It was just past dawn on Monday morning, August 18th, 1969 and Jimi Hendrix was closing out the original Woodstock Music Festival. Vietnam veteran Fred Jack remembers it as clearly as he remembers what he did an hour ago.

“I was as wide awake as you’re gonna get with a couple of LSD tabs under my tongue and trying to find my motorcycle, yes! It was early in the morning, and I hadn’t slept all night long. A lot of bad acid and mescaline was going around, and they were telling us about the bad brown mescaline, and I took that shit. I trusted everyone. These were people running around totally nude with kids. That was the way you lived.”

It was Fred’s 21st birthday. Two months home from Vietnam, he was transported from hell to heaven at warp speed. “Nam was over and I was back in New York. This was life, friend. Hendrix came on that morning with ‘Star Spangled Banner’ and ‘Foxy Lady.’ Noel Redding was his drummer at the time, and he was so high, he passed out and went into some kind of attack. It has to do with his respiratory system. Never forget it. I wanted to get up there and play the drums. That’s how close I was.

“Hippies! What the f*** are hippies? Fresh out of the bush, buddy. I just couldn’t break away with the way people were thinking and living. So, I had somebody take me under their wing with the bike and what little shit I had. You know what these people looked like to me? They were from f***ing outer space.”

Fred was wearing jungle fatigues and combat boots. “If they’d (given me a lot of clothes) I would have put ’em on, man. I wanted to be where they were at. I’m not shittin’ ya. That was the best thing I had ever in my life.”

Fred had taken his 1950 Harley panhead out of the garage, put the $75 his dad had given him, slipped it in the pocket of his jungle fatigues and headed south. He had gotten to the fairgrounds on Thursday, parked the Harley under the stage and fallen asleep.

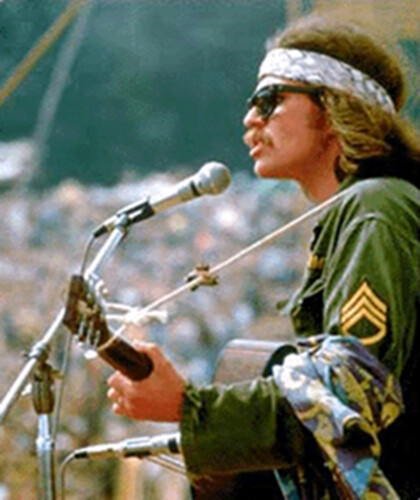

Country Joe McDonald had been in the Navy in Japan from 1959 to ’62. With his band Country Joe and The Fish, he sang the most anti-war song performed at Woodstock, “The Fish Cheer / I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die” with its chorus:

And it’s one, two, three, what are we fighting for?

Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn, next stop is Vietnam

And it’s five, six, seven, open up the pearly gates

Well there ain’t no time to wonder why

Whoopee! we’re all gonna die

That said, he told me in 1988: “I never dreamed that song would become so popular. Most people from the anti-war movement who are not vets think the song is putting down soldiers, but it’s not, really, and I never had that intention in mind when I did the song. I’m glad the song went where it did and seemed to be a morale booster to people working against the war and for people fighting in the war, too. I never thought the soldiers were to blame for what was happening in Vietnam. I never thought the soldiers were evil and bad.”

“I went to sleep and woke up to Richie Havens opening the festival doing ‘Freedom.’ I thought I’d died and went to heaven. (I thought) This is gonna work. It was performance after performance. It was him. If I’m not mistaken, Country Joe and his guys came on after, and I said, ‘What the f*** is he doing?’ It was awesome, bro. I had the most wonderful time. I will never ever erase that memory. I had conversations with Richie Havens. He (was a dude that) had some kind of commune, and I didn’t even know what a commune was. He was wild.

“I had my green jungle fatigues on my ass when I rode to Woodstock and my Vietnam boots.” Fred Jack was in the platoon featured in the film Full Metal Jacket. For 17 days his platoon fought their way through the ancient city of Hue. “We were losing anywhere from three to 15 or 20 of our troops in a platoon of 90, three platoons daily. This went on for 17 days…non-stop…it didn’t stop. It was hit after hit…door to door…building to building.”

Fred earned three purple hearts. “I got burned across the top of my body. You can see the discoloration from a rocket that was misdirected, and I caught the white phosphorous all over the top of my body. That was one. The shrapnel in my face was another one, and the gunshot wound was a single incident. I had my share of that shit, man, you know.”

Two months before he went to Woodstock he flew home from Nam. “They brought me back to Da Nang, they got me on a C-130, piled about as high as this garage with dead bodies in aluminum caskets per se, boxes with straps around them that high of dead people.

“I remember going through the airport in Chicago, and people throwing water balloons at us filled with piss and you name it, man. It was goin’ on and defecation and screamin’, ‘You f***in’ baby killers…scum bags…’ and, oh my God, that was the normal behavior of the American war protester, hippie-type person back then. They hated us, they hated us.”

But not at Woodstock.

If you were there, you were family even if you wore combat fatigues. “There was a lot of LSD going around, a lot of mescaline going around during that weekend. I thought I was on a huge ship, for some reason, I don’t know why, because of the rain and what have ya. I had this imagination that I was on this huge ship, and it was gonna float away and never come back to the country again. I don’t know what I was on, man, but it was a good time. It was the most significant time of my entire life as a human being. I’ll never, ever forget the good time that I had there.

“I was there, and that’s where I wanted to be. I went through the three days of rain and experienced that and all this beautiful shit that was going on with the mud. Donnie, I only wish to God you could have been there so you could understand my sights in my head. I can’t erase that, bro. You know?”

The memories flash through his mind, an emotional light show:

Johnny Winter: “It was brief. He wasn’t set up properly for some reason. I don’t know what happened, but it wasn’t a full show. I think he had electrical problems if I remember right.”

Crosby, Stills & Nash: “They came on at night. They had light shows and oh, man, the dude said, ‘This is the first time we ever played in front of people, man’.”

Ten Years After: “I watched them on stage early in the morning. They came up on, on Sunday morning and did a show.”

Janis Joplin: “I watched Janis Joplin who was very brief and quick, but I seen Hendrix and her both… they’re both gone.”

Fifty-one years later, Fred Jack is on the road calling from Florida. “I’m fine, bud. I’ve been on the highway since January. I’ve been to Tucson, Frisco, San Diego, Idaho, back down the San Bernardino Mountain range into Tucson and Yuma and then from Yuma back into Florida. What a ride!”

He’s driving a 1999 23-ft. Chevy motor home with one of four speakers working. “I got four speakers throughout this whole bomb. The back is dead. I got one speaker in the right front door that I listen to every day. I listen to rock and roll, stuff that went down back in them days. You know what, bro? It’s like I got a symphony orchestra in front of me. Just knowing what I know about these artists and the times this stuff went down. I got to live my life in that time and era. It’s such a wonderful feeling, bro. Let me tell ya.”

He just had to leave Albany. “The pandemic was running rampant. It scared the shit out of me. I was isolated, but I didn’t like my situation with the VA there. It was terrible. I was scared shitless because a lot of the patients were coming right through that system, you know? Yeah, I didn’t like it, Don. So, I pulled up my reins and said sayonara.”

Vietnam to this journalist was like an inoculation. The disease is in me permanently, but it kills some of the fear of the coronavirus and makes me, Fred and other veterans better able to handle smell of death around us.

“Absolutely! Same mindset. It’s just another day in paradise, buddy,” says Fred. “That’s the way I’m looking at it. I don’t give a f*** about who gets where or what and when and how many cases they get confirmed and who’s dying. It’s no different than the daily routine in the bush.”

This journalist has been very lucky, but it’s been a rough 52 years for Fred. “I’ve been in so many relationships that my PTSD totally destroyed of course, but you’re doing pretty good, man. I’m glad to hear from you. I really am. I’m so happy I got in touch with you. I really am.

“There’s nothing the VA can do. They got no magic pill. The got no magic doctor. There’s nothing available. It’s you’re on your own, asshole. And it’s been that way since 1969, and it will stay that way. I will be honored that you know the deal, Donnie. I have no problem speaking to you about any of my shit in any form that it went down. I don’t worry about that because I know you will protect me. As you protect me, you will protect my family.

“I’m 70, and I’m still kicking shit over like I always did. Nothing’s changed but the weather. I have the same mindset I had when I was in the Marine Corps, and it’ll never change, and I thank God for that, bro!

“I’m sharp as an arrow, bro. I’ll tell ya. Anything that comes my way it’s gotta fly in my direction to where it’s acceptable. You know what I mean? If there’s a situation that rocks my world a little bit, ok, well, that’s cool, but if it gets too close, my tripod is out, and I’m locked and loaded.

“I’ve been trying to get financed for something that’s up to date. This thing’s a wonder wagon, dude. I’m tellin’ ya. It’s like being in the bush. It’s a struggle. Things may change any time soon, but I’ll stay out of the monsoon a little bit more and fight this shit. I’ve got pretty much minimal bills.”

There is a bond among veterans that’s like no other. “Yes, sir! And only you would be able to get that. I’ll tell you that. Nobody else! You and only you because you care about people like me and your concerns about the situation we all get ourselves into, one way or the other. It’s real, man. And you know what? Bring it on, man. Bring it on. My magazine is loaded. I don’t give a f***.”

No one can take the memory of Jimi Hendrix playing “The Star Spangled Banner” into the dawn of a new reality in Fred’s head in 1969. The music is the medicine, the life line that makes the horror go away.