Robert Mugge is an American documentary film maker. He has focused primarily on films about music and musicians. He’s done several movies on the Blues. Deep Blues, a 1991 film narrated by Arkansas music writer Robert Palmer, features performances by Mississippi masters R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough. Mugge said that a major point of Deep Blues was that pockets of authentic Mississippi blues were alive and well. But by 1999, when he made Hellhounds on My Trail: The Afterlife of Robert Johnson, “I started to sense (Mississippi blues) was beginning to die. A lot of performers were dying, and jukes were closing down.”

That concern prompted him in 2003 to make Last of the Mississippi Jukes. While it’s full of high-powered performances by Alvin Youngblood Hart, Chris Thomas King, Vasti Jackson, Bobby Rush, and Patrice Moncell; it’s ultimately a sad film. Mugge has made documentaries about bluegrass, reggae, and Hawaiian music and has done films centered on Rubén Blades, Sonny Rollins, Robert Johnson, and Gil Scott-Heron. In 1984’s Gospel According to Al Green, Mugge became the first interviewer to get the soul singer to open up about a terrible night in which a spurned girlfriend threw a pot of boiling grits on him.

Brant Buckley:

What’s your favorite Blues Documentary that you have filmed and why?

Robert Mugge:

I’ve made fourteen Blues films not counting other films that have included one or more Blues songs among those from other musical genres. For years I intended to do something on Mississippi Blues. Although I was born in Chicago where my father was getting his Doctorate in Sociology from the University of Chicago, I have southern roots. He was doing his dissertation on Black migration. We moved to Atlanta where he taught at a Black University. I also lived in Washington D.C. and Raleigh, North Carolina. We moved to Silver Spring, Maryland outside of D.C. where I grew up. Washington D.C. aside from the Federal Government is largely a Black city. My mother was from Birmingham, Alabama and my father grew up in Tampa, Florida. Both of them had deep southern roots even though they were heavy into the Civil Rights Movement.

I’ve always had interest in the south. After making the Al Green film, I became more interested in doing a film on southern Blues. I was especially interested in Mississippi Blues. Dave Stewart of the Eurythmics grew up in Northern England. He had a cousin in Memphis and he would receive records, blue jeans, and other southern related things. After he became successful with the Eurythmics, he wanted to give back. He decided he wanted to do a film on Mississippi Blues. He contacted music writer Robert Palmer and Robert said, “If you get Robert Mugge to direct it, I will work with you.” Although I have made many Blues films, “Deep Blues” is still my favorite. People know me for this film over any other. It had a theatrical release and played at Sundance and The Lincoln Center in New York. It’s been all over the world. It captured very important artists who were not around for much longer after the film released. R.L. Burnside, Junior Kimbrough, Big Jack Johnson, Jack Owens, Bud Spires, Lonnie Pitchford, and Jesse Mae Hemphill are all dead. If you think about it almost everyone in that film is now dead with the exception of Dave Stewart. If you don’t capture certain things fast enough, they’re gone. I’m proud the film helped these Blues artists receive national attention and record for Fat Possum Records.

I also love my following films: “Pride and Joy: The Story of Alligator Records,” “Hellhounds on my Trail: The Afterlife of Robert Johnson,” “Last of the Mississippi Jukes,” and “Deep Sea Blues.” I did a couple Zydeco films which are related to Blues. My 2015 film, “Zydeco Crossroads: A Tale of Two Cities,” was funded by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage. In the years since we made ‘Deep Blues, nearly all of my music-related films have contained at least a couple of Blues numbers.

What film projects are you currently working on?

I continue to present a lot of my early films in public screenings. Over the past few years, I’ve also remastered a lot of them, with MVD Visual releasing or rereleasing 22 of the 36 or so films I’ve made. A few weeks ago I was in Montreal overseeing the remaster of my 1991 film “Deep Blues.” Dave Stewart of The Eurythmics originally funded the film and made a few appearances in it. He agreed to remaster the film and wants to relaunch it in the near future. I remastered it in Montreal and he slightly remastered the soundtrack. We are talking to distributors about getting it back out. I was just in Baltimore at a film festival presenting my 35 year old film on Al Green. It’s amazing how some of my films continue to be in demand for screenings around the world. It’s weird that my early films are getting screened most widely.

When you do something for a long period of time there are periods when you are tapped into funders and there are periods when you aren’t. Since relocating to the Midwest to teach, I’ve lost some of my connections with funding sources. I am in another rebuilding faze. Several years ago, I filmed 3 days’ worth of interviews with Steve Bell. He was a correspondent at ABC News and the original anchor for “Good Morning America.” He covered: The Newark riots, the shooting of George Wallace, the attempted shooting of Gerald Ford, Watergate, the 1968 Chicago Convention, and the assassinations of John F Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and Robert Kennedy. Steve Bell came to Ball State to serve as their first Endowed Chair of Telecommunications. I was the fifth person to hold that same position. We hit it off and he kept telling me these incredible stories. I decided I had to document them. My wife and I spent 3-4 months organizing his one hundred best stories and spent 3 longs days filming them. I then took his 22 best stories and made them into a 2 hour film. At the end of this month, I am applying for a $200,000 completion grant.

I’m also writing a book. I just finished my third rewrite for the publisher who is interested. It’s a book about the original Robert Mugge; my great grandfather who came to this country from Germany in 1870 as a 17 year old. It will be called “Saloon Man: A German Immigrant Battles the Limits of Liberty 1870-1915.” He was called the Saloon Magnet of Southern Florida because he owned 20 saloons. He owned a distillery, a wholesale liquor business, and hotels. He was very controversial. He owned a liquor businesses during Prohibition and Temperance. He was in the segregated Deep South and insisted on working with African Americans. He would take out saloon licenses in his name and turn them over to African American managers who then hired African American staff. This greatly aggravated the Jim Crow South especially white southern Americans who were Civil War Confederate Veterans. He was constantly at odds with the police. He would take out newspaper ads attacking the police as being totally corrupt. He was a very colorful and successful character. I am hoping my latest re write will satisfy the publisher so we can get it out.

In your film Gospel According To Al Green, while Al was in the studio you captured a beautiful red background. How did you achieve this and what is the significance of the color?

I made the film after Al Green’s traumatic hot grits incident and others led him to give up performing popular music and become a gospel preacher. A girlfriend asked him to marry her and he wasn’t interested. She threw hot grits on him and badly scalded him giving him third degree burns. She shot and killed herself. This was the last straw that led to him abandoning popular music. He bought a church in Memphis and committed himself to only Gospel music. I came in with the backing of Britain’s Channel 4 television and I made the film “Gospel According to Al Green”. It was heavily centered on what he was doing at the time and his previous career. As a popular artist he inspired romantic thoughts in female fans. He would throw red roses to the crowd during his concerts and it made me think about the color red. I knew we were going to be discussing a lot of the recent torment in his life. Ingmar Bergman’s wonderful film “Cries and Whispers” dealt with torment of the soul. I read in an interview that he used red in the film because he considered red to be the color of the human soul. Since I was dealing with various types of soul and soul music, I thought I’d use this motif.

It happened naturally when we filmed the concert. There was a lot of red around especially red flowers on tables. When we filmed in his recording studio in Memphis, he finally gave me an interview. After we filmed a staged rehearsal I convinced him to do the song “Let’s Stay Together” and he turned to me and said, “So you wanna do that interview now?” I needed a little time to set up. Erich Roland my director of photography put a red light bulb in the light on the side and used some red filters on his own lights. It gave us a red look. I asked Erich to give me a film noir concert look. I wanted deep shadows. This is something he’s very good at. Somebody is half in the light and half in shadows and it suggests a certain emotion of upheaval and mystery. Adding the red was the final touch.

How are magical moments captured on film when people know they are being filmed? Can you give specific examples?

Sometimes magical moments happen on their own and sometimes you have to set the stage so that if magic is going to happen there’s fertile ground for it to happen. I never work from scripts. I always make pages and pages of notes about what we could do when making a particular film. I often say I have enough notes to make 10 different films on the same subject. Once we get out there you need to be ready when the magic happens.

Magic can be positive and magic can even be negative. When I made “Saxophone Colossus” with Sonny Rollins we had already filmed him in concert in Tokyo, Japan doing his world premiere of his concerto for saxophone and orchestra. That was Sonny branching out and trying something totally different. He improvised throughout on his own themes the orchestra was playing. We wanted to get him with a more traditional jazz ensemble. We originally were going to film him on a boat sailing around New York City. I found out the cruise was at night and there weren’t any lights. They didn’t have sufficient power for our lights or camera batteries. We decided to film at Opus 40 in upstate New York on a sculpted rock quarry. He had the coating changed on his saxophone and it changed the tone of the instrument. When he got up to play he would play a vowel and out came consonants. Being a brilliant artist, he could build something around it. He was doing a brilliant concert but he was getting frustrated. Finally, he was doing solo improvising onstage and it was getting to him more and more. He jumped off the six foot ledge to stop it. It’s like he was having a musical nervous breakdown. He broke the heel of his right foot and fell back and just laid there. We were really concerned that he seriously injured himself. I ran to the other side to find out if he was o.k. Suddenly, he lifted the injured foot on top of the other and started playing as he was lying there. It’s a magical moment that was legendary in the jazz community before the film was released. We made it part of the film. He asked me to not use the music as they continued to play because his musicians were so upset they started playing the wrong changes. It still sounded great but he could hear what was wrong. That was a magical moment with positive and negative connotations. It was a situation that we were ready for.

Also, my wife and I produced “New Orleans Music in Exile.” Diana Zelman is my wife and she’s been my producing partner since 2005. We filmed in New Orleans two months after Hurricane Katrina hit, and the city was still quite desolate. We also filmed New Orleans musicians still in exile in other southern cities, specifically Memphis, Lafayette, Houston, and Austin. You could see the desperation and sadness on the musician’s faces when they gave us interviews or performed for us.

Going in with every artist you need to know where they come from, the kind of music they play, and the personality they have. Knowing this sets the stage for various possibilities.

Are there any Bluesmen you are itching to film and make a new documentary on?

I am always happy to work with my buddy Vasti Jackson. He has been in more of my films than anybody else. I forgot to mention I made a Blues film on my buddy Ted Drozdowski about his Midwestern tour with his earlier band Scissormen. I am so happy to see new young talent coming around like “Kingfish” out of Clarksdale. He is only 20 now and my wife and I saw him 3 years ago while we were in Cleveland Mississippi for the Grammy Museum opening. He knocked our socks off. He seems to be getting better and better. I would love to work with Tedeschi Trucks band. I almost worked with Derek Trucks a decade ago. Some projects get funded and others don’t. I just saw them perform on Jimmy Kimmel and they were tremendous.

What else do you want to accomplish?

I want my book to get published. I look forward to the re-release and the relaunching of “Deep Blues.” I hope it will have the same amount of success it had the first time around. There are more music films I want to make. I need to figure out where funding is going to come from.

One of the things that has often happened throughout my career is that I hook up with corporate funders like BMG Video, Sony, Britain’s Channel 4 Television, and Starz. Often there is synchronicity that happens when you hook up with the right funder at the right time. If the company is in need of programming and your interests are in sync, you are able to get a few projects out of them. When a company sets a new goal, I’m able to get several projects out of them before they suddenly realize they are spending too much money. That happened with Channel 4, BMG Videos, and Starz. When corporate goals change and they decide they’ve built up enough of a program library, they will put someone in charge who’s a care taker and doesn’t spend much money. As an independent producer you are always looking for the next wave to ride. Inevitably, the wave runs out. I am looking for the next wave I can ride.

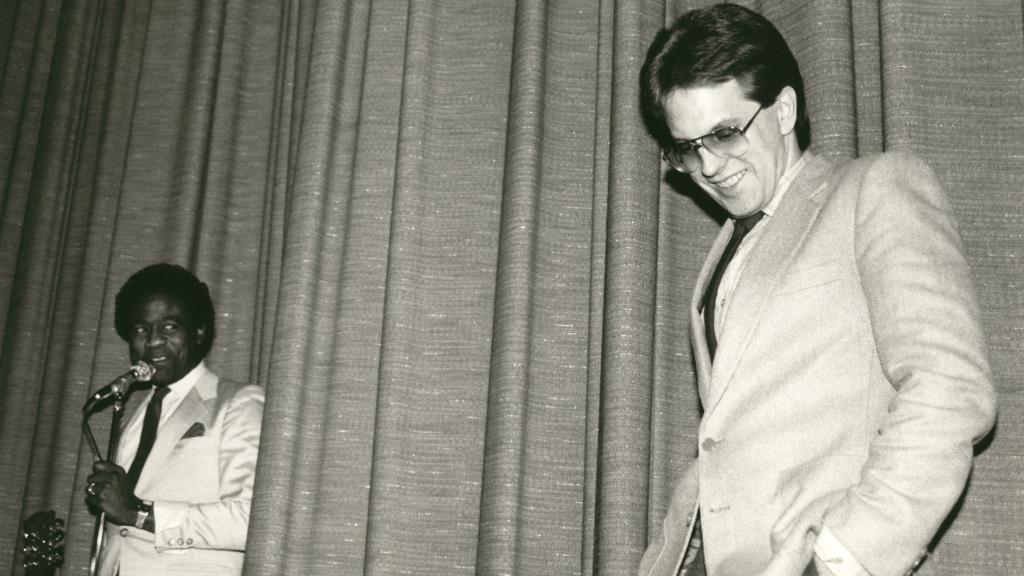

Robert Mugge

*Feature image Dick Waterman