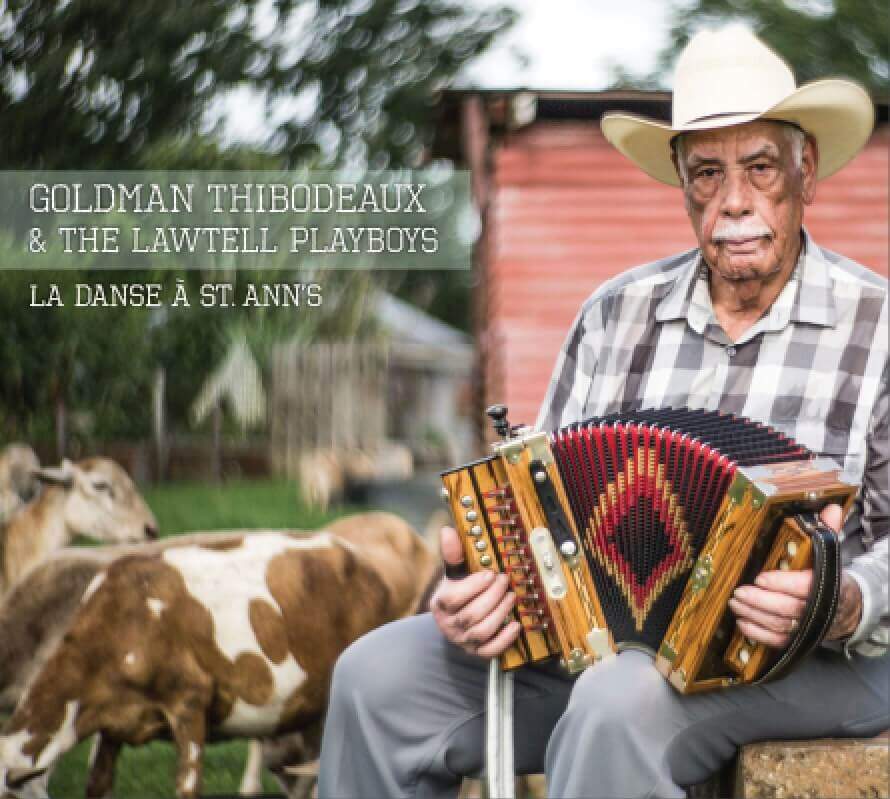

There’s soul music that refers to soul, the musical genre, as exemplified by Al Green, and there’s soul music that refers to its spiritual origins. Goldman Thibodeaux and the Lawtell Playboys‘ La Danse à St. Ann’s is the latter, a zydeco master at his peak leading his band through a live set recorded at the 2019 Thibodeaux family reunion. You don’t need to know anything about zydeco to understand the quality of this performance. You’ll know immediately as you find your mood improving, your body swaying to the wildly controlled grooves, Thibodeaux’s expert accordion work propelling you into a state of wonder and delight.

And to be clear, I don’t know anything about zydeco, other than that I enjoy it. I don’t speak French creole, the language of the album. I don’t know the names of the different kinds of zydeco styles. And yet I knew, within seconds of playing this, and of hearing Thibodeaux’s accordion and voice, more bark than lilt, both seemingly directing the drums and fiddles that swarm protectively around him, that I didn’t want it to ever end.

Often, when you talk about a person’s energy, it’s a proxy for their age. But given Thibodeaux is 87, you almost have to talk about both. His songs are fast but not frenetic. He pushes tempos but he’s mindful that songs need to breathe. And by laying back just a bit, he allows the rest of his band to speed things up. His playing isn’t pristine, which just makes the accordion feel that much more present and is a reminder that this is a live show. And that voice. I have no idea what he’s saying, but it’s pure charm and smirk with a bluesy undercurrent. In a different universe, Thibodeaux might have been a bluesman, but in ours, we get to hear that muscular growl over those flexing tunes. His voice betrays his age, in that there’s a weariness and experience to it, but there’s nothing tired or old about it.

Thibodeaux first started performing at 14, hooking up with the Lawtell Playboys in his 30s, learning to play accordion in his 50s (following a heart attack), eventually taking over the band. The St. Ann’s in the album title refers to Thibodeaux’s own church: the site of this gig, as well as his very his first one; the church whose priest helped arrange for the adoption of Thibodeaux’s two sons; and also where the devout Thibodeaux prays. All of it adds to the warmth of the album as, right before the second track starts, he announces that the food is ready, encouraging everyone to go get some, like you’re over at his house for dinner. The album ends with someone trying to organize a family photo taken with a drone, the only thing anchoring this timeless set in the present.

The album flows perfectly because Thibodeaux keeps an eye on the dance floor, figuring out which kind of song people need to hear next. So a slower trundle of a tune, like “Lucille,” with Thibodeaux and the fiddles doing a call-and-response, segues into “Jolie catin,” a faster number with just a hint of a punk rock beat. And so it all flows. The tracks certainly work alone but the power of La Danse à St. Ann’s is how well the tunes melt into and out of each other. I doubt I’ll ever be able to finagle an invitation to a Thibodeaux family reunion (although if any Thibodeauxs

are reading this, please feel free to invite me), so I’m grateful for this document from a soulful master.