Editor’s note: Don Wilcock is currently writing his memoirs, looking back at 51 years starting with Sounds from The World, a column he wrote for “grunts” in the rice paddies of Vietnam in what was then the largest official Army newspaper in the world, ‘The Army Reporter.’

I love artists who go against the grain. The ones who see beyond the misplaced attitudes of the masses. Charlie Daniels was such a man. Daniels passed away of a hemorrhage stroke on Monday, July 6th at age 83.

He was a Southerner who wasn’t still fighting the Civil War. He was a popular artist who understood the plight of the drafted veterans of the Vietnam War. And he played music that broke from the clichés of the country hit parade throughout his career, and he did it well.

Daniels played guitar as if it were his last solo every time I saw him take the stage. And he consistently fronted a band that was respected by hardcore fans who ranged from hippies to rednecks, veterans to youngsters, top 40 followers to nostalgia freaks.

To me personally he was one of those interviews with whom I could count on to have an instant rapport. My style of interviewing has always been to begin an interview by becoming my victim’s best friend for half an hour or 45 minutes on the phone. Charlie played the same game. And he played it so well that he made this grizzled veteran feel like he really meant it. He WAS my best friend. He was the uncle from the south I never had. And he cared about me as an individual, and not just a vehicle to get more asses in the seats.

Daniels supported the U.S. military with The Journey Home Project which he founded in 2014 with his manager, David Corlew, to help veterans. The last time I saw him was when he did a 2014 benefit for homeless veterans at the Times Union Center in Albany, New York headlining over The Marshall Tucker Band promoted by my friend Jim Anderson. “We send people off to put their lives on the line for us, and they come back and we don’t take care of ’em. That is unacceptable,” he told me at the time. And this wasn’t just platitudes from a guy supporting a now popular cause.

In 1981, way before it became appropriate for rock stars to support the vets, he did a benefit for the Vietnam Veterans of America at the Saratoga Performing Arts Center. The VVA was ahead of the curve 30 years ago in efforts to get help for vets whose cause was being largely overlooked by the Veterans Administration. I was a member of the VVA at the time and worked on promoting that show. We were not happy. And our cause, later deemed just, was not universally accepted as worthy. We were a squeaky wheel. And, unlike the Me Too movement or Black Lives Matter, we weren’t gaining the leverage that our cause deserved, certainly not among the in crowd of rock fans.

“I learned very early on in my life that there were two things that actually took care of the United States of America,” Daniels told me in 2014. “It was the grace of God first of all, and the United States military. It was that way then, and it’s that way now. As long as there’s a United States of America it will be that way.”

This veteran string master and singer/songwriter won a Grammy for “The Devil Went Down in Georgia” that went No. 1 on the country charts in 1979 and No. 3 on the pop charts. It was voted single of the year by the Country Music Association.

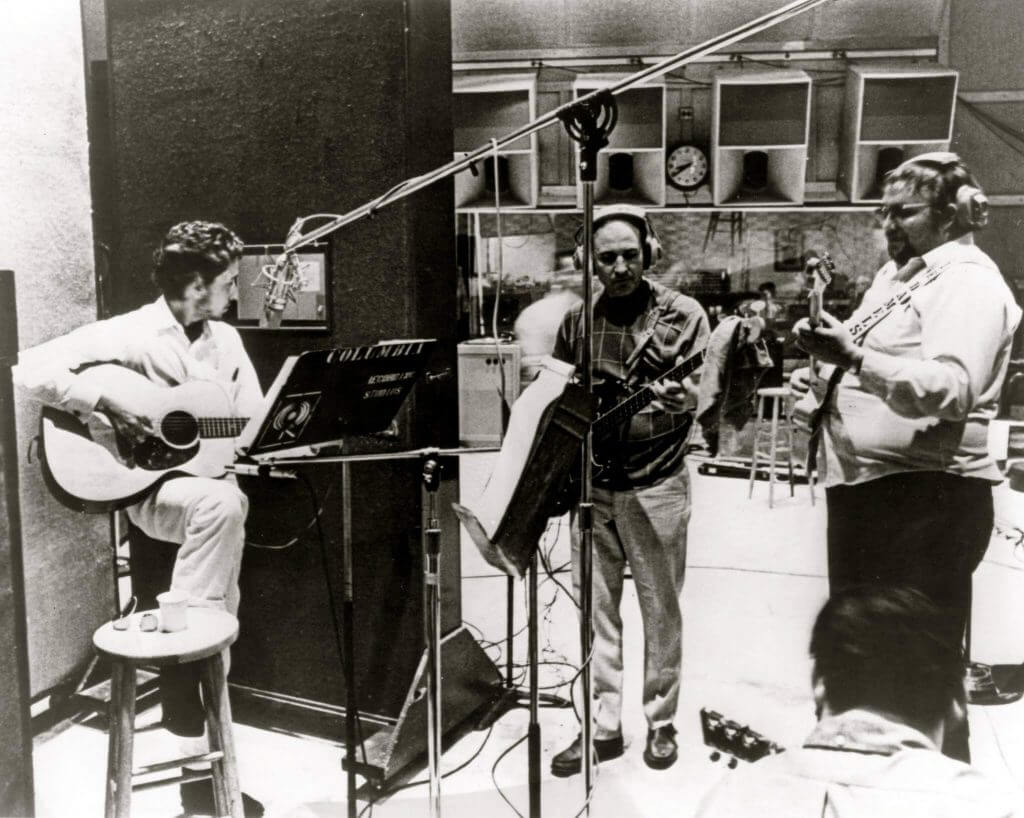

He played guitar on Dylan’s career defining “Nashville Skyline” LP in 1969. The son of a lumberjack who grew up in North Carolina, Daniels listened to the Grand Ole Opry as a kid and toured his first solo album in one van while David Corlew drove the other. Forty-one years later, Corlew is still his manager.

When Jimmy Carter inducted Daniels into the Grand Ole Opry in 2008, the former President stated, “He’s played everything from rock to jazz, folk to western swing and honky tonk to award-winning gospel. In Charlie’s own words, ‘Let there be fun and 12 notes of music make us all one.’ ”

A self-avowed Christian, Daniels told me he’d never hung out in what he called “the show business crowd, the underbelly nightlife.” He was unapologetic in saying “I came from a redneck background of working-class people. I’ve worked in the tobacco fields. I’ve picked cotton a little bit. I know what it’s like, and that’s basically my people. That’s the people I like to be around. And it keeps me grounded. I’ve never had a problem being me.”

That said, he recorded with legendary Nashville producer Bob Johnson who introduced him to Johnny Cash, Leonard Cohen, and Dylan. His latest album at the time of his 2014 concert, was called Off The Grid – Doin’ It Dylan. Songs like “Tangled Up in Blue” and “The Times They Are A Changin’” sound like Charlie Daniels music, not covers of another American classic. One song not on the album is “Lay, Lady, Lay.”

“I played on the original, and it’s always been one of my favorite Dylan tunes,” said Daniels. “But I just couldn’t make it mean anything and get away from that particular arrangement the way it was done in Nashville. So, we just moved on. We tried changing the feel, but it would always go back to are we doing the song justice? No, we’re not. If we do this, it’s gonna be contrived. And we are not contriving this album. So, let’s move along and do something else.”

Dan Rather had recently interviewed Charlie Daniels for his AXS TV show. Rather spent a day with the iconic artist in his studio, on his front porch and on stage at the Grand Ole Opry. “I kept waiting for the gotcha factor,” said Daniels. “I kept waiting for the trick question. I kept waiting for it and it never happened.”

There is no “gotcha” that could trip up Daniels. He was an open book. My favorite work of his is a recitation called “My Beautiful America” where he says: “Did you ever see the early morning dew sparkling on the blue grass / Or the wind stir the wheat fields on a hot Kansas afternoon / Or driven the lonely stretches of old Route 66 / Have you ever heard the church bells peal their call to worship / On an early Sunday in some small town in the deep south?”

I feel like I’ve lost a brother in Charlie. He got to me in every way that only a great artist can. His songs came from deep in his heart. He delivered them with guts and gusto. And he put his beliefs on the line, never yielding to what might be hip at the moment, working to make life better for everyone.

Rest in peace, my brother.