Editor’s Note: Rearview Mirror is a regular feature provided by Don Wilcock as he works on his memoirs.

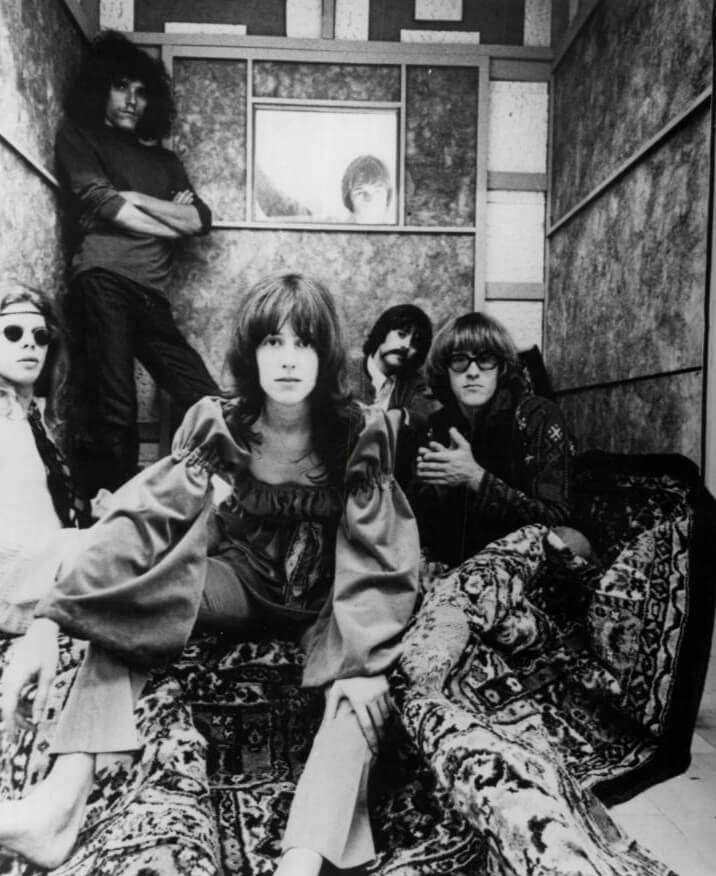

Grace Slick may have been on the frontlines of feminism in 1965 when her band Jefferson Airplane topped the charts with “Somebody to Love” and “White Rabbit,” songs that helped write the New Testament for the psychedelic movement. But by the time I interviewed her in 1989, she was an old before-her-time 49. My cover story in the Troy Record’s Steppin’ Out entertainment tab in New York CapitalRegion previewing the band’s reunion concert at Saratoga Performing Arts Center had a headline written by Arts Editor Doug DeLisle that screamed: “Slick: ’60s Acid Queen mellows into the 1990s.”

“I like being on stage,” she admitted, “but I would rather have an appearance that was not intimidating to me to have to wear certain clothes and do certain things with my face because I am almost 50 in order to just look normal. And I think if I was younger, I’d be freer physically.

“I’m not crippled or anything. I never did leap off amplifiers. So, that’s not one of my things. But I think anybody over 35 in a sleeveless dress is making a mistake unless you work out eight hours a day. If you work out eight hours a day you wouldn’t be on stage because you wouldn’t have time to practice the music. I don’t know where Jane Fonda gets the energy, but I haven’t seen her under arms either.

“The music can be written by a person who is 105 if it’s any good, but I don’t want to see anybody who is 105 wearing tight leather pants and singing about “I wanna take you up to my room tonight. Here’s my hotel key.”

Her view of herself was startling and out of character even in 1989 considering the import the Jefferson Airplane had in 1965. The idea that they were functioning at a time that offered a virtual petri dish of cultural fermentation helped create a big bang creatively. The timing in the mid-60s was perfect for such creative experimentation. And Grace Slick was one outrageous flag waver for what passed as feminism in the ’60s.

The success of this new youth movement was precipitated by four things: the above mentioned folk movement that introduced the American songbook legacy to young academics, the unprecedented success of the British Invasion, the evolution of expansive FM playlists, and the desire by young people to cut away from the postwar conventions that led us into a war that no one of that generation believed in.

Something had soured Grace in the quarter century since “White Rabbit.” Maybe it was the fact that despite their early success they hadn’t saved a lot of money. But none of those things has stopped the living members of the Grateful Dead and Jorma Kaukonen of Hot Tuna from being even more vibrant today than they were in 1965. But the San Francisco movement ran on a diet of drugs. Some grew out of the habit. Some died, and others just got old faster than average. Grace Slick was in this last group.

“The drugs that are taken now are to avoid reality. You wouldn’t want to go around and take a lot of acid now because that intensifies what’s going on. So, if you’re miserable, you don’t want to take any acid. It’s a totally different drug and a totally different reason for taking drugs. Alcohol is a get-awayer.

“A lot of people are what is called recovering alcoholics, and they’re in programs. They’ll say ‘Oh, my life is so wonderful now. It was miserable.’ Maybe it was miserable. My life I don’t think was particularly miserable. I enjoyed the shit out of it. There comes a point where the drugs and alcohol stop working for you, but the problem is we’re not handed a little card when we’re born saying your cutoff point is 16 years old. Your cutoff point on the other hand is 36. And you, Fred, your cutoff point is 78. My father stopped drinking when he was 79. He had a year and a half of sobriety. He died when he was 81, but he had a year and a half. My daughter, on the other and, stopped when she was 15. So, you never know.”

Grace married Jefferson Airplane’s founder and lead guitarist Paul Kantner. She told me in the mid-80s that she’d gone into their office one day and found he’d punched the eyes out of everyone in the Airplane poster. They divorced, and he died in 2016.

Now retired, she licensed the Starship song “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now” to Chick-fil-A in 2017 to use in a TV commercial, even though she disagrees with their conservative Christian views. She gave all of the proceeds of that deal to Lambda Legal, an organization that works to advance the civil rights of LGBTQ people and everyone living with HIV.

Early on Grace Slick may have been a model for feminist reformers like Gloria Steinem, but she had already stepped back from the spotlight by 1989.