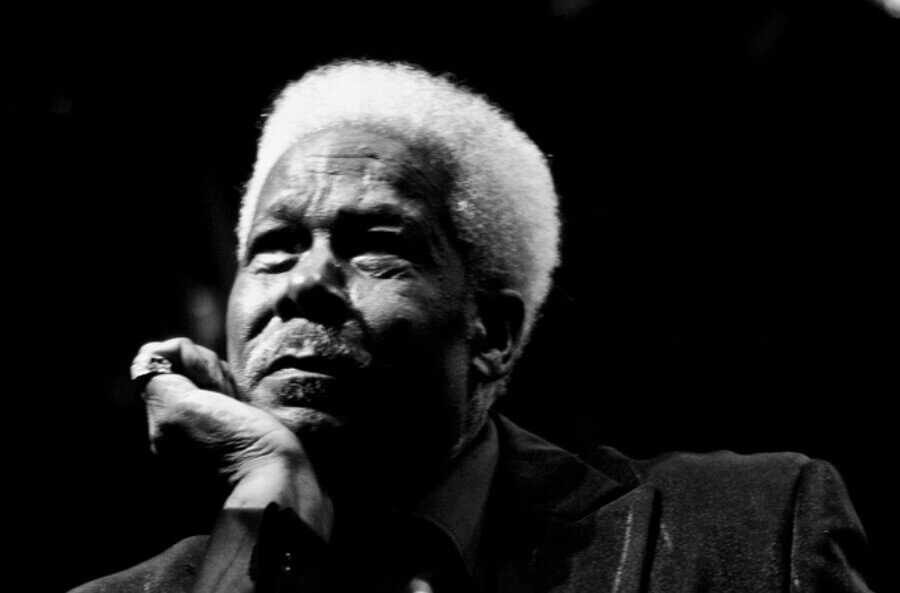

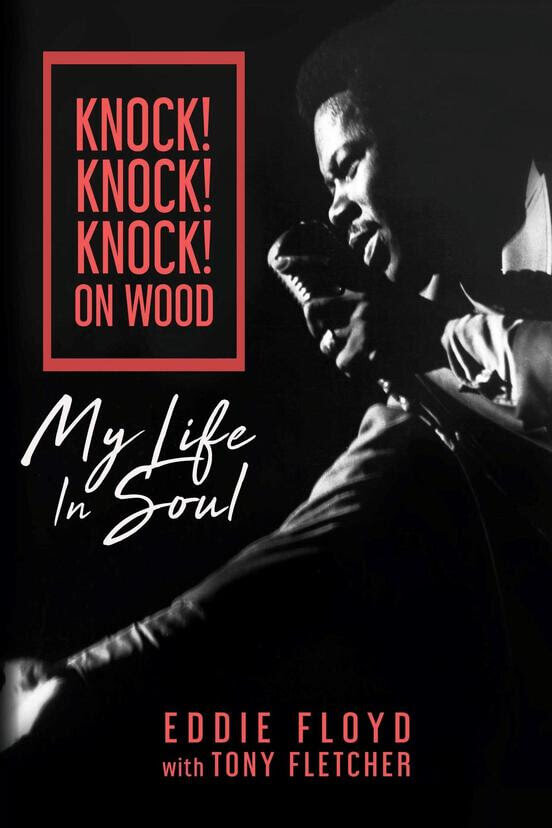

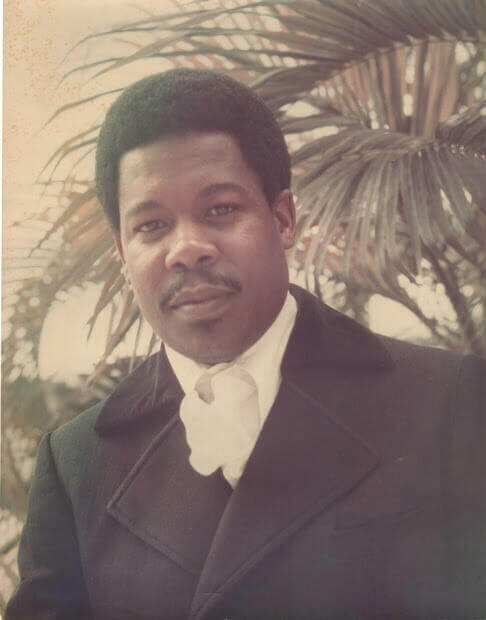

Known for the soul classics “Knock on Wood,” “634-5789,” “Raise Your Hand,” “Big Bird,” and “I’ve Never Found a Girl (To Love Me Like You Do),” among others, Eddie Floyd has been a soul legend for more than 60 years. His professional singing career began in Detroit in the 1950s, when he co-founded the Falcons, considered by many the first soul group. A solo artist and songwriter for Memphis’s famed Stax Records from 1966 until 1975, Floyd has subsequently been the singer for the Blues Brothers Band and for Bill Wyman’s Rhythm Kings, while continuing to perform and record solo.

In Knock! Knock! Knock! On Wood, Floyd recounts how a three-year stint in an Alabama reform school shaped his young life; recalls the early years of R&B in Detroit alongside future Motown and Stax legends; discusses the songwriting sessions with Steve Cropper and Booker T. Jones that produced his biggest hits; addresses his complicated lifelong relationship with the often-unpredictable Wilson Pickett; shares his memories of friend Otis Redding; reveals his unlikely involvement in the rise of Southern rock darlings Lynyrd Skynyrd; and offers an insider perspective on the tragic downfall of Stax Records.

With input from Bruce Springsteen, Bill Wyman, Paul Young, William Bell, Steve Cropper, and others, Knock! Knock! Knock! On Wood captures Eddie’s tireless work ethic and warm personality for an engrossing first-hand account of one of the last true soul survivors.

Eddie Floyd Arrives in D.C…

I figured on starting another label, doing it right this time. That’s when I got talking to Chester Simmons. He said, ‘You need to meet Eddie Floyd. He’s a great singer, a great writer, and a great person. You’ll work well with Eddie. You’ll like Eddie. And I’ll work with you also.’”

And that’s what we did. We set up our label and called it Safice: like Stax, it was made up of our last names’ initials, though I’ll leave you to figure out the order of them! A lot of people don’t know much about Safice; it’s one of those labels got lost in the shuffle of time, but we recorded a lot of music in just a year or so—from about the middle of ’64 to the middle of ’65. I guess Al Bell must have seen something in me.

“Eddie didn’t know this,” Al recalls. “But after a couple of meetings with Eddie, based on what Chester had said about the writing, I started listening and talking to him, and said, ‘Holy . . . he is a writer.’ I wasn’t and am not a writer, but I knew how writers wrote. I even developed a formula, from just listening to and writing down the lyrics to the songs. And I listened to Eddie Floyd and said, ‘Yeah, he’s it.’ As a matter of fact, Eddie Floyd was to me as a writer what Smokey Robinson was to Berry Gordy.”

We kicked off the Safice label with a local D.C. group called the Mystics, and a doo-wop song I wrote for them with our pianist Al Haskins. Al and Chester got it sold to Ewart Abner, who’d just left Vee-Jay to start a label called Constellation. Al remembers that it was Abner who then told him—but politely— to look elsewhere next time. “You need to go to Atlantic and deal with Jerry Wexler,” Abner told Bell, “because I can’t market that music as effectively.” Jerry Wexler, just like my uncle, knew the value of having a disc jockey like Al Bell on his team and agreed to distribute Safice straight away. That meant my first single on Safice, just like my last single on Lu Pine, had Atlantic behind it.

Both sides were solo compositions. “Never Get Enough of Your Love” was the first song of mine that tipped towards the sound of Otis and William Bell, that Southern soul ballad feel as opposed to the doo-wop I’d grown up with in Detroit. “Baby, Bye” the other side, was much more of an R&B thing, even had a bit of a Motown feel to it, so Detroit must have been sticking with me even as I traveled. Still, I opened it with a line about my new home—“You’ve been running around, all over D.C. town”—and it went on from there. A good song should tell a story, and a good story needs some detail. A location always helps.

What I liked about that single was not only that I wrote both sides on my own and that I was proud of them but that my voice came through loud and clear; the three of us were obviously working well together. And Al Bell was benefiting from his closer ties to Atlantic. Jim Medlin, the label’s head of national promotion, introduced Al to Milt Gabler, who ran A&R at Decca. Milt was well known, a sophisticated jazz man, and he brought us the singer Grover Mitchell.

I loved Grover. He was from Georgia, had already bounced round a whole load of labels without a whole load of success. But the man had a voice that would give Wilson Pickett a run for his money, and you can hear it on the song I wrote for him called “Midnight Tears.” (And in case you’re wondering about the title, this is before Pickett came up with “In the Midnight Hour.”) For the flip side of the next single we did for Grover, he sung a ballad that I wrote with Chester and Al, called “I Will Always Have Faith in You.” Nobody really heard it at the time, but it’s a song with a deep gospel feel to it that would come back for me many times over. Our songwriting was starting to take shape.

For Grover’s third single on Decca, Milt Gabler came to Washington and got the Howard Theater Orchestra to play behind us on my composition “Take Your Time and Love Me,” which would then get a very different, very Motown arrangement when re-recorded the next year on Josie. But then I got put in with the orchestra too. My first solo single on Safice having made a little bit of noise, Jerry Wexler suggested I put my next 45 out straight through Atlantic. Thing is, Atlantic was into big arrangements and productions; just when we’re getting things together in our own musical field, in what’s now being commonly called “soul” music, I’m back in that Don Costa world. I gave it my best, but on that single—“Hush Hush” and the ballad “Drive On”—my voice is buried by the orchestra. You can’t win them all.

Still, by this point the three of us—Al, Chester, and me— figured that we just about knew what we were doing, which is why, when Al Bell told me that Carla Thomas was attending college at Howard University—right in the heart of the D.C. music scene, close to the theater and the night clubs and my apartment—I pushed for him to arrange a meeting. I knew that opportunities like this didn’t come along often.

Fortunately, Carla felt the vibes, and they were good. “It must have been some kind of karma,” she recalls. “By Eddie coming to Washington, by me being at Howard University. There was just something about me and Washington, and Eddie and Washington.”

In short, when Al called her up, Carla expressed interest in working together. It might have been the very next day we came up with “Stop! Look What You’re Doin’.” And maybe even that same day, “Comfort Me.” Both were ballads, in the 6/8 time signature, smooth rhythm & blues tailored especially for Carla’s voice. I wrote both of them with Al; I was generally the one who came up with the melody, and Al saw his strength as being to help tell the story.

“It was, Cause in the first verse, the Effect in the second verse, then the bridge, and then the Solution,” says Al. “So you create a Cause, the Effect of the cause, and then a Solution. I felt like that and I wrote like that. In writing with Eddie, once we set up the Cause, my mind went straight to Solution. So I would contribute what I had heard in other songs, how people approached Cause, Effect, and Solution, that in influenced my thinking. And it owed so well with the two of us . . .”

Now, here’s how I go about writing a song. Most times it starts with a title. Get a title in. Then, whatever the title feels like dictates the speed of the song: slow, fast, a ballad. Certain things you see or say, for example, you just know it’s meant to be a ballad. Then you try to come up with a concept of lyrics. And then that melody will come to you—if you’re a songwriter, that is. If you know how to do that. If you just wrote some lyrics and didn’t know how to sing nothing, it wouldn’t mean nothing. But I know how to project, looking at those lyrics and how it becomes a melody, and I feel a melody in it, and make it be a melody just in the words that I see: So a simple phrase like “Come on and comfort me . . .” It’s almost like I’m singing when I’m seeing the words. I’ll sing it to you instead of talking to you.

Next, decide on what key you’re going to sing something in. A lot people used to play all their songs in one key. I would sing a song in almost every key, and it might not even sound like me, because if you sing one register, your voice sounds one way, and if you sing another register, it’s going to sound a little different. I could hear another artist sing, and they would sound the very same on every record that he sung; that’s because they were singing in one key. I just didn’t find that as being exciting.

With our songs in the bag, Carla said she’d come down to Al’s radio studio after her classes. At seven o’clock we’re at the studio in D.C. with our guitarist Al McCleod, we teach the song to Carla, and she sings it. She was—and is—a natural, and a good soul singer doesn’t need more than a couple of takes. So now we got a demo of the songs. All we have to do is convince Stax to record one of them.

Carla might have been able to call that one on her own, but it certainly didn’t harm to have Al on the team. “Jim Stewart would call me in D.C., ask me about the new Stax music, and ask me what I thought of it,” he recalls. “He wouldn’t ask me to play it on the radio because he was too diplomatic! But, of course, I was playing it anyway. So I had an opportunity to talk to him about this demo for Carla Thomas, and we sent it down to him, and almost immediately, he calls me back and says that they’d like to record ‘Stop! Look What You’re Doin’’ at Stax. I said, ‘Well, she’s not going to fully understand the songs unless Eddie explains and sings it to her, so he needs to be there too.’”

Down we all go to Memphis. It was the summer of ’65, and although I can’t remember exactly who was on that first session I witnessed, that’s partly because everyone seemed to be there. Even those who weren’t on a session would be in the building, likely in the studio as well, offering ideas, helping out where needed.

A few weeks later, “Stop! Look What You’re Doin’” comes out on Stax, and immediately I’m hearing it on the radio everywhere. I’ve had hits before, of course, with the Falcons, but not on a song I’ve written, and not for someone I already consider to be a star. It makes it all the way to the Top 30.

For me, this is the moment it all comes together. Having Carla take a song of mine into the charts is like opening a door from one world into another, this one full of artistic activity at a higher level. Al gets talking with Jerry Wexler some more, and next I know, we’re writing for the great Solomon Burke, which means soon we’ll have another hit when he sings our “Someone Is Watching” in that comforting preacher style of his. Carla follows up by recording “Comfort Me,” which is another great honor. I wasn’t there for this session, though; I was out performing on my own, and it was only when Carla and I were on a radio interview together in 2017 that I heard who actually sang back-up: Gladys Knight & The Pips, the same group I’d been so impressed by in Chattanooga back in 1961! They’re still not on Motown yet, but at least we’re all moving forward together. Then Al gets talking with Jim Stewart again, and next I know, we’re all headed back to Stax—this time to record our own singles on Safice. (Jim was letting a lot of outside artists use the building at that time, especially those that had a connection to Atlantic.) We’ve got this guy Roy Arlington who we figure to be our potential star solo singer, and we’ve written a ballad for him called “Everybody Makes a Mistake Sometimes.” It’s a classic guy-playing-the-field-and-losing-his-girl number, and it would become well known soon enough.

Down at Stax, we get to cut a single on me as well, a song called “Make Up Your Mind” that I wrote on my own. It was one hell of an experience, recording at Stax that first time. We brought Al McLeod with us—Steve Cropper stayed up in the booth as producer—but otherwise we were working with the Stax house band. In D.C. we would have different musicians that played with us, might not even know half of them. But at Stax, that was a family. It was the Mar-Keys! It was the M.G.’s! And they’re already proven, because they’re already recorded behind other people. So, when you get down there and hear that, how can you miss? You’re with the real guys.

These guys were so committed. Every morning everyone would come to the studio, and if there were any songs to be played, they would all join in and play on the songs. Not necessarily working because it was a regular job, but just showing up because they could possibly make some music. And they had the time available to come in and play. It was just family, the attitude of everybody. You had no tension in any kind of way. It was all about the music.

I’ve been asked the question millions of times, “How was it back then, them being white and you being black?” Well, don’t forget I put an integrated group together ten years earlier, when I formed the Falcons, so this is nothing new to me. But for another thing, there were maybe four white people in the studio, and all the rest were black. So it wasn’t too much different from anything else, it really wasn’t. It was Wayne Jackson, the trumpet player who always seemed happy to be in the studio. And then it was Donald “Duck” Dunn on bass and Steve Cropper on guitar. I sang, and it worked out just fine!

Just go back to everything we did: it speaks for itself. I loved to hear Steve Cropper play, and I definitely loved to hear Duck play bass. Listen to him on “Make Up Your Mind.” He’s up and down that Fender Precision like a hound dog in a rabbit hole. Duck was a very genuine person. I loved him with all my heart. He was the kind of guy who laughed a lot and said funny things all the time. Never seen him frown. There was just always a smile; that’s the way he was.

Everything at Stax was done live. Nobody stopped you just ’cause somebody coughed. We tried to be quiet when it was time to be quiet, and we sang when it was time to sing. We had the barriers and the separations and that, and a little corner where we used to sing. But it was a big room, and nobody had headphones. Cropper said he always measured his guitar playing to the beat, not by listening to Al Jackson but by looking at him: when Al’s wrist would come down on that snare, that’s when Steve would hit the guitar.

We came back up to D.C. with four solid tracks. Really good tracks. Did they hit? Well, both my single and Roy Arlington’s made some noise, especially in D.C., but not quite enough. Maybe if people knew they’d been recorded at Stax it would have made the difference; if they’d been on Stax then I’m sure it would. As for Atlantic, we had their distribution, but we didn’t have their promotion. What we had at Safice was Al Bell, and good at promotion that he was, he had a day job as a disc jockey. When all was said and done, ours was a tiny little label, and Al—well, he was always thinking big. And now, so were the people at Stax. They wanted to lure Al back to Memphis.

“I knew Al to be a good contributor of ideas,” says Steve Cropper. “Also, a good songwriter and so forth. But the reason we really needed Al Bell was because he knew everybody in the business. We needed to be able to get into people’s of faces and say, ‘Listen to this.’ I knew that if I played people a Stax record they’d go, ‘Man, I got to put that on the air!’ because it was just the right music at the time. But there were so many doors that were closed, unless we had somebody like an Al Bell to call a friend and say, ‘Hey, listen to this.’ Without that, you don’t have a chance.”

Al recalls it playing out as follows. “Jim calls and says, ‘Al, we’re about to go under, we’re $90,000 in the hole, and you know our music. Can you come down and take over the promotion?’ So I called Jim Medlin at Atlantic. He said, ‘Al, you know I know this business. I know you. Take that job and go do what you know how to do. That’s the only company around here that has the kind of bottom sound that’s in Stax Records.’

I said, ‘What do you mean, the bottom sound?’ He said, ‘I’m talking about the bass drum and the bass guitar, there’s no other bottom sound like that in this industry, and it’s going to be huge. And the way you know how to do things, you can go in and help turn this company around.’ So I asked Jim how much he’d pay me. He said, ‘I can give you $100 a week, and Jerry Wexler said he will give you $100 a week—and we can give it to you in cash.’ I said, ‘Do you know what I’m making in D.C.?’ I was making mid-high five figures in D.C. at that time, and they’re offering me $10,000 a year!”

But hey, I guess Al lowered his salary, because next I know, we’re closing up Safice. Chester Simmons gets himself a job doing promotion for Chess in Chicago, and Al’s telling me I’m going to be a permanent part of Stax. Memphis, here we come.

The 302-page, 6″ x 9″ hardback and e-book, containing 30 historical photographs, will be published by BMG Books on August 11, 2020.

Order Knock! Knock! Knock! On Wood: My Life in Soul from BMG Books now.