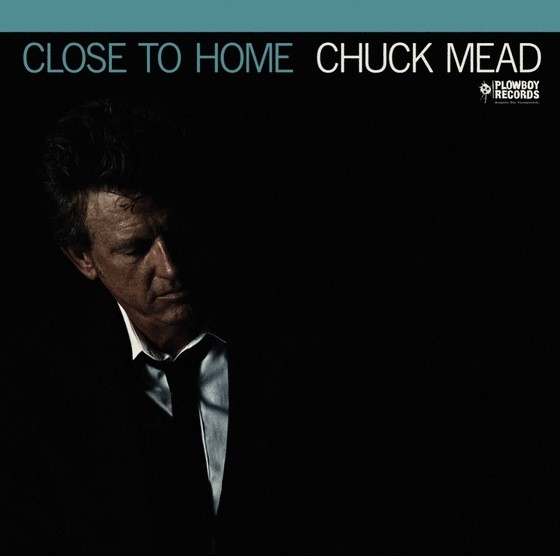

Neo-traditional honky tonker Chuck Mead serves up a Memphis-spiced hardcore country platter with Close to Home, due for release on June 21st, 2019. The 11-track collection, on Nashville independent label Plowboy Records, is the follow-up to Mead’s first Plowboy release, 2015’s Free State Serenade. Recorded at the historic Sam Phillips Recording Studios in Memphis, Tenn., the album was produced by acclaimed Memphis recording engineer and producer Matt Ross-Spang.

“It’s probably the least-country record I’ve ever made,” Mead says, “but at the same time, it’s really a country record.”

Mead has been upending expectations and walking the line between hardcore country music and raucous rock ’n’ roll for the better part of 25 years. As a member of the alternative country music quintet BR5-49 in the early 1990s, Mead fused rock ’n’ roll excitement with the soul of the Music City’s honky tonk heritage, sparking the rebirth of Nashville’s Lower Broadway music scene. Over the course of the late ’90s and the early 21st Century, he recorded seven albums with BR5-49 and spread the gospel of neo-traditional country music around the world, garnering the band a CMA Award for Best International Touring Act and three Grammy nominations.

Mead subsequently released three well-received solo albums and served as the Musical Director/Supervisor/Producer of the hit Broadway musical Million Dollar Quartet, as well as the companion CMT dramatic series, Sun Records. The time he spent in Memphis during the production of the TV series led to Mead’s change of recording venue for his new album.

“I really delved into the Memphis music scene when I was living there for four months,” he says. “I wanted to get as many local Memphis musicians to play in the series as possible. I got to know a lot of people in the scene, and I’d known producer Matt Ross-Spang for quite a while. When the Million Dollar Quartet show was on tour, we came through Memphis a couple of times. At night the cast would record at the original Memphis Recording Service (better known as Sun Studios) and that’s where I first met Matt. He was very young but was the head engineer and really brought the old studio back into shape. I started hanging out with him, and he kept talking to me about cutting a record in Memphis.”

By the time Mead was ready to record, Ross-Spang had earned a reputation as one of the top engineers and producers in the Americana and roots music scene, and had moved from Sun to Sam Phillips Recording, the Memphis studio built by Sun Records head Phillips in 1960. Ross-Spang, hailed by Rolling Stone as “one of the most trusted arbiters of the modern Memphis sound,” has worked with a who’s-who of roots artists, among them 61st Grammy Award nominees John Prine, Jason Isbell and Margo Price. He notched the Grammy for engineering Isbell’s The Nashville Sound (as he did for 2015’s Something More Than Free); co-produced Price’s stunning debut, Midwest Farmer’s Daughter, and sophomore effort All American Made; and engineered Prine’s The Tree of Forgiveness.

“I’ve recorded in some cool Nashville studios like the Quonset Hut, RCA Studio B, and The Castle,” Mead says. “But there was something almost supernatural about working at Phillips. You could feel Sam’s spirit.”

Grinding traditional musical forms together and watching the sparks fly was an integral part of Phillips’ genius and the “Memphis Sound.” The process led him to create transcendent and transformative records from Howlin’ Wolf, Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, and many others, a tradition continued by producer Ross-Spang.

“Matt wanted me to make a bigger record,” Mead says, “something that was out of my box and I was all for it. So I turned it over to him and he took things in a direction I didn’t foresee.”

The opening track of Close to Home — the grungy, hillbilly rocker “Big Bear in the Sky” — exemplifies one of those unexpected directions. It’s a song Mead describes as “Johnny Horton fronting the Sonics.”

“The song is based on a Mi’kmaq Indian folk legend about the Ursa Major constellation,” Mead says. “I wanted it to be a Johnny Horton-style history ballad. I had recorded an earlier version for an anniversary album for the German reissue label Bear Family Records, but it wasn’t quite where I wanted it. I wanted to rock it out in the studio and Matt pushed me to take it to an entirely new level.”

Another unexpected musical turn can be found on the workingman blues of “I’m Not the Man for the Job.”

“My drummer, Marty Lynds, describes that song as ‘rocksteady from San Antonio,’” Mead says. “If you look through record stores in Jamaica, they carry a ton of country music, so rocksteady and reggae are not that far apart from country, but there’s also some Doug Sahm Tex-Mex ingredients in the song too.”

Another tune, “Tap Into Your Misery,” takes the form of a classic traditional country song and was co-written with legendary award-winning producer/songwriter Brent Maher (The Judds, Carl Perkins, Ike & Tina Turner).

Then there’s the title track, which Mead allows is “pretty heady for a country song,” explaining that “it’s about those weird instances where you think of a person or mention them and suddenly they present themselves. Or maybe you’re experiencing some sort of event in your life and suddenly there is a book or a song or movie that lines up perfectly with the situation. It’s not quite synchronicity … But it’s something that makes it seem there’s some cosmic frequency that we’re all on and the possibility that there is some sort of order to the universe.”

The spirit of adventure and musical exploration continues throughout Close to Home. Mead delivers pre-rock hillbilly strut with “Better Than I Was,” rocks out with the Chuck Berry-style lyrical acrobatics of “The Man Who Shook the World,” navigates the Louisiana-swamp rock groove of “Shake,” and scuffs up the sawdust of Texas honky tonks with the outlaw country-tinged title track “Close to Home.” No matter where his muse takes him, the glue holding the album together is the solid honky tonk foundation of Mead’s signature sound.

“I really wanted to make a record that was a little bit different from what I had been doing,” Mead says. “Looking back, I really have done that on every record I’ve made, because why make the same record every time?”

Chuck Mead

*Feature image Joshua Black Wilkins