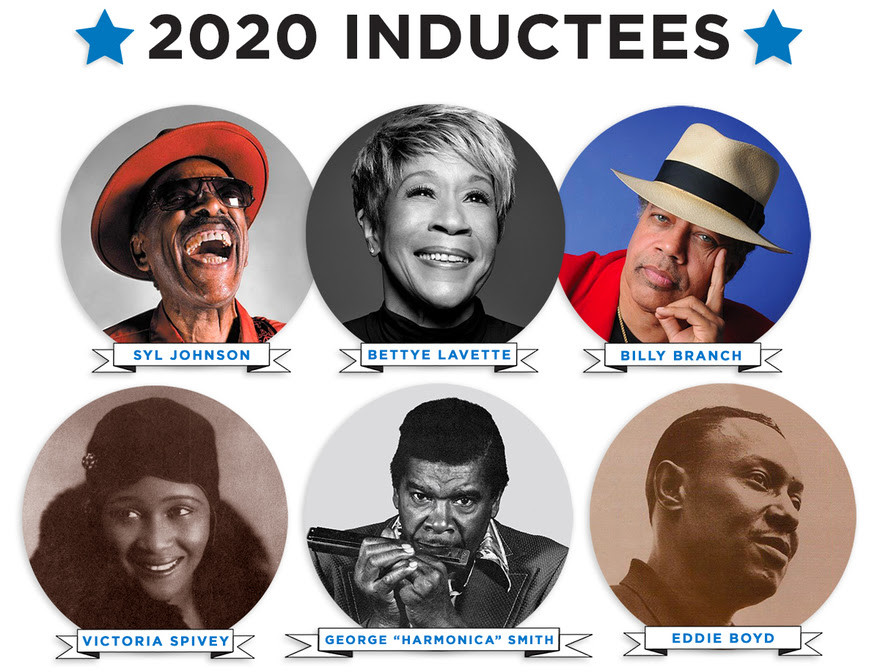

The 14 honorees of The Blues Foundation’s Blues Hall of Fame’s 41st class encompass nearly a century of music, spanning from 1920s stars Victoria Spivey and Bertha “Chippie” Hill to contemporary luminaries Bettye LaVette, Syl Johnson, and Billy Branch.This year’s inductees in the Blues Hall of Fame’s five categories — Performers, Non-Performing Individuals, Classics of Blues Literature, Classics of Blues Recording (Song), and Classics of Blues Recording (Album) — also vividly demonstrate how the blues intersects with a broad variety of American music styles: soul, funk, country, R&B, and rock ’n’ roll.

The new Blues Hall of Fame performers aren’t just exceptional musicians, but they also are educators, innovators, entrepreneurs, and activists determined to leave their mark on the world.

Piano-man Eddie Boyd scored several hits in the early ’50s (most notably “Five Long Years”) for Chess Records, but the outspoken Mississippi-born Chicago bluesman, dismayed over racial injustice and record business chicanery, left America in the mid-’60s for Europe, where his career prospered for several decades. Harmonica ace Billy Branch, part of the “New Generation of Chicago Blues,” is a multiple Blues Music Award winner who also has taught hundreds of blues classes around the globe and is a two-time recipient of the Keeping the Blues Alive Award in Education. Powerhouse singer Bettye LaVette finally achieved her much-deserved acclaim in the new millennium after several decades of struggles within the industry, garnering many honors — including several Blues Music Awards — and performing at President Obama’s 2009 inauguration celebration.

Victoria Spivey may be best known to general music fans for including a young Bob Dylan on a 1962 recording session; however, her unparalleled 50-year career began with her breakout tune, “Black Snake Blues,” and included her roles as songwriter, manager, bandleader and label owner. Guitarist Syl Johnson (brother of Blues Hall of Famer Jimmy Johnson) starred in Chicago’s soul scene during the ’60s and ’70s. His funky, often politically charged blues-fueled tunes (like “Different Strokes” and “Is It Because I’m Black”) have made him a favorite for sampling among hip-hop artists. The enigmatic George “Harmonica” Smith, who played with legends like Muddy Waters, Big Mama Thornton and Big Joe Turner, has been widely hailed by blues aficionados and musicians as one of the premier blues harmonicists, and influenced a generation of west coast harp players.

The revolutionary producer Ralph Peer, 2020’s honoree in the Individual (Business, Media & Academic) category, is most associated for his formative recordings in the country music field, but he first did pioneering work in the blues world (including co-producing the Mamie Smith historic 1920 “Crazy Blues” session). Entering the Blues Hall of Fame as a Classic of Blues Literature is Earl Hooker, Blues Master, the insightful biography of the blues guitar giant (and 2013 Hall of Fame inductee) written by French writer/producer/translator, and American roots music authority, Sebastian Danchin.

Howlin’ Wolf: The Chess Box is 2020’s Classic of Blues Recording: Album, the latest BHOF honor for the seminal bluesman. There are five Classic of Blues Recording: Singles receiving Hall of Fame induction: Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s original recording of “That’s All Right (Mama),” later made famous by Elvis Presley; Bertha “Chippie” Hill’s 1926 hit version of the oft-recorded “Trouble in Mind”; “Future Blues,”an exemplary example of Pattonesque blues by early-Delta bluesman Willie Brown, and two tunes from the early ’50s — “3 O’Clock Blues,” B.B. King’s first breakout song and No. 1 R&B hit in 1952, and Ruth Brown’s remarkable rendition of “Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean,” 1953’s best-selling R&B record.

The Blues Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony, held in conjunction with Blues Music Awards Week, will occur on Wednesday, May 6, 2020 at the Halloran Centre at the Orpheum (225 S. Main St., Memphis). A cocktail reception honoring the BHOF inductees and Blue Music Awards nominees will begin at 5:30 p.m., with the formal inductions commencing at 6:30 p.m. in the Halloran Theater. Tickets, which include the ceremony and reception admission, are $75 each and will be available starting on Tuesday, January 7, as will Blues Music Awards tickets.

Coinciding with the Induction Ceremony, the Blues Hall of Fame Museum will showcase a number of special items representing each of the Hall’s new inductees. These artifacts will be on display for public viewing beginning the week of the BHOF inductions and will remain enshrined in the museum throughout the next 12 months. The Blues Hall of Fame Museum, built through the ardent support and generosity of blues fans, embodies all four elements of the Blues Foundation’s mission: preserving blues heritage, celebrating blues recording and performance, expanding awareness of the blues genre, and ensuring the future of the music.

Museum visitors are able to explore permanent and traveling exhibits as well as individualized galleries that showcase an unmatched selection of album covers, photographs, historic awards, unique art, musical instruments, costumes, and other one-of-a-kind memorabilia. Interactive displays allow guests to hear the music, watch videos, and read the stories about each of the Blues Hall of Fame’s over 400 inductees.

The museum (421 S. Main St.) is open 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Mondays-Saturdays and 1–5 p.m. on Sundays. Admission is $10 for adults and $8 for students with ID; free for children 12 and younger and for Blues Foundation members. Membership is available for as a little as $25 per person.

ABOUT THE INDUCTEES

Performers

Eddie Boyd was born on a Mississippi plantation and, after working in cotton fields, took the Highway 61 route north, settling finally in Chicago in the early ’40s. His first hit, “Five Long Years,” wound up on Chess Records, which also released Boyd’s two other major chart hits: “24 Hours” and “Third Degrees.” Boyd, who also recorded for Bea & Baby, created powerful music that reflected the injustices and mistreatments he experienced and witnessed. Upset over his battles with record business practices and American racism in general, the proud, outspoken Boyd relocated to Europe in the mid-’60s after receiving a welcoming reception while on the influential 1965 American Folk Blues Festival tour. Eventually settling in Helsinki, Finland, the talented piano-man enjoyed a successful career overseas — even recording with Peter Green and Fleetwood Mac — until his death on July 13, 1994.

Victoria Spivey grew up in a rich musical environment: her father and brothers had a string band and two of her sisters became blues recording artists. At 20, she left her Houston, Texas home for St. Louis to pursue a singing career like her longtime friend, the popular singer (and Blues Hall of Famer) Sippie Wallace, had done. Spivey’s first single, in 1926, the risqué “Blues Is My Business,” was a huge hit, as was her 1927 recording of “T.B. Blues,” which epitomized her stark, moaning blues style. Her motto indeed was “Blues Is My Business,” and she demonstrated this throughout her life, from suing her publisher for royalties in 1928 to starting Spivey Records in the early 1960s. Her varied career also found “Queen Vee” as successful songwriter, bandleader, manager, church organist, jazz vocalist, and comedian, and she starred in the landmark all-black 1929 film, Hallelujah!. She also served as an inspiration for a young Bob Dylan, who played on a 1962 Spivey recording session and later included a photo of himself with Spivey on the back cover of his New Morning album.

Billy Branch was hailed as a leader of “the New Generation of Chicago Blues” when he emerged on the city’s music scene in the mid-’70s while still just in his mid-20s. The harmonica ace became known as a member of the Sons of Blues band (where ironically he was the only one who wasn’t a son of a blues musician) and for his many years playing with Willie Dixon. Always aware of the importance of blues’ past, present and future, the Chicago native began teaching in the Illinois Arts Council’s Blues in the Schools program in 1978, and has continued to conduct hundreds of blues classes around the globe ever since. Branch has been honored twice with the Keeping the Blues Alive Award in Education. Chicago’s most sought-after session harmonica player, Branch also has recorded albums for labels like Alligator, Blind Pig, and Verve. His music-making has earned him accolades too: he has shared top billing on three Blues Music Award-winning albums, including Harp Attack!, a 1990 collaboration with James Cotton, Junior Wells, and Carey Bell that spotlighted Branch as “The New Kid on the Block.”

Bettye LaVette’s musical journey has taken many ups and downs. Born Betty Jo Haskins, the Michigan native used the name Betty LaVett (which later evolved to Bettye LaVette) when she recorded her first single “My Man — He’s a Lovin’ Man” as a teenager for Atlantic Records in 1962. While that song was a top ten hit, her subsequent singles didn’t reach those chart heights, although her 1965 tune “Let Me Down Easy” is regarded as a soul classic. Stints on Atlantic/Atco, Epic and Motown didn’t work out, and her biggest success came performing in the Broadway smash musical Bubbling Brown Sugar for several years. LaVette’s European popularity (where her long-shelved Atlantic/Atco album was eventually released) eventually brought stateside attention. Her “comeback” album, A Woman Like Me, netted her a Handy Award from the Blues Foundation in 2004, and she subsequently won best female artist Blues Music Awards in both the contemporary blues and soul blues categories. Her unique genre-blending albums for ANTI-, Cherry Red, and Verve garnered Grammy nominations in the fields of R&B, Americana, and blues. LaVette’s long-overdue rise in prominence has led to her performing at the Kennedy Center, Radio City Music Hall and President Obama’s 2009 Inauguration Celebration. Her highly praised autobiography, A Woman Like Me, brazenly recounts her years of struggles, catastrophes, and dashed hopes, while pulling no punches about herself or anyone else.

Syl Johnson was born into a musical family — his father and several brothers all played music. Although his family’s surname was Thompson, the Mississippi native took the name Johnson when he started recording in Chicago in 1959. His older brother Jimmy (who was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2016) also changed his name to Johnson. An in-demand guitarist, Syl worked with Jimmy Reed, James Cotton, Billy Boy Arnold, Elmore James, Junior Wells, and fellow 2020 Hall of Fame inductee Eddie Boyd. His own music, a robust combo of soul, blues, and funk, yielded late ’60s hits like “Come on Sock It to Me,” “Different Strokes” and “Dresses Too Short,” along with more serious, socially conscious songs such as “Is It Because I’m Black” and “Concrete Reservation.” He recorded his biggest success, “Take Me to the River,” for Willie Mitchell’s Hi Records in 1975. Many hip-hop stars started sampling Johnson’s ’60s work, especially “Different Strokes,” and the resulting income — some of it by litigation — provided Johnson a comfortable lifestyle. In 2001, Syl partnered with his brother Jimmy on the well-received album Two Johnsons Are Better Than One, and the Numero Group’s Grammy-nominated 2010 retrospective box-set brought him more attention. Still active in his 80s, Syl has seen his daughter Syleena continue the Johnson musical legacy as a Grammy-nominated R&B singer/songwriter.

George “Harmonica” Smith is a legendary harp player whose published biographies offer conflicting information regarding both his name and birthplace. Not only did he perform and record under several names (Little Walter Jr., Harmonica King, George Allen, Little George Smith, and Big Walter), but also, over the years, variously said his given name was Allan George Washington or George Washington. What is known about Smith is he had superior skills on harmonica. He was celebrated for his mastery of both the traditional 10-hole diatonic blues harp and the larger chromatic harmonica. Although he never had a hit record on his own, Smith was highly regarded by his fellow musicians. His first band was Otis Rush’s, and his first recording session was with Otis Spann in 1954. Smith also played sessions with Lowell Fulson, Sunnyland Slim, Big Mama Thornton, Big Joe Turner, and Jimmy Witherspoon, and did several stints in Muddy Waters’ band. The longtime Los Angeles resident also mentored a corps of young disciples in California, including William Clarke, Rod Piazza, and Doug MacLeod. A working musician until the end, Smith recorded his final album just a few months before his death on October 2, 1983.

Individual (Business, Academic, Media & Production):

Ralph Peer is universally recognized as the foremost champion of roots music during the early days of the American recording industry. He is well known for his role in country music (then called hillbilly music) and was the first person to record Jimmie Rodgers, the Carter Family, and many more. However, Peer was recording blues prior to (and during) his country ventures. In fact, he participated in Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” session in 1920, which is acknowledged as the catalyst for record companies to launch “race music” catalogs of African-American blues, jazz, and gospel music. In fact, he is among those credited with coining the now long-retired term “race music” — a phrase which initially symbolized pride within the African American community. For OKeh Records, or, later, Victor Records, Peer recorded the Memphis Jug Band, Tommy Johnson, Blind Willie McTell, Bukka White, Sleepy John Estes, Gus Cannon, Memphis Minnie, Alberta Hunter, Sippie Wallace, Victoria Spivey, and blues guitar pioneer Sylvester Weaver. While instrumental in devising the concept of blues, hillbilly, and other genres, Peer, ever the businessman, shifted his attention to pop music in later years because he knew it had greater monetary potential.

Classic of Blues Recording: Album

Howlin’ Wolf: The Chess Box (MCA/Chess box, 1991)

MCA released several outstanding compilations of classic blues and R&B sides drawn from the Chess Records catalog in The Chess Box series. The Howlin’ Wolf edition (Chess CH5-9332) follows the Muddy Waters set to be the second Chess Box to earn Blues Hall of Fame admission. Wolf’s sixth Hall of Fame-honored compilation kicks off with his seminal 1951 recording of “Moanin’ at Midnight” and proceeds chronologically through 1973. The collection is loaded with performances that time and again bristle with the raw power and primal force that only Wolf (Chester Burnett) possessed. Released on a five-LP vinyl set or as three cassettes or CDs, the 71 tracks feature some previously unreleased gems as well as some insightful, and entertaining, spoken snippets, including one about how angry he once was that he could not escape the nickname Howlin’ Wolf.

Classic of Blues Recording: Singles

“That’s All Right (Mama)” – Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup (RCA Victor, 1946)

Big Boy Crudup’s infectious down-home jump “That’s All Right” (often called “That’s All Right Mama”) was a historic record not only for Crudup but for Elvis Presley, who covered it on his first recording session for Sun Records in 1954. Crudup’s original, recorded on September 6, 1946 in Chicago, was released as a 78 rpm single in 1947 (RCA Victor 20-2205). The track later became one of the first blues 7-inch singles when RCA Victor introduced the 45 rpm record in 1949 (release number 50-0000). Not so coincidentally, the executive who signed Elvis to RCA, Steve Sholes, had also produced Crudup’s Chicago session.

“Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean” – Ruth Brown (Atlantic, 1952)

1953’s best-selling R&B record, “Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean” (Atlantic 986), racked up more than 400,000 sales, according to Billboard magazine. The third of five Ruth Brown’s No. 1 R&B hits, it also was her first to cross over into the pop charts. The writers credited for the song, Johnny Wallace and Herb Lance, reportedly told Brown’s producer, Herb Abramson, that the idea came from an Atlanta street singer (possibly Blind Willie McTell, who had recorded a Blind Lemon Jefferson song, “One Dime Blues,” that contains the line “Mama, don’t treat your daughter mean”). Brown initially opposed doing the song and Abramson attempted several different tempos for the tune during the December 9, 1952 session before finally arriving at the right approach — one that highlighted Brown’s spirited vocal delivery and the insistent rhythm of Mickey Baker’s guitar riffing and Connie Kay’s drumbeat. While frequently covered over the years, it is Brown’s rendition that ranks as the definitive version.

“Trouble in Mind” – Bertha “Chippie” Hill (OKeh, 1926)

The oft-recorded Richard M. Jones composition “Trouble in Mind” was first waxed in 1924 by Thelma La Vizzo; however, it was Bertha “Chippie” Hill’s classic recording — made in Chicago on February 23, 1926, (OKeh 8312) — that paved the way for the many versions that followed. Hill was accompanied on this session by Jones on piano and a 25-year-old Louis Armstrong, who plays the introductory stanza on cornet. One of the top blues singers during the 20s, Hill sings three verses of misery and despair, but the first verse, repeated again at the end, is one of the enduring anthems of the blues as hope for the future even in the darkest of times: “Trouble in mind, I’m blue, but I won’t be always, the sun gonna shine in my back door some day.”

“Future Blues” – Willie Brown (Paramount, 1930)

Willie Brown may be best known in blues lore as a sidekick to Delta blues icons Charley Patton, Son House, and Robert Johnson. Highly regarded as a top-notch guitarist, Brown could have achieved more fame if he had more opportunities to record on his own. “Future Blues” is one of the few sides he made as a singer. An exemplary Delta blues tune with some now-familiar verses, “Future Blues” might be called Pattonesque in its rhythm and rough vocal timbre. Just as Patton reworked blues from Ma Rainey and other singers, so did Brown; “Future Blues” opens with verses from Rainey’s “Last Minute Blues,” composed by Thomas A. Dorsey (a 2018 Blues Hall of Fame inductee). The song was recorded at Paramount’s Grafton, Wisconsin, studio in the summer of 1930. Brown traveled there with Patton and House and accompanied them on a few songs. While not a big seller, the record (originally Paramount 13090) received an extended life when it was rereleased on the Champion label, and then, under the pseudonym Billy Harper, on Paramount’s Broadway subsidiary. In more recent years Canned Heat, Rory Block, Rocky Hill, and Langhorne Slim have covered the song.

“3 O’Clock Blues” – B.B. King (RPM, 1951)

After none of his first seven records hit the national charts, B.B. King broke through with “3 O’Clock Blues” (RPM 339), which became a No. 1 R&B hit in 1952. It was King’s first record to amply capture his emerging brilliance in both singing and guitar playing. Previously, King had been recording for the Bihari brothers’ RPM label at Sam Phillips’ studio in Memphis; however, after the Biharis fell out with Phillips, they set up their portable equipment at the black YMCA in Memphis. Aided by the valued support of Ike Turner on piano, King churned out a potent reworking of this mournful blues tune, which had also been the first hit record for its songwriter, Lowell Fulson, who released it in 1948. “3 O’Clock Blues” marks the third straight year a B.B. King recording has entered the Hall of Fame: his album Blues Is King was inducted in 2018 and his 1954 track “Everyday I Have the Blues” was inducted in 2019.

Classic of Blues Literature

Earl Hooker, Blues Master, by Sebastian Danchin

(University Press of Mississippi, 2001)

French writer, producer, and translator Sebastian Danchin played guitar with blues bands in Chicago during the 1970s, but he arrived a few years too late to spend time with Earl Hooker, who had died of tuberculosis in 1970. Danchin, however, lived in musicians’ homes on Chicago’s South Side and, through the friendships he made, he was able to glean invaluable insights about the colorful Hooker — whether it was his awesome guitar skills, his incessant traveling or his penchant for pilfering equipment. Utilizing this treasure trove of material, Danchin, who also has written books on B.B. King, Aretha Franklin and Elvis Presley, was able to compose an engrossing story about this Mississippi-born virtuoso who became a Blue Hall of Fame member in 2013. Although not widely known to the public, Hooker was championed by countless fellow musicians, including B.B. King. A cousin of the more famous John Lee Hooker, Earl was, in Danchin’s words, the “epitome of the modern itinerant bluesman.” His critically hailed biography is incisive, first-rate and to the point, just as Earl Hooker’s artistry was.