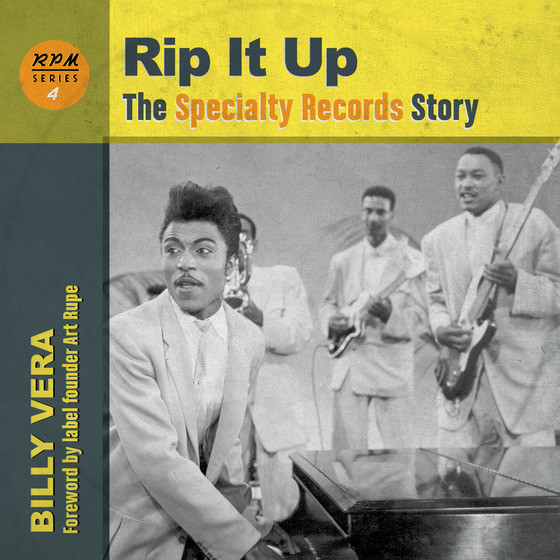

On November 5, 2019, BMG Books will publish Rip It Up: The Specialty Records Story by Billy Vera, with a foreword by 102-year-old label founder Art Rupe. The book is the fourth installment of BMG’s RPM Series, which focuses on pioneering record labels.

Launched in the mid-1940s, the Los Angeles-based Specialty Records emerged as one of the most important independent labels for African-American music in the 20th century. Recognizing that competing with major record companies was a losing battle, founder Art Rupe headed to Central Avenue, cultural center of L.A.’s black community, where he spent $200 on what were then known as “race records.” He carefully analyzed each, developing his own formula for a successful venture.

Soon, Specialty was scoring R&B hits with artists such as Roy Milton, Camille Howard, Jimmy and Joe Liggins, and Percy Mayfield. Drawn to the music of New Orleans, Rupe went on to sign Lloyd Price, who topped the charts with “Lawdy Miss Clawdy.” It was through Price that Specialty acquired its best-known artist, Little Richard. After “Tutti Frutti” exploded in 1955, Richard and the label scored a string of successes: “Long Tall Sally,” “Lucille,” “Keep A Knockin’,” “Good Golly Miss Molly,” and more.

Rip It Up: The Specialty Records Story offers a definitive history of the legendary label.

PERCY MAYFIELD – THE POET OF THE BLUES

One day in the summer of 1950, a thirty-year-old songwriter “just walked in the door of our Venice Boulevard office one day,” according to Art Rupe, and asked to play his songs. The composer in question was Percy Mayfield, who had done a session the previous year for Al Patrick’s Supreme Records, a few words about which are in order here.

Two of the four songs on Mayfield’s date for Patrick would go on to some degree of renown in the future: “Two Years of Torture” wound up on Ray Charles’s The Genius of Ray Charles album and on Lou Rawls’s 1989 comeback album, At Last, and “Half Awoke” was later recorded by B. B. King under the alternate title “You’re Still a Square.”

In less than two years in business, Supreme scored a number-one smash with Jimmy Witherspoon’s “Ain’t Nobody’s Business,” along with the number-two R&B and number-six pop hit, “A Little Bird Told Me” by Paula Watson. Another Supreme act, Eddie Williams and His Brown Buddies, recorded the original version of “Saturday Night Fish Fry,” written by the group’s drummer, Ellis “Slow” Walsh, and pianist, Floyd Dixon. The song was turned into a blues standard by Louis Jordan and His Tympany Five. Not bad for a little indie label owned by a black dentist with no musical training.

It wasn’t long, however, before Supreme was out of business. One reason given for the bankruptcy was a rather expensive and quixotic lawsuit against Decca Records regarding Evelyn Knight’s Top 10 cover of “A Little Bird Told Me.” The popular tune was also covered by Blue Lu Barker on Capitol and Frank Sinatra on Columbia.

Floyd Dixon later informed me that “nobody got a quarter, and Patrick ended up owning a number of office buildings downtown,” reminding us of New Orleans R&B star Paul Gayten’s sadly famous rejoinder, “Nobody fucks the black man like a black man.”

Rupe may or may not have been previously aware of Percy Mayfield when he walked in off the street that day, but as a song man who loved a good lyric, there is no chance he could not have been impressed when he heard the first verse of Percy’s song,

Heaven please send to all mankind Understanding and peace of mind But if it’s not asking too much Please send me someone to love

In that moment it was clear to the record man that here was a songwriter, a poet of the blues like no other. And this was no fluke, either. In song after song, the poetry of Percy’s words of pain, loss, hopelessness, suffering, despair, and madness struck home to anyone with ears to listen and a heart to hear.

Four days after the singer’s thirtieth birthday, Rupe took him into Universal Recorders with a band led and arranged by Thomas Maxwell Davis, who also took the tenor saxophone solos. Maxwell Davis was the top R&B arranger in town. His charts decorated recordings by artists of the caliber of Dinah Washington, T-Bone Walker, Charles Brown, Amos Milburn, and B. B. King on labels like Mercury, Imperial, Aladdin, and Modern, and they add many beautiful colors to Mayfield’s songs.

Years later, at a Christmas party one night, I was approached by Bob Dylan, who said he wanted to thank me for reissuing the two Specialty CDs I produced of Percy’s material. We spent the next two-and-a-half hours chatting about the poet’s art while Dylan not too politely blew off one after another of the A-list celebrities who came over to kiss the ring until, at one point, he simply stood up, shook my hand, and said, “Startin’ to fade, man. Gotta split.”

Barry “Dr. Demento” Hansen, who headed Specialty’s reissue department in the early 1970s, hit the nail on the head when he rightly compared Percy’s subtle emoting to that of Billie Holiday in his liner notes to the album of Mayfield material he produced. When it comes to phrasing, I’d rank him on a par with Frank Sinatra.

Percy’s song, “Please Send Me Someone To Love,” reached the top spot on the Cashbox and Billboard R&B charts and number twenty-six pop and has been the subject, over the years, of cover versions by Dinah Washington, B. B. King, Nancy Wilson, the Moonglows, Dale Evans, jazz organist Shirley Scott, saxophonist Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, and even actress E. G. Daily, the voice of the character Tommy on the children’s cartoon series Rugrats. Other artists who have recorded Percy Mayfield songs include Elvis Presley, Mose Allison, Little Junior Parker, Stanley Turrentine, Lou Rawls, and me.

The reader may have seen elsewhere that this record sold “over a million” copies. All we can say is beware of statements by fans who write articles. Hyperbole and speculation aside, the actual sales figures in Specialty’s files, dating from its release date of September 1, 1950, to October 31, 1952, were 294,887 78-rpm and 1,750 45-rpm records, which are still impressive numbers from an era when the average number-one R&B hit sold in the neighborhood of 100,000 pieces. The 45-rpm speed, introduced by RCA Victor in April 1949, was still new to customers of rhythm and blues. By contrast, the follow-up, “Lost Love,” at number two, sold 110,682 78s and 1,295 45s during roughly the same period. Percy’s next four releases, “What A Fool I Was,” “Prayin’ for Your Return,” “Cry Baby,” and “The Big Question,” all Top 10 hits, sold between 20,000 and 40,000 each, which shows how few copies a record had to sell to make it that high in those days.

Born in Minden in northern Louisiana on August 12, 1920, to Penn and Adis Mayfield, Percy, according to some long-forgotten copywriter at an advertising agency called Michael Brand Associates in a 1950 press release aimed toward “Negro publications,” “wrote creative poetry while still in high school. In the Parish Training School, Webster, Louisiana, Percy obtained a thorough grounding in musical composition. Coming to California in 1941, he made guest appearances with a number of orchestras, winding up with a two- year engagement with George Como’s band.” He also supported himself via activities as varied as shining shoes, pressing clothes, and hustling pool.

The hits continued until 1952, when he was involved in a tragic automobile accident, which deeply scarred his once-handsome face and seriously affected his self-esteem. Despite some fine subsequent recordings, including “Loose Lips” and the amazing “Memory Pain,” he never again charted for Specialty, leaving the label—for the first time—in 1954. The following year, he was scuffing again and headed for Chicago, where he did one session for Chess, resulting in the single “Double Dealing,” and wrote a song for former Specialty label mate Camille Howard, “Business Woman.”

In 1958, with Ray Charles, he wrote “Tell Me How Do You Feel,” recorded by the Genius on his final Atlantic singles date. Several flops on Cash, Imperial, and 7 Arts, as well as two brief returns to Specialty, rounded out the fifties, and Percy moved back to Minden, where he’d purchased some property during his gravy years.

A series of correspondence between Percy and Art reveals the desperate straits in which Percy found himself in the early 1960s. In a letter dated January 26, 1959, he thanks Rupe for a small advance against future royalties and asks to record again for Specialty. “I had glamour to help my appearance in those days, now I don’t have, so, ugly as I am and as bad a shape as I’m in financially . . . .” Although Art was, for all intents and purposes, out of the record business by then, he relented a year-and-a-half later and did a session with the artist, resulting in one single.

The record didn’t sell, and on August 25, 1960, Percy sends this telegram: “Sorry to bother you but my strain is as I wrote you . . . .The people I owe want their money. Please get me out of this strain, Pappy [his pet name for Rupe]. I’m still depending on you.”

On October 5 Art writes, “To say that I am truly sorry for your plight isn’t enough to help solve your problems, but I’ll do what I can. The record business is rougher than I have ever seen it. Your record probably won’t make it—but we may gamble another release soon.” He goes on to say he is releasing the artist from his contract and encloses some money, saying, “A check came in today on one of your songs, and I know you could use the money. So we are sending you $300.00.”

During that period, Percy wrote songs for an imagined stage musical and taped them on a home recorder, sans musicians, and submitted them to Rupe for his consideration. In 1989, when I was employed by Specialty, my trusty engineer, Gordon Skene, found the tape. One of the songs, recorded a capella by just Percy and an unnamed female vocalist, was “Hit the Road, Jack.”

In April 1961 Percy writes, “I will always be grateful for your guidance and your friendship. If I ever amount to anything again . . . I have you to thank for it.”

A year after sending Rupe the tape, Percy was signed as a staff songwriter to Tangerine Music, the publishing entity owned by Ray Charles. The song became Ray’s biggest-ever hit and continues to be a big earner for Percy’s estate and that of Ray Charles.

Meanwhile, back in 1952, as Percy lay recovering for five months at Kaiser-Fontana Hospital in Fontana, California, a benefit was being held at the Lincoln Theater in South Central Los Angeles on October 9, hosted by local disc jockeys Hunter Hancock, Ray Robinson, Charles Trammell, and Joe Adams. The latter would figure in Percy’s later career as Ray Charles’s manager when Mayfield served as a staff songwriter for Ray’s Tangerine label. There he penned songs for Ray (“But on the Other Hand, Baby,” “At the Club,” “Danger Zone,” “Hide nor Hair,” the previously mentioned “Hit the Road, Jack,” among others) in addition to recording two brilliant albums of his own, My Jug And I and Bought Blues, along with one chart single, “River’s Invitation,” a remake of an earlier Specialty release with a more up-to-date arrangement by Gerald Wilson.

After I moved to Los Angeles in 1979, Paul Gayten brought Percy to my apartment one afternoon. We got to know each other pretty well, and I wound up recording his song, “Strange Things Happening.” One thing that struck me was the way he would speak in the same poetic way he wrote, filled with metaphors and odd allusions. He told me how he would customize material for Ray: “See, I’d put in little references, like ‘You know I’m hooked on you, Mama,’ because, you see, Ray had a habit at the time.” Ray’s heroin addiction has been well documented. Another such reference comes in “Hide nor Hair,” when Ray sings about one Dr. Foster—based on a real character—who steals his woman, “’cause he’s got money and medicine, too.”

Post-Tangerine, the late sixties and early seventies found Percy recording one album for Brunswick and three for RCA Victor as well as a 1974 Atlantic single, “I Don’t Want to Be President,” produced by Johnny “Guitar” Watson that reached the lower rungs of the charts.

Percy Mayfield passed away one day shy of his sixty-fourth birthday. His funeral was well attended by the LA blues community, including Etta James, Lowell Fulson, Bumps Blackwell, Lee Allen, and Paul Gayten, who drove my daughter and me in his Rolls Royce. Little Richard sang “Amazing Grace,” and more than one woman made a scene at the sight of Percy in his open casket.

The last word, appropriately, comes from Art Rupe, who had tremendous admiration for his great artist’s gifts, stating his belief that “[h]e was uneducated but highly intelligent. If he could have been encouraged more, he would have been seen as great as Langston Hughes.”

Pre-Order Rip It Up; The Specialty Records Story