Dick Waterman just may be the most knowledgeable man on the history of blues. After all, he advanced that history in more fundamental ways than any person alive today. Alan Lomax may have chronicled the music of the Delta progenitors in his field recordings, but Dick Waterman, beginning in the mid-60s with Avalon Productions, sought out the originators of the genre, pulled them out of “retirement” and presented them to a folk audience that to that point considered blues to be a footnote in the American musical history.

Waterman’s first movement on the chess board was rediscovering the most important blues man alive at that time, Son House. And for the next half century Waterman as an agent, journalist and photographer became the bridge between some of the most important artists in blues and the ever-increasing blues fan base.

He reveals his amazing story in A Life in Blues, a new biography written by Tammy L. Turner who spent four years and did more than 40 interviews with a man who had dedicated his life to the careers of Son House, Mississippi John Hurt, Skip James, Junior Wells, Buddy Guy and Bonnie Raitt. Their economic survival depended on Waterman’s getting them gigs. But he’s also a Boston College journalism graduate, and he’s able to take his photographic memory of his experiences with these artists and translate them into words that take you there.

If you don’t believe it was Son House and not the devil who gave Robert Johnson his muse, you will after reading Waterman’s biography. “With Son there was only one way to do it. That was the way he was born to perform,” recalls Waterman. “When he started a song and he backhanded across that steel bodied National (guitar) and ripped that slide on, he emotionally just went somewhere else. His eyes closed, and the sweat broke out on his face, and his face contorted.

“He just went into a whole other world, and he stayed there as long as the song manifested itself. It could be eight minutes or 10 or 12 minutes, whatever, and then when the song ended, he’d run his head back and open his eyes, and he came back to you. It was like he had left you and went somewhere, and now he came back to you, and he would take a handkerchief and mop his forehead and say, ‘That was just a little old piece of blues, and I hope you liked it.’ And that wasn’t an act. He just thought it was a small offering, and he hoped that you liked it.”

Waterman recalls his first contact with musical scholar Tammy Turner. “When she came to me and said she wanted to do a biography of me, I really made light of it. I didn’t think that my accomplishments had been very meaningful or had had much impact, but she really wanted to do it and spent three or four years doing many, many interviews. She did over 40 interviews, and so I have to give her credit for seeing there was a book where I myself did not.”

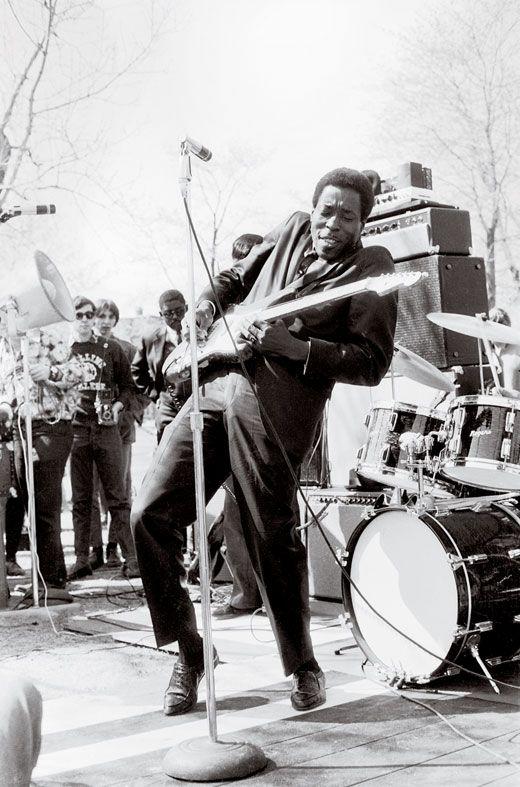

And what a book it is! Waterman was there when B.B. King crossed over to a white audience at Fenway Park in Boston in 1968 performing at a Eugene McCarthy political rally. Waterman presented Son House at the Ann Arbor Blues Festival, blues’ answer to Woodstock, in 1969. He marshalled Bonnie Raitt’s rise from a Radcliff student to a rocking blues phenomenon in the 1980s, and he convinced Buddy Guy to go on the road in the late ’60s.

Waterman recalls walking into the auto repair shop where Buddy Guy worked in 1967. “I went in and he was (working) on a car with hook-up tracks, and the engine block was up in the air swaying, suspended by a small chain. I realized that if that chain broke, that would be the end of his career as a guitarist, and I said to myself, ‘I’ve got to get him out of here.’ He was working under some dangerous situations, but he liked it. He was good at it, and he thought it was an honest way to make an honest living. So, he didn’t have a real burning desire to get away from it because he liked it.

“He knew that (his occasional performing partner) Junior was out on the road. I took Junior out in ’66, and this was ’67. So, he was already out on the road for me, and was making good road money and was being treated well. So, in other words, he didn’t need any reference. Junior was already working for me.”

Buddy Guy had performed on Junior Wells iconic Delmark Hoodoo Man Blues album as “Friendly Chap,” but they did not often play together in Chicago in the clubs.

“Buddy was married with kids, and Buddy went home at night. In other words, Buddy was either in the Chess studios or at home at night with his wife and kids. Junior liked to go out to the clubs. Buddy did not. Buddy would come out and play, but Buddy never went out just to play like Junior did.”

Like Forest Gump, Dick Waterman has always been where the tipping points are in blues. He introduced Eric Clapton to Son House. He was backstage when Howlin’ Wolf became the first electric bluesman to perform on national television with the Rolling Stones on Shindig in 1965. He accompanied Bonnie Raitt on her tour with the Rolling Stones. He has photos of Joan Baez with Bob Dylan when they were going together. Most significantly, he was prescient enough to realize that if he could find some of the original blues creators during the folk boom, he could resurrect their careers and take them to new heights in front of a burgeoning youth mass market.

Dick Waterman will be my guest at the ninth annual Call and Response Symposium at the 34th annual King Biscuit Blues Festival on Saturday, October 12th at the Malco Theater in Helena, Arkansas from 12:00 to 1:00.