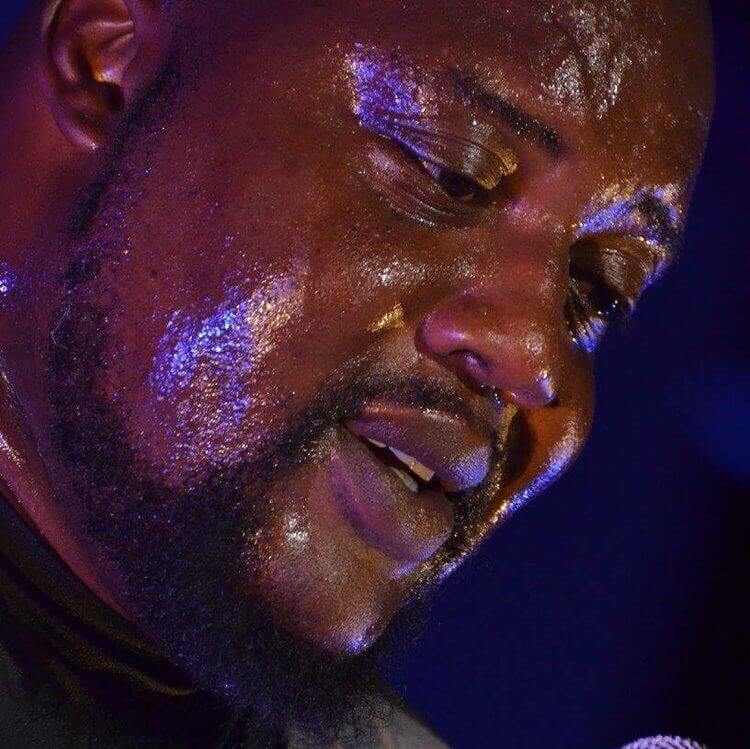

Bluesman Sugaray Rayford, veteran of almost 200 shows a year, across 15 countries and 20-some-odd states, has played some weird shows. But the March 14, 2020 Walla Walla Guitar Festival was notably strange.

“They had sold some 600 tickets and we got there and the governor and the mayor told them that they wouldn’t allow us to have more than 200 people in the room at a time,” Rayford said. “They had police fining them $10,000 a person or something.”

Such was life in mid-March Washington state, the site of the first U.S. confirmed COVID-19 case in January, and the first U.S. death in late February. Rayford was touring the Pacific Northwest on a short tune-up hop to get his band ready for a longer 2020 tour that would take them everywhere from Switzerland to Australia to Russia. As the March swing went on, Rayford noticed the world changing. His two sold-out March 10 and 11 shows at Seattle’s Dimitirou’s Jazz Alley had small turn-outs. “I remember the show before the last night, the owner came up to announce that this would be the last show for the foreseeable future. They were closing down until the end of the pandemic and we were like, ‘wow.’” Things were even worse by the time Rayford got to Walla Walla.

Musicians are like anyone with a career: momentum means a lot. If they’re finding success, they want to keep things rolling. Rayford was rolling. In addition to being booked out for 2020, he had a Grammy nomination for 2019’s Somebody Save Me (Best Contemporary Blues Album). He won two Blues Music Awards (BB King Entertainer of the Year and Soul Blues Male Artist of the Year). Rayford said he thought 2020 was going to be a breakthrough year for him: “I’m saddened by [the pandemic], and this will sound selfish, but I felt like this should have been my year. I worked really hard, and so many people have, but luck had lined things up in a way that this should have been my year.”

Musicians are also like anyone with loved ones: careers mean a lot, but the health and safety of loved ones is always the most important thing. While we were all learning about coronavirus and infection rates, Rayford’s wife was going through her own non-COVID health issues, including cancer. He had taken off November through March to take care of her, returning to the road just in time for the world to shut down. “It’s been really serendipitous, I guess. I’ve been able to be home with her.” As a result, Rayford is torn about the lost momentum, finding a silver lining in the career detour and grateful his wife is on the mend.

But of course, just because the world has closed down doesn’t mean Rayford has completely paused his career. He’s making the most of quarantine. For instance, there’s a new single on 40 Below Records, “Homemade Disaster,” a surf-rock-meets-blues masterpiece with a breathtaking vocal performance that somehow manages to draw a connection between soul and New Wave. While it hints at a new direction for Rayford, and perhaps even, eventually, an 80s-style haircut, the track was actually leftover from Somebody. “We’d already pushed the envelope of the blues so far that we thought maybe it was just a little too far,” Rayford said. “We’ve been writing like crazy, but without being able to record, we revisited it and let a select circle of people listen to it. Everybody was like, ‘Man, this is really cool. Why didn’t you guys put this on the album?’ You know, it’s always Monday morning with people.”

Rayford is also hosting “Sugashack,” a weekly Facebook livestream where he chats with friends from a very nice shed outside of his house (in New York City, it might rent for $2500 a month, assuming it was zoned for decent schools). But, as Rayford points out, his friends are well-known musicians and actors. “I’m allowing the audience to peek in to what happens in the green room.” Beyond star power, though, the show works because of Rayford’s personal charm, a confidence that isn’t boastful, and an ability to make the viewer feel like Rayford is a close friend popping in for a quick video chat. A typical episode features Rayford singing along to his favorite old songs and talking directly to commenters, making a modern enterprise feel very old-fashioned, like the overnight DJ on a limited-range radio station.

What’s interesting about Rayford is that for all his accessibility, he wants to be famous. Or, to be more precise, he wants to reach a certain point of reverence, indelibly etched into music history. He specifically references artists like Keb’ Mo’ and Charlie Musselwhite as being at that level. You’ll notice that Rayford isn’t looking to pop icons Taylor Swift or U2. That’s because he believes in the blues as both an art and as a commercial enterprise.

“The blues is one of those American music forms that’s never going away,” he said. “Its popularity has always gone back and forth.” Rayford also sees the blues in other genres. “[In terms of popularity], country is the elephant in the room at the moment, but then it had a baby and they called it Americana, which is actually a very mixed child. This baby’s got a little black in him, and white, and Irish, and I think that’s the wave of the future.” Rayford is also encouraged by the popularity of blues outside of the United States. “If you’re a blues guy, the thing you have to learn is that you have to be international, because if you only see blues in America, then you think it’s this lost art form,” he said. “But you’ve got to realize that outside of America, blues guys are treated the same as rock guys or hip hop guys.” Rayford’s lived the international life, playing just about everywhere, even Longyearbyen, Svalbard, Norway with a population of 2,638, the world’s northernmost town. “If you use your map when you get to it, the map won’t go up any further,” Rayford helpfully points out. So while the blues can feel lost in the United States, it’s apparently found in the North Pole.

In addition to the livestream, Rayford is finding ways to keep busy without leaving the house (Sugashack has even moved out of the shack and into Rayford’s home because of the summer heat). Any given day involves anything from helping his wife, to writing, to feeding the dog, to perhaps a nap, since Rayford often goes to bed at five and then wakes up two hours later. “There’s no typical, which is hard because as an ex-Marine, I like some kind of structure.” For Rayford, the military was a way out of his Texas town, which is why he thinks so many musicians come out of the armed forces. “Many musicians come from an economic downturn and the military is a way out,” he said. “It takes a long time before you start making money in this business.” Rayford understands the importance of financial stability personally, having grown up poor, with he and his brothers raised by their grandmother after their mother died. His

grandmother still looms large for him.

“I couldn’t watch that movie, The Help, for a long time,” he said. “Because it reminds me of my grandma. I was with her in the corner, or I’d sit outside while she was cleaning people’s houses. It’s too real for me.” Watching his grandmother’s way of life, in addition to his own experiences, has made him appreciate the way the Black Lives Matter movement is making these societal inequities more visible. “My wife is white, highly educated, super intelligent, but she was shocked to see how different things were living with a black man as her husband,” Rayford said. “A guy pulled me over one time, I was in my truck, my wife was with me, and this officer walked up to me, looked in the window, looks at my wife, and he’s like ‘ma’am, are you all right?’ like I had kidnapped her,” he said. “When the officer pulled me over, he said ‘you were swerving.’ And my wife was like ‘he was not!'”

Rayford takes comfort that while older blues songs had to lyrically disguise the conversations around this kind of mistreatment, now these issues are openly discussed. Even though times are slowly changing, his son had to encourage Rayford to talk about his experiences. “I said it just brings up bad thoughts for everybody and he was like, ‘Yeah, dad. But it helps people’.”

And true to form, Rayford is optimistic about the future: “I just wish we get to that point as a nation, and as a people, where we judge people on their merit, not their color, their religion, or even their politics. Just their merit.” While that’s a lofty goal for an unusual summer, Rayford excels at making the best out of challenging situations. And you almost feel like if it’s something Rayford wants, he’s going to make it happen.