The locus of psychedelia was San Francisco, where peace and love were the watchwords more so than anywhere else, and where Jack Casady was a first-generation member of the psychedelic rock that shaped the latter part of the ‘60s. Jack’s lifelong pal, Jorma Kaukonen, enlisted him as the bassist of this band he was in called Jefferson Airplane. You may have heard of them. So began the two musicians fine-tuning and blending their respective melodic styles like no band before or after them. And here they are 50 years later, still out on the road as Hot Tuna, working harder than they ever have at the techniques they’ve mastered, and which only they can bring out in one another.

Jack’s got stories. It’s worth noting that the stolen bass he refers to in our interview, the one that was returned 48 years later, was the one he played at Woodstock and on Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Chile.” The guitar was returned to him through a Facebook fluke. Jack posted a picture of him playing it at Woodstock, and what was just a spontaneous post became a stroke of luck when a man called him and said he had bought it years ago from a pawn shop.

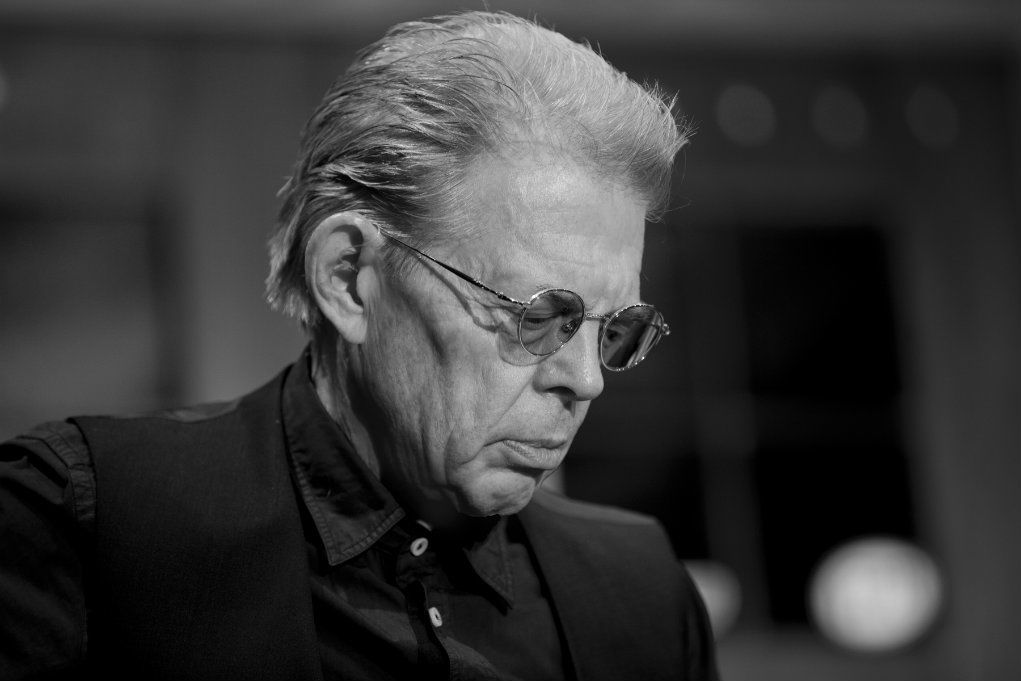

He speaks the same way he plays: with wisdom and authentic refinement. And at 75 years of age, Jack Casady still allows no grass to grow under to his feet.

ABS:

First of all, thank you for your time. Secondly, Happy Birthday!

Jack Casady:

Well, thank you. I’ve still got about 12 hours or so, here on the West Coast. Where are you located now?

I’m in Saint Pete, Fl — Tampa area, which you’ve played many times.

Yes. My mother used to go down to Sarasota all the time.

Oh, yeah. I used to live there. How was your big party? It was held at Levon Helm Studios in Woodstock, right?

Yes. On the 4th, we did Levon’s. On the 5th, we did Mount Tabor. And on the 6th, we did a Brooklyn show. I think I was presented with a cake every night at the show. I’ve now sworn cake off. And I’ve done five days of hiking — 25 miles. And I go for my traditional 30-mile bike ride on my birthday.

Wow. You’re putting me to shame. I just did my 45-minute walk on the trail today.

Oh, I like hiking. I’ve gotten into it a lot these past few years.

I do too. It’s just that Florida is kind of flat, so it’s boring.

You are absolutely right. It’s good for biking if you can keep your speed up and your revolutions up. But there’s nothing like hills to get it going.

I agree. Well, speaking of Levon, I know from reading Jorma’s book you recorded at his studio — and you were happy with his work because you were able to get the sound you wanted. I’ve read and heard really heartwarming accounts that serve as proof that he was a real champion of the underdog. I wanted your personal take on what it was like spending time with him at his studio.

He really was the best of the term of a “good ol’ boy.” He had a really humble upbringing. So the good fortune that came his way, I’m sure he was able to keep his head throughout, I think. And the things that happened to him in his personal life and his business life affected him. And you should read Levon’s book, as a matter of fact.

You know, that’s in my queue. I always have about 20 books queued up.

Exactly.

But that’s definitely one of them.

That would definitely give you a more personal understanding just like you had when you read Jorma’s book. He was always a gracious musician. He and I — I think we had as good a friendship as we could have under the circumstances of not seeing each other very often. But when we did see each other, it was an immediate comradeship of not only the art that we were both involved in, but wanting to present it in its truest form.

Right. I remember talking to Bob Margolin one time about how Levon really stood his ground, making sure Muddy and Bob didn’t get bumped from The Last Waltz. Certain band politics, I guess. I won’t name names. But I just thought that was so cool.

Yeah, I think you hit a kernel of where Levon stands. You know, I think that he’s the kind of guy — you make an agreement and you move forward. His understanding is everybody moves in a very open and fair manner. But of course in the business world, it doesn’t always happen. But aside from that, as a human being… We co-billed together on a number of shows and jammed together in that kind of circumstance. But I really felt that I knew him more as just another guy.

Yeah, he was just that guy.

He was so talented, of course. He was a great actor. I loved the roles he had and the way he played them. But also, he was just a very gentle and nice guy to be around.

You played on Roky Erickson’s Don’t Slander Me, correct?

I did. And that was really something, let me tell you. This is one of those deals, you know, Roky’s record company at the time — and I think it was the ‘80s.

Maybe early ‘80s.

Yeah, I think it was earlier. You’re right. Around ‘81 or something. I had my band, SVT, at the time. Jorma and I had taken a little break from Hot Tuna. He was doing some solo stuff and had a band called Vital Parts. One of the local musicians that I knew was hired to gather musicians together to do an album that was apparently contractually required for Roky to do. And Roky had a certain reputation of flying under the wire, so to speak. The producer put the band together. I thought it was good… “Oh, Roky Erickson, 13th Floor Elevators.”

Of course we knew him from the San Francisco days, and in the early days of the 13th Floor Elevators. He had such a tremendous voice. But apparently, he had taken a break from the cruel world of rock and roll and immersed himself into the religious world. And he came back out of that period of time. I think the producer was having trouble with him, because Roky of course had written a bunch of new songs and they were about his experience with Jesus. The producer was tearing his hair out, because the record company wanted to have more of Roky’s, as they call it, satanic devil music. He had eschewed all of that stuff.

So any case, it was really an interesting session, but we did end up doing a couple of songs that were more in the vein of what the record company really liked. I’m not sure how that eventually worked out, but I had fun doing the session. And I did it with Paul Zahl, my drummer with SVT. We had a great time.

Your Signature Epiphone bass is one of the most sought-after bass guitars. Dave Grohl and Gary Mounfield of the Stone Roses are just a couple examples of musicians who play it. Could you describe how and why you developed those exact specifications?

I’ve always had my hand in instrument development. The first two Guild basses that I had — the first one in 1967…

That got stolen?

That’s the one that got stolen. But Owlsley and I had worked and done the electronics on that. And there were carvings and it was really beautiful. But that, by the way, got returned to me 48 years later.

I know. I love that story.

And that is now going to be shown, along with my original Guatemalan shirt outfit that Jeanne the Tailor of San Francisco made for me, at the Woodstock Bethel Museum that is just about to open for this year. Anyway, I developed the instrument after a couple hollow-body guitars that took the Guild Starfires and revamped them with electronics. The first one with Owlsley, the second one with Ron Wickersham.

The first bass I had made from scratch turned out to be later on Alembic Company. It was Alembic number one. Rick turner did all the woodwork and the pickups, and Ron Wickersham did the electronics on that. So, I’ve always had a hand in that kind of stuff.

Well, in the mid ‘80s, while I was living in New York, there was a little music store called Chelsea Music right against Chelsea Hotel — West 23rd, between 7th and 8th Avenue. In there they had a hollow body Gibson that I had never seen before. It was a double cutaway, blonde goldtop Les Paul. I bought it, and it was a low impedance instrument. Les Paul played a low impedance guitar. Most of them are high impedance. I switched all my basses over to low impedance because there is a higher fidelity factor involved with that. I played that bass for a couple years with Jorma in Hot Tuna. I felt the pickups were deficient somewhat in fitting with modern music and having to compete with the clarity and the depth and tonality of a keyboard or something like that.

So, I approached Gibson about remaking the instrument. The instrument was only made –there was a short run in ‘72, I think, of about 600 instruments. And then they shut down the production. I love the instrument because, first of all, compared to the Guild Hollow Body Starfire it was a full scale. 34-inch rather than a short scale 32.5 inch — 31.5 inch, I think, with a Guild. And it was a true Hollow Body. The Guilds had a block down the center that went from the back to the top of the instrument.

On this Gibson, it was just a fluted piece glued on down the back side of the body, which left an open area between the top and back, which is a true Hollow Body. But it had different sonic characteristics that I really liked. I wanted to bring those out with the best pickups. So, I talked to Gibson and they weren’t interested. But since they owned Epiphone, they turned me on to Jim Rosenberg, who has since left Epiphone but was there the 20 years that I had dealt with him. Long story short, we developed and worked on the instrument.

And that was about 20 years ago, wasn’t it?

Yes, the 20th anniversary model came out in 2017. So, I went down to Nashville and worked with their pickup man, JT Riboloff, and I spent two weeks just going into the shop every day. We got all this together finally after about a year and a half.

And I got to tell you a story about my dear sweet late wife, Diana, who passed away six years ago. I was testing the instrument out, the prototypes. We finally got the prototypes working, and I had a Tascam 8-track recorder. Every time we got different batches of pickups, we would try them out and work with the prototype instruments before they went into production. And the one that I had played really sounded wonderful. I sent it back and said, “Ok, we’ll go into production.”

They went in and made the first production instrument. It came back beautiful, gorgeous, everything I wanted. But it just didn’t sound right, and it just drove us crazy. I looked over at my wife and I said, “You know, this isn’t right. Something’s wrong.” She said, “Jack, if it isn’t right, don’t ok it.” They were getting antsy; this had been 14 months now. And then we went over on the spectrum how they were putting it together, and measurements. We found out in the manufacturing process there was a miscalculation on the placement of the pickup by about a quarter of an inch, because they were measuring the placement of the pickup from a different point on the instrument than had originally had been designated. Once we figured that out, then they sent the second manufacturing run. And it was just perfect. It was a simple little fix, but it made all the difference.

I’m really happy with the instrument. I have two new ones right now. Every year that there’s a new production batch that goes out, I take them right out on the road and they go right into the band. And they are played in person, so I can keep track of the production quality and making sure that — any instrument that comes out there, if I set it up right and use the strings that I want and all that kind of stuff — it all sounds the way I want it to sound. So, that’s what happened with the anniversary model, which is a red one. I got two of them. We took them right out in 2017 and have played them for the last two years. They know that I don’t have a ringer out there. I’m really pleased. I’ve designed it so that engineers would love it in the studio, and it would place itself well in the track and not get buried in the mix because of a lack of any sonic clarity. So, I’m really happy, and by word of mouth it’s become to be a pretty good and dependable bass guitar.

So, you had the intent of other successful musicians picking it up? You must be proud to have been able to provide them with your special sound.

Oh, absolutely. The idea — my responsibility when I’m designing and have a say in that

manufacturing is this is not something they put in front of me and they copy my signature and put it on and put a couple of cosmetic things on it. You know? I really got into the nuts and bolts of the instrument so that I would stand behind it and put it out there as a unique sound and a dependable sound. And there’s plenty of manufacturers out there.

And Jorma’s got his M-30, so that’s cool.

Absolutely. Absolutely.

At the time you were joining Jefferson Airplane, was it more a leap of faith or an act of rebellion? I know you left college.

Well, I came out because of Jorma. I was on the East Coast working in bands and going to school. And he had just been asked to join the band eight weeks before, so it was just starting. So yes, in that case, it was a leap of faith. But it was also — I was 21 years old and I wanted to get away from that scene that was in DC that was not a scene where original music was encouraged. And it seemed like out in the West Coast it was. I came out and there was a certain amount of faith. I didn’t know what was before me at all. I had no idea what was really going on.

I love that it was you who convinced Grace Slick to join the band.

That was much later. Grace had her own band, Great Society. And all within the first couple years, the Grateful Dead, Great Society, Sopwith Camel, Quicksilver Messenger Service, The Charlatans… You know, had actually started before any of us. We were all starting out in ‘64, ’65, ‘66.

Did you have any idea the San Francisco sound would be as archetypal as it would later prove to be? You were so instrumental in its inception and fruition.

Of course not. That’s stuff that writers talk about. Musicians don’t talk about that sort of stuff. We didn’t know. We wanted bands. We were just trying to make music and see what would happen. At the time, we were just trying to do the nuts and bolts playing and writing songs and rehearsing, and putting together a unique sound. And that happens when you start to write your own stuff.

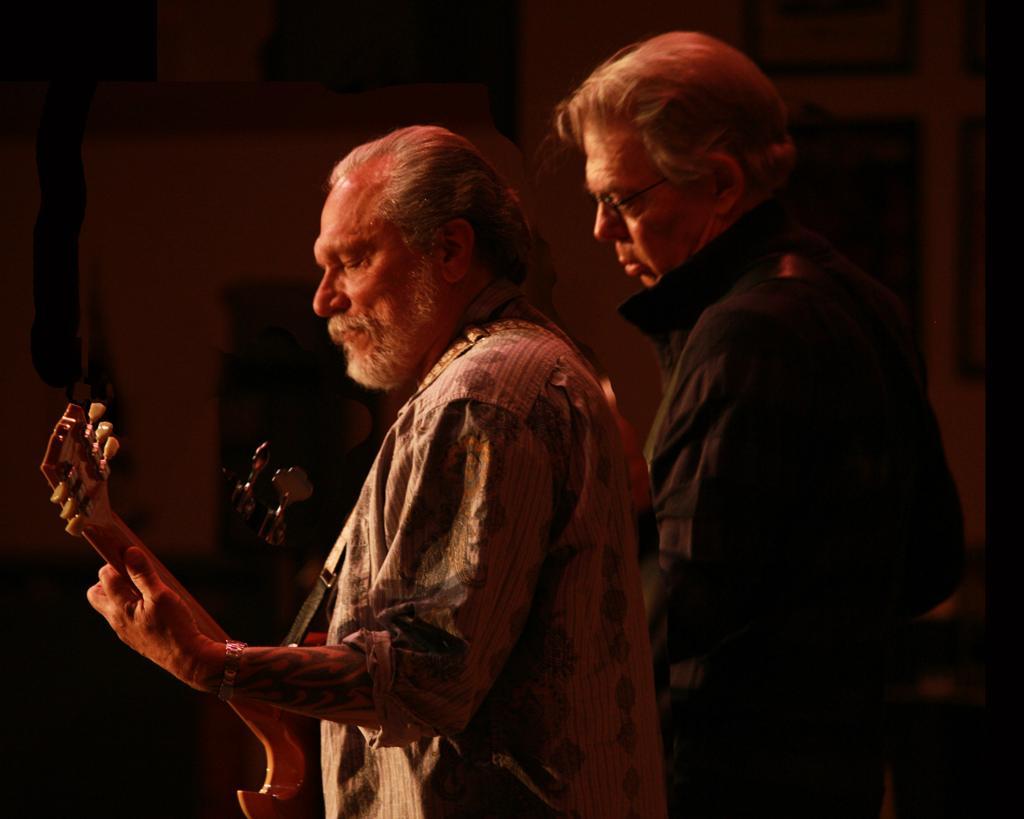

I know relationships in general take at least some degree of work or maintenance, but would you say it’s the unyielding friendship you’ve always had with Jorma that has held up the equally resilient musical bond?

The short answer: yes. We’ve known each other — we first played together 61 years ago, when I was 14 and he was 17. At that time, we were still in high school. We didn’t seriously think that would be our life’s career. By the time I was 15 or 16, I knew that was pretty much what I wanted to do. And a couple years later, I’m sure that Jorma did too. But I think the bond between he and I is a love of music and appreciation of the same kinds of music.

The art of making music we both honor and try to live true to. And I think when we see each other, we see us each trying to do the best we can. We try to be good at what we do, but not at the expense of our soul. We try to be true to our art form and true to ourselves. The friendship is something beyond that. Because a lot of bands come together and they form business friendships or friendships because of the band. And then later on maybe they have difficulties. Jorma and I, I don’t think we’ve ever had an argument.

We stopped playing for a couple years together just because I think we needed a break. But you know, Jorma says, “We never really broke up. We’ve always gotten along because we’ve never had a band meeting.” The reference points go back to our childhood, just being teenagers growing up and visiting each other’s family and all that. And I think that gives you a perspective that isn’t just oriented around the band that you’ve put together and the business aspect to it all. When we go on stage, we really try to play the best we can every single night. It’s not about the night before, it’s about that night and the night coming up.

It seems in your collective stage presence that you have the kind of relationship where you both can read the other’s mind yet can still be surprised and entertained with one another.

The object of playing well together is not about predicting what the other person is going to do; it’s about listening to what each other is doing in the present and reacting to it. That’s what keeps you so alert and in the moment of the music, I think.

And you guys just don’t get tired of each other.

No. I don’t think we get tired of each other, because we work so hard at it. It’s like any relationship. You’ve got to work at it. And you’ve got to infuse it with the best effort you can, not the path of least resistance.

Right. Right. So, how do the acoustic shows compare to the electric trio format with Steve Kimock?

It’s a different approach. It’s a different sonic approach and a different technique involved. When Jorma is playing the acoustic guitar, it’s not his electric unplugged. He’s a true acoustic guitar player. There are different sensibilities and techniques that he’s using that is not applied to electric guitar work. Most of the career, I’ve played electric guitar without acoustic guitar. These last few years with the Tom Ribbecke Diana bass that I had made in my wife’s name, it’s a true acoustic bass guitar. And I can now work in that sonic world of the acoustic guitar.

Jorma is a finger picker; he’s not thrashing or playing chords to accompany his singing. Now in the electric world, it’s different. You’re using different rhythmic aspects. There’s combination bass and drum stuff going on, along with the melodic work against Jorma’s fingerpicking. But it’s on an electric instrument. That’s a whole different approach to the music, so it really steps into a different world. And we don’t think about comparing them at all. It’s just you do one world, and you do the other world. And once in a while, we have guests that come in. The trio is the basic format, but we’ve worked with a lot of musicians on stage. These last few years, again, we’ve kind of revived the trio format with occasional visits from Steve Kimock and other people too.

What is it about Jorma’s finger-picking style that truly empowers your own melodic style and brings out the best in your playing? Because I just don’t see that chemistry happening with

anybody else.

Well, that’s it. The compositional aspect of Jorma’s work that is implemented with the thumb and the two fingers on the finger style compositions — because that thumb is working back and forth, that rhythm is going. And its basslines are going along with the partial chords and melodies there, all within that complete music. And that means I can move in the bass world from a supportive role to a melodic role doing various things in unison, to playing melodic harmonies off of certain notes that he’s doing and singing in the song. That’s coming back to more roots playing, so I can move in and out of the world.

It’s kind of like in an orchestra. You can go through the bass range up to the cello range and then come back down again. And that’s what I try to do. But you know, when I play with other people. I can’t use that kind of format.

Yeah, and I was actually going to ask you that. When you are in the process of composing basslines, is it the structure of classical music that is preponderant throughout your writing process? I know you like jazz and folk tones.

Right. You try to do the right thing at the right time with the right people. I’ve done some shows with GE Smith, and what I’ll be playing with him will be pattern playing, repetitive pattern playing. That’s the kind of songs he usually chooses, and that’s the role of the bass in that instance. But when I’m doing stuff with Jefferson Airplane, I’m doing stuff with a lot more melody to some of the things, a lot more moving basslines.

But at the same time, I wanted to drive the whole band and make sure there’s a good low end drive. I just didn’t want it to be monotonous and repetitive in that instance. With Jorma, I can really open up the most in some of the compositions like “Sleep Song.” Something where I can move in these nice, delicate melodies, and at the same time the song doesn’t lose the drive while you’re playing it. So, I’m fortunate that I’m able to work in that world and develop the style that I do.

I know you teach at Fur Peace Ranch. I’m interested in knowing what your latest master class is, or what you’ve got planned for future classes or workshops.

I did the opening session. We call it Double Dose, because we’ve been doing it the last few years where we will teach the bass players and guitar players. It’s one thing to learn on your own separately, but the whole idea of the bass player is to play with somebody. Although, Jorma can see guitar players as standalone performance. But Double Dose was set up so that we would have sessions the third day of teaching where we would have them pair off with a bass and guitar and actually work on the craft of playing together.

So, you can learn the notes and the techniques and the song and the chord changes and the time you’re supposed to do all this different stuff. But there is a whole other element that comes in of learning how to play with somebody else, to listen to the other person, to make space for that other person, and listen and craft the fact that you two are going to make a third entity.

That’s a great way to teach. What has teaching taught you? For lack of better words.

It humbles me and my own craftwork and knowledge, and requires me to investigate if I don’t know how or why I do something. I had better investigate it and break it down myself and put it back together, so that I can teach it to somebody else.

It’s stimulating in that way.

Absolutely, it’s stimulating. And I think it has played a huge and important role in Jorma and I’s development these past 20 years of playing together, individually and playing together.

That’s awesome. Lastly, I want to congratulate you on 50 years of Hot Tuna.

Well, thank you.

Do you have any final words for me as it relates to this impressive milepost?

No. You know, I’m really just so blessed to have this arena to work in that I can — Jorma and I are working harder than ever, you know.

I can see that.

And we’re involving ourselves harder than ever, and it’s very gratifying. You know, all my early heroes that were older musicians in the jazz and classical world, they all did some of their best work later in their life. There wasn’t just great work when they were young and then they all died out like in the rock and roll world. I really don’t think of myself as a rock and roll musician; I think of myself as a musician that always wants to get better at what he does.