The Reverend Shawn Amos, singer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist, has a new band – The Brotherhood – a new album coming out next April, and a fervent desire to pay homage to traditional blues while also moving the music forward. Rev. Amos continues to hone his blues chops after a career behind the scenes as producer and A&R for the likes of Solomon Burke and Quincy Jones. The good Reverend told American Blues

Scene about all of this and much more during a recent chat.

You can catch Rev. Amos and The Brotherhood during their inaugural appearance at the 11th Annual 30A Songwriters Festival in South Walton, Florida, in January. Watch their touring schedule to see if one of the gigs they’ll be adding in the area will be at a venue near you.

If you are not familiar with Rev. Amos’s compelling backstory of growing up in Los Angeles, you can catch up by reading his four-part autobiography in the Huffington Post, starting here.

Stacy Jeffress for American Blues Scene:

You just got back from Spain. Weren’t you in Sweden also?

Rev. Shawn Amos:

Yeah, we did a couple weeks in Sweden and did nine days over in Spain. It was fun. Europe has a deep appreciation for blues. I mean it’s changing in the U.S., but over in Europe it’s part of what they live, drink, eat, and breathe on a daily basis.

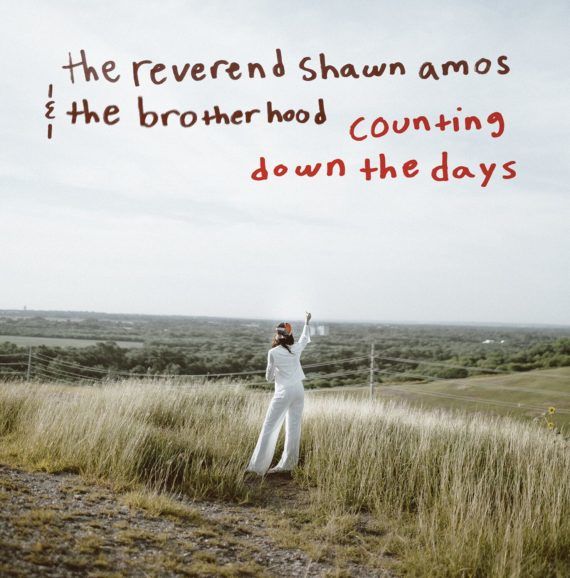

You have the new song and video out for “Counting Down the Days.”

We have an album coming out next year, but we released our first single about three weeks ago, a song called “Counting Down the Days.” We put out a lyric video.

So why are you so mad at Frisco, Texas? What happened?

[laughing]

Why is that lady flipping off what must be Frisco, Texas?

[still laughing] Why am I so mad at Frisco, Texas? No, I’m not mad at Frisco, Texas, at all. Frisco is serving as a proxy for any place somebody wants to get out of. In my mind, that song’s a little bit like a Bonnie and Clyde song. That woman on the single cover giving the finger to the city below is a modern-day Bonnie.

Did you move to Texas like in 2018 or 2017?

I moved in 2018. I went through a divorce and moved to Texas to be closer to my kids. Certainly a big move, and I’m still sort of assessing and dealing with it, and I have a bit of a love/hate thing, and an even bigger fascination with Texas. It’s sort of explored on the new album, not necessarily in overt terms. Before I moved here, it was easiest for a lot of people to generalize and stereotype about it and jump to certain conclusions about it. Some of those prove out to be true, but the place is more complex and diverse and full of ironies than one might think being from the outside of it. That sort of interests me.

You know Beto O’Rourke almost beat Ted Cruz.

When I first moved here, I went to some Beto volunteer groups. I thought it’d be a good way to (a) meet some like-minded people, and (b) give me some insight into Texas that went against my stereotypical notion of Texas. A lot of people that were there were sick of Texas being portrayed as a land of rednecks and gun-toting Trumpers. They see their state as being much more diverse than that and want to reclaim the narrative a little bit. America is a diverse place, period, end of story. We’re being lead to believe in some cases it’s not. America is diverse and always has been, it always will be, and it’s part of its strength. The challenge is how do we remember as a community that diversity is our strength. It’s a big part of what I write about.

One thing I’m really intrigued by is your look. You have a very stylized look and delivery. I love the hat and the shoes and the suits. Is the Reverend Shawn like your alter ego; is that who you really are even off stage? Or is this the persona you assume when you’re performing?

That’s a good question. When I first began this journey, it was certainly an alter ego I think I needed in order to help me find the heart of the music because I was still exploring the music as a performer. I was learning to sing the music, play it in a way that’s reverential but also as my own thing. I think having a persona, so to speak, was helpful for me in the form of method acting. And as I was doing those earlier albums, they’re all cover heavy. I hadn’t written my own blues material in any sort of large number. As time has gone on, I’ve begun to write more in the blues genre, it’s really emerged. The Reverend and Shawn are more the same person.

I watched an old episode of Biography on your dad, and there you were talking about him, and that was not Rev. Amos. That was some different guy.

Yeah, that’s an old piece, too. A lot of my favorite musicians were also essentially performance artists, David Bowie, David Byrne, even Prince to some degree. All of these people sort of assumed characters. Bruce Springsteen is a character of Bruce Springsteen by his own admission. I think it’s a big part of the tradition in pop music and rock and roll to be a bit of a character onstage. I don’t make any apologies for it. If it’s born from an authentic place, then go for it. For me, as I have begun to feel more confident about my own blues voice and the more willing to share some of myself, personally, the two personas end up colliding.

Are you really a reverend or is that just a name you use?

I am through the magic of the Internet, Universal Life Church. There’s a funny story about becoming a reverend. The name was given to me by a bunch of Italians when I first started playing blues over in Italy in 2012. After I finished each gig, they would start chanting, “Reverendo, Reverendo!” It was high praise if a bunch of Italian Catholics are going to call you “Reverend.” When I came back to the States, and I knew I was going to continue on this road, I thought I had to keep the name. The name helped separate me from my offstage life. I thought, if I’m going to use it, I’ve got to really be a reverend on some level. So, a Google search and Universal Life Church and $20 later, I’m a reverend, and I’ve got six wedding officiations to prove it.

About The Brotherhood – why is this configuration different from all the bands y’all have been in prior to this?

It’s the first time I’ve been in a band for a really long time. Everything else I’ve done as a blues player has been me and hired players who were playing what I asked them to play. It was a pretty scripted affair. It’s a big deal for me to share space. I had to admit to myself that, after years of being a bandleader and controlling every aspect of what happens on stage, I’d become a total control freak. As a result, I wasn’t growing. I felt myself beginning to stagnate. I realized that the only way out of that was to share space and be collaborative. Just the act of asking three other people to be equals in something and all contribute musically and to give up my final vote, so to speak, is a really big deal for me.

For them, they’ve been hired guns on a lot of projects. Brady Blade (drums) and Chris Thomas (bass) have played with everybody. Their life has been, they fly to a gig, they play it, and they have no emotional investments in these projects because they’re going to be gone in a few days or a few months. With The Brotherhood, we’ve all got skin in the game; the pride of ownership.

It’s the first time for me in a long time that, when we’re on stage, I have no idea what’s going to happen. I know it’s going to be great, it’s going to be transcendent, but I can’t tell you how it’s going to unfold. I know it will be phenomenal ‘cause I’m in good hands. It’s making me a better player, a better singer and writer. As a result, I feel that we’re moving the music forward a little bit versus being purely a nostalgia play.

How did you get connected with your longtime guitar player, Chris “Doctor” Roberts?

We met through some old band members. When I first came back from Italy and began to play some early shows in and around Los Angeles, my bassist at the time told me about Dr. Roberts. The funny thing about him is he’s a Texan from Houston and went to a music school in Denton (the University of North Texas). At the time he’d all but given up playing professionally, and he’s a real big jazz head.

When we met, he knew virtually nothing about the blues. I thought of it as an asset at the time. So many modern blues guitar players come with a soloist mentality, a shredder mentality. Their gravitational center of blues is Jimi Hendrix forward. I wanted him to pretend there are no blues guitarists that exist after 1958. I gave him my Hubert Sumlin, Willie Dixon, Little Walter records. His entry point to the blues had nothing to do with guitar heroism. He’s got a certain language and idiosyncrasy about his playing that I find really refreshing that stands out amidst a sea of modern guitar players.

You do a lot of really cool cover songs – your own take on David Bowie’s “The Jean Genie” and Devo’s “Whip It.” You wouldn’t expect that.

I guess it’s part of my mission overall to remind people of the connection blues music has to nearly every other genre. It’s like that Willie Dixon quote, “Blues is the roots and everything else is the fruits.” So when I listen to music in general, particularly music from the 70s, 80s, 90s, I’m always looking for the blues underpinnings. They’re generally always there, sometimes they’re more obvious than in others. They’re covered up by production stuff. Particularly when we were shooting the Kitchen Table Blues video series (Whip It), we were really into finding these songs that most listeners would never consider a blues song, but if you strip everything else away from it, you realize “Oh my God!” it’s a blues song. That was a fun exercise.

In your NPR piece that aired January 17, 2016, you said that during your youth in Los Angeles, you knew hookers and dealers by name.

Yeah, on my street corner, that’s where I got my carpool. It was Hollywood in the 70s. It was a different time, a different place. Going to 7th, 8th, 9th grades, they’d greet me in the morning as they were getting dropped off from their night job, and they’d greet me when I was coming home as they were waiting to get picked up for their jobs. My father was an agent, so I spent a lot of time in night clubs, comedy clubs, and recording studios and sound stages. An apartment building I lived in early on had gay porn actors living in it. With all those gigs, whether it’s being a composer for a movie or a stand-up comic or a hooker, I just saw them all as these jobs that people do. I saw these people coming to work and going to work, and none of it was glamorous. Making music in a studio wasn’t glamorous, sitting in the Comedy Store at ten o’clock at night was not glamorous, being backstage in the green room waiting for my father’s clients to go on a talk show wasn’t glamorous. The only things that was glamorous was the stage show itself. It demystified for me and made it all seem like a job, me being hard to impress with the whole trappings and the business of it. I’m grateful for that, it’s what helps keep me pretty even keeled about stuff and not freaked out about much.

The Reverend Shawn Amos

*Feature image Semaj3