year. It doesn’t read like a typical sex, drugs, and rock and roll autobiography. Some parts are almost stranger than fiction: recounts of contracting malaria, live Jonestown radio communication bleeding onto recording tapes from an adjoining Peoples Temple… For any soul who truly appreciates the worldly literary works of Patti Smith, Jorma also has a faculty for sending the reader on a cerebral and countercultural journey.

Was Woodstock really just another gig in a time of unrest and upheaval, of love and peace? Did Altamont mark the end of an era? Been So Long encourages you to retrospectively examine certain landmark events – and also some of life’s hardest choices – not through the bias of hindsight, but more so through the lens of existentialism. All the while, it tells the story of a fascinating life and half-century career in music. As Grace Slick says in her foreword, it is “a modern parable.”

Jorma and wife Vanessa are the proprietors of Fur Peace Ranch, a sanctuary in Ohio’s Appalachian foothills whereby guitarists attend workshops taught by some of the most distinguished interpreters of roots music. Fur Peace isn’t just a music school; the ranch boasts a concert hall, live NPR podcast, an art gallery, and a farm-to-table restaurant called Pho Peace. Musicians who have taught and performed at the ranch include Bob Margolin, Dave Alvin, Chris Hillman, Jack Casady, Jorma himself, and many more.

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee shared his time and wisdom with me in a recent interview, as well as satiated my music nerdom with some amusing facts.

Lauren for American Blues Scene: So, I just finished your book. And I wanted to talk to you a little about that and a few other things.

Jorma:

Of course. Sure.

You mentioned your fondness for Shakespeare studies. Kind of a weird question, but did the iambic pentameter ever serve as sort of a guide to writing your own lyrics?

No. I don’t think that it did, because that would have probably required an intellectual leap of faith I would have been incapable of back then. But I was certainly comfortable with the structure that was afforded in the context of The Bard itself.

Right. Ok. In one journal entry, you said that Kurt Vonnegut never became irrelevant. Rather, time and audience moved on and language changed. That’s a statement that resonated with me. I felt like maybe it was something you could apply to the zeitgeist of today. Do you?

Oh, absolutely. And you know… Yeah. Well said. I mean, you know, the thing is…

Thank you.

Is that I have… Yes, you’re welcome. It’s been a while since I’ve revisited Kurt, but I think I might be about to. At some point. I’m on the road right now — I should have grabbed a book and brought it with me — but it’s just a way of looking at things. People of my generation, and younger generations too, that got into Kurt Vonnegut… You know, I think he opened up windows for us that — they may need to be reopened. I may need to revisit some of these things.

That’s why I re-read books, sometimes like five times. Because certain ideas and theories don’t ever become irrelevant.

No, no. I agree. And you know, I like to re-read books also. It’s been a while since I’ve re-read Kurt. Now recently, we were out with Susan and Derek on the Tedeschi Trucks tour. And when we were in St. Louis, I remember I had a day off — I’m walking around and there’s a building that had a huge five-story portrait of Kurt Vonnegut on the side. And I thought, ‘You know, it may be getting to be time for me to revisit his work again.’

Yeah!

Your father’s line of work took you and your family to foreign places, which can scare or excite — or both — a young kid.

Yes.

You recall a lot of fun memories. Did living and attending school in places like Pakistan and the Philippines create lifelong friendships with anyone?

Actually, it did. Thanks to the internet. I reconnected with a lot of people that probably would have disappeared from my world had it not been for the fact that we’re all reconnecting with people all the time, which is really neat.

Yeah, one good thing about social media.

Yeah, it’s awesome. But one of the other things that occurred to me in the course of doing interviews about the book, that I don’t really think I addressed in my book when I was writing it, was that living abroad in places like the Philippines and Pakistan gave me an awareness of what it was like to be a minority in a context that had I never left the States, it would have never occurred to me. In a good way.

Yeah! Interesting way to think about it.

You mentioned that Altamont was an event where there were no real barriers between the art on stage and the art of the audience. I’m paraphrasing here.

Oh, my gosh.

Some might say that it marked the end of an era. Do you think maybe it was the violent events surrounding it that cast a pall on the “peace and love” message of the ‘60s? Or, I mean, what do you think?

I’m not sure that the event itself created the end of an era. It might have just been sort of an odd, kind of negative synchronicity. Yeah, because time marches on, you know? In 1969 – I mean, we realize today that three or four years is not really a lot of time. But culturally speaking, it can be eons. So, things might have been moving on, and probably were moving on. But I think that what Altamont did — it gave us a point of relevance to say, ‘Ok. That’s when it ended.’ I certainly wouldn’t blame it.

Right. Well said.

It’s funny how a song is born. Sometimes, you’re experimenting in dropped D or perhaps with more complex approaches. Regardless, in your case, it’s the words that follow. My question is, how do they follow?

As a rule, I think that my songwriting normally tends to emanate from some sort of melodic idea, which has happened by messing around on the guitar. In order for it to really work, at least one or two lines has to come along with that. I mean, when I’m messing around with stuff – you know, maybe I’ve learned a new set of chord changes or just something new, you know? Something that makes me mess with the guitar again, not in a rehearsing kind of way but an experimental kind of way. And if something dances across my mind that fits into that space, that musical line of force…then at that moment if I’m on my game, and it doesn’t happen all the time, I’ll jump on that like a dog on a bone. And I’ll start to see where it goes. And then, if I’m getting a lyrical idea, then I’ll expand whatever the musical part is.

Ok. Yeah, and you probably write it down right away, right?

Oh, absolutely. If you don’t write it down, you’ll forget it as if it never was.

Right. You tell yourself you’re going to remember, but…

You never do.

You never do. Not in the same way anyway, I’ve found.

I’m always talking to students when we’re talking about songwriting and stuff. You get this idea. And whether it’s in your head, whether you can sing it, whether it’s on the guitar – and you’re doing something else, whatever it is; walking the dog, putting a plate in the dishwasher, whatever – if you don’t cease what you’re doing and either get a recorder out or somehow document that moment, no matter how you think you’re going to recreate it, it’ll be different. And it will never be that again.

I couldn’t agree more.

One other thing I found interesting: What’s the story with the breaking glass on “Uncle Sam’s Blues”? Why did audience members always literally cue the breaking glass?

Well, I’m not saying they were drunk, but…

But they weren’t not drunk.

I don’t think it was intentional, but the upshot of that was that for years afterwards, every time we played that song, somebody had to break a glass at that point.

Right? It’s so weird.

Yikes.

How does it feel to finally put the words to the story? Your story; your words.

Actually, I really wound up enjoying not only the process but the finished product. My friend, Chris Smither, great singer/songwriter, occasionally when he’s asked about this says, ‘I hate writing songs, but I like having written songs.’ And I kind of understand that on some level. But I gotta say that, once I got into the process of actually writing the book, I really enjoyed the process. And the process itself, not just having done it when I was done. And one of the other things I really enjoyed too is that in the course of that process is that I wound up relieving the subconscious by talking about myself in a lot of ways. I jokingly tell one of my kids, ‘You know, I could have spent thousands of dollars on therapy getting to that point.’

Exactly. That’s why I like memoirs. It’s therapy for me, the reader, too. In particular, I really liked yours. I was greatly inspired by your prose.

Oh, thanks.

With that being said, what advice might you give someone who wants to write a memoir?

I guess, first of all, don’t start with a preconception about how it’s going to go. For me anyway. Look, obviously, I had a timeline of my life to follow up to a point. But I think let the thoughts chase themselves. If you’re lucky enough to have taken notes about stuff over your life, you have things to look at, if you’ve journaled things that jog your mind, or people that knew you to jog your mind. Of course, it might not be a good jog, because everyone’s got their own take of stuff. I think that just starting the process and seeing what makes the next word emerge is kind of what I did.

And writing regularly keeps you sharp.

Yeah, it does. And of course the more you do anything, the better at it you get. But one of the things I noticed also, because I enjoy journaling. My little blog, sometimes it’s more interesting than others; sometimes it’s like a setlist. You know, I went to New York City and I ate at Zabar’s, or whatever…but sometimes it’s more interesting. However, to actually sit down and to write a book was a different process for me. And I needed to get away from needing that moment of inspiration to come up with something. I had heard somebody, and I can’t remember who it was. I think it was on an NPR show. It was some Hollywood producer that did all kinds of stuff. He wrote, directed, all sorts of things. And she asked him when he was writing if he waited for that moment of inspiration. His thing was, “If I did, I’d never get anything done. I let the process be my inspiration.” And that really resonated with me, and I still hold on to that.

Yeah. Just like in your book when you talked about visiting family. If you waited until you actually had time, that day would never come. It sort of reminds me of that.

And I also gotta say, speaking of that, when I wrote this stuff — you know, you lose people. Obviously, there are emotional moments and stuff like that. When I wrote that, I was able to really, not look at it dispassionately, because these are passionate moments, but I was able to get through it. But when I did the reading for the audio books, that was tough to read out loud. That was a whole different ballgame.

Well, yeah! And I feel like you’re a living testament to someone who actually feels the art that they create. Because I could feel every emotion while I was reading your book. And same with guitar playing and songwriting…you have to feel it, you know? To make the art.

Right. Well, thanks. I think to be able to somehow make it possible for your readers to actually feel what you feel in some way, I mean, that’s definitely a goal.

Oh, can you explain how the idea for the Jorma M-30 came about?

Oh, the guitar?

Lauren: Yeah.

That’s funny. I was just thinking about that today when I was stringing my guitar. That is directly attributed to David Bromberg. You know David, we all know David. He’s a great guitar player, great musician, and a really good guy. Anyway, he had done many years ago with Matt Umanov, this guy who used to own a guitar shop in New York, had gotten together with David. And Martin had made an f-hole guitar to try to go head to head with Gibson’s L series of guitars. It was a flat back, arch-top guitar. It was something that just never worked for them. Matt and David took one – I forget what model – took one of these Martin f-hole guitars, took the top off and put a flat top on it, and created a 4/0” size guitar. So, sort of a large body of guitar. In any case, he created this thing and they built a guitar for David. And over the years, Martin did a signature guitar for David based on that. And I played that guitar and bought one. That was absolutely the inspiration of where I wanted to go with the M-30 because I wanted a large body guitar, but not so large that it’s tough to get my arm over it. Because my rotator cuff, I don’t like having my arm stuck up that much. The Gibson guitars I played were sort of fat. Great guitars, but my arm wasn’t comfortable. And I wanted the long scale and all this kind of stuff. So, spurred on by the legwork that David had already done, I created that. I co-opted a lot of his ideas. I made some aesthetic changes of my own.

That’s good that you designed one that’s more comfortable. So, you still play that one, right?

Absolutely. In fact, I don’t need three of them, but I have three of them.

Right!

Did you find yourself in a whirlwind of emotion or stress at the time Hot Tuna was gaining ground as Jefferson Airplane was sort of coming to an end for you?

I don’t think so. I think that you know, it’s really interesting. If I’d been more tuned in to the possibilities of the concept of future either being positive or negative, that might have been the case. But I think I just took it as the natural course of things. And it just seemed to transit if not smoothly, certainly naturally.

Was Paul Kantner a token of inspiration to materialize Hot Tuna?

In a way. Jack and I had been doing some acoustic stuff. And at some point – my recollection is the Fillmore East. I wouldn’t bet the farm on it, but I think it was. Paul was telling me and Jack, ‘Why don’t you guys play an acoustic song?’ This was way before Hot Tuna. I had my acoustic guitar and I went up to the mic and played a song. And Jack played electric bass. And the folks liked it.

I think it became apparent that we could do that. So, yes, definitely thanks to Paul for that. And I also believe, if my recollection can be trusted, that Paul also came up with the name Hot Tuna. My recollection is we were driving in St. Mark’s Place in the East Village. We played this Blind Boy Fuller song called ‘Keep on Truckin’, Mama.’ For some reason, I don’t know if we were playing a cassette or singing it. I don’t know what the deal was, but somehow the song came up. And the line, ‘What’s that smell like fish, baby,’ which was in the original song, came up. My recollection is Paul said, ‘Hot Tuna.’ And Jack and I went, ‘Well, that’s a great name for a band!’ In our defense, it was the late ‘60s.

Yeah, well, you know?

I do know.

What can you do?

Nothing.

Lauren: Oh, I wanted to talk about Fur Peace Ranch a little bit. I saw a picture of you and Dave Alvin. I’m actually a big fan of his work.

Well, you know, Dave is the real deal. And he’s one of those guys that whenever people ask me, ‘Who would you like to play with that you haven’t played with professionally?’ I always forget. Thanks for reminding me. I always forget that one of the guys I’d like to do something with sometime is Dave Alvin. I’m a huge fan of his. I love the earthiness, and at the same time the multidimensional aspect of his writing. I love his voice, I love…

His voice!

Yeah, he’s great. Quite simply, he’s great.

And was Chris Hillman another instructor?

Yeah, Chris Hillman was an instructor, too. He and Herb Pedersen have come together several times. Herb Pedersen is a guy that I met in 1962 when I moved to California. He was playing in a bluegrass band out of Berkeley. And of course I met Chris later. They’re both great guys. Chris Hillman, you know, he’s such an artful singer. Just a really good guy. His music is always so beautiful.

He’s from only one of the greatest bands of all time.

Yeah, and there’s nothing wrong with his Desert Rose band either.

Agreed.

I wanted to ask you — Did Bob Margolin ever teach at your ranch?

Absolutely.

Ok. I interviewed Bob, and I thought I remembered him mentioning something about Fur Peace Ranch. And I wanted to make sure.

If you get a chance to take a workshop and hang with a guy like Bob Margolin, who played with Muddy Waters for 10 years and is such a master of the blues…

No big deal.

I mean, yeah. How awesome is that? Really.

He’s awesome.

He’s the best. He is a good guy. Here’s a question: Have you ever seen him without his sunglasses? I haven’t.

No, actually. That’s funny that you say that, because that makes me think of Jeff Lynne, too.

Sure.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen Jeff Lynne without his sunglasses on.

No.

That’s funny.

I understand you have rotating exhibits at your Psylodelic Gallery?

Sure.

And you have featured Grace Slick’s artwork. What kind of paintings does she do?

Well, Grace’s artwork is really interesting. And one of her featured characters, of course, various incarnations of ‘White Rabbit.’ Big surprise. I’m not an art critic and I’m probably not the right person to ask, but there are some aspects of her work that remind me of primitive stuff like Grandma Moses, you know? It’s just really good stuff. I have one of her paintings that’s a painting of Monterey Pop. And it’s got all the characters, but she left Paul Kantner out. And I remember, I said, ‘Grace, you left Paul out.’ She says, ‘I just forgot. Doesn’t mean anything.’

She’s eccentric, huh? In a good way.

In a good way. Yeah.

I remember reading – you mentioned in the book that she had perfect pitch…

Oh, my God.

And I think Jack said perfect vibrato. And I can really relate to thinking that myself. Because I remember being a teenager and – I was in chorus for like 6 years – and I remember having “White Rabbit” on repeat, trying to get her pitch down at the “feed your head” part, and I could not do it. And I remember getting frustrated.

She’s awesome, you know? It’s unfortunate that she’s chosen not to sing anymore, but she just had that talent. Whatever it was.

Virtuosic.

Absolutely. I couldn’t agree more. She was just really special. And I heard this thing floating around the internet last year how someone got the multi-track of ‘White Rabbit’ and just played her vocals by itself.

That’s all you need, really.

It’s awesome. It’s totally awesome.

My last question for you is, in light of Marty Balin’s passing, what do you think people should know about him that they may not?

Wow. I wrote a little thing on my blog called ‘Now We Are Three.’ It pretty much sums up how I felt about the whole thing. If it hadn’t been for Marty, none of that Airplane stuff would have happened. As the band evolved, you know, Paul and Grace assumed sort of ascendance in some creative ways. But if it had not been for Marty, none of that would have happened. My line that I do remember from that thing I wrote was, ‘Marty always reached for the stars and he took us with him.’ I mean, I just really couldn’t say it better than that, because that’s what he did.

Jorma Kaukonen

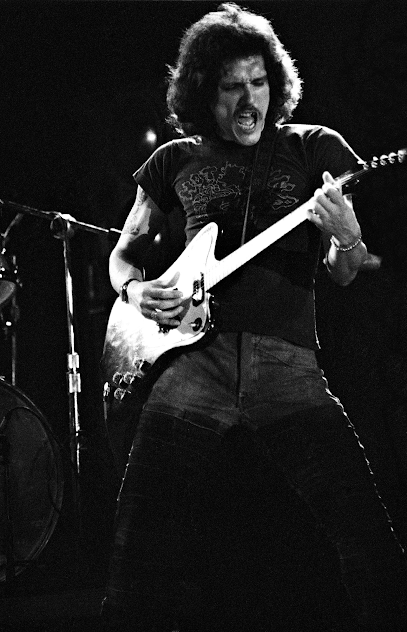

*Feature image Scotty Hall

**All other images courtesy of Cash Edwards Music Services