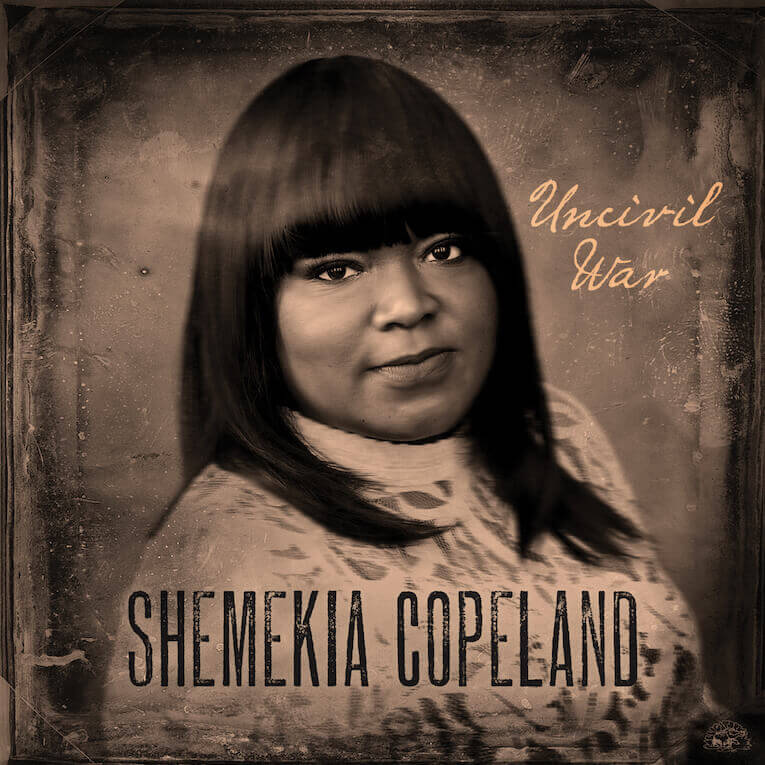

“It’s a shame the hand we’ve been dealt,” says Shemekia Copeland who has just released Uncivil War, a CD that raises the bar height for blues as a genre in its portrait of today’s race relations.

“I once got into it with a black guy (Shemekia is African American). He said that if he had been a slave, he would have just jumped into the ocean and killed himself. And I said, ‘Well, if all of them felt this way, you wouldn’t be here.’”

I try to imagine the world without a Shemekia Copeland and all the other African American artists who make American blues music the inspiration for the sounds that inspire popular music around the world. The idea of giving up in the face of being enslaved then and today in light of today’s racial hostility is a stunningly horrible thought, but the options in pre-Civil War America for slaves was just that stark.

Shemekia’s response to this hypothetical question? “Who is stronger, the one who survived through this and lived so we could live or the ones who jumped off in the ocean? It’s hard these days to think about what you would do in this situation. Those are your options: kill yourself or live so you can be tortured, beaten, overworked, and not be paid for it. Oh, my goodness. This could go on forever.

“I had my DNA done, and I’m 87% African. My mother is 91% African. My ancestors came from off those ships. I wouldn’t exist if they jumped off and decided to kill themselves. I do exist because they were strong enough to live through this. I gotta be strong enough to live through what we’re going through right now. You know? I’m just trying to make sure that happens and in my own way live another day.”

“Clotilda’s On Fire” from Uncivil War relives the horror that slaves endured on the last slave ship bound for America in 1859. It’s a true tale based on an incident in which the captain of the ship burned and sank the evidence of his crime in Mobile Bay, Alabama in 1859, 50 years after slave trade was banned. It was written by Shemekia’s manager/songwriter John Hahn and the album’s producer Will Kimbrough.

“They said if you were caught, they would confiscate your ship, send you to prison, and fine you a lot of money,” explained Kimbrough to John Hahn. “So, this guy unloaded the slaves he brought over from Africa, and set his ship on fire. I thought about it and said maybe we could do a song about it and call it ‘Clotilda’s on Fire.”’

John loved the idea. “Most times I have the title, and all the lyrics, and he has total freedom with the music. The exception to that is an excellent exception for him. He came up with the title.”

John has been writing a significant portion – more than anyone else – of Shemekia’s original material since she began recording in 1998 when she was 18 years old. He’s known her since she was eight.

“It’s funny because we’ve been talking about Clotilda for a while now since they found her a couple of years ago,” says Shemekia. “I think it was 2018 when they found her and the fact that slave ship was probably 50 or 60 years after they supposedly abolished slavery. Then they burned her to hide it, and here I am singing about it. And then the end of it, we’re still living with her ghost. It’s just an amazing story. Amazing story, and I’m here to tell it.”

The daughter of the late blues singer Johnny Clyde Copeland, Shemekia first took the stage with her dad at age six. To her, performing is as natural as putting one foot in front of the other. “You know, it’s funny. I’ve always had the ability to jump into a song. It’s almost like you have to be an instant actress. Even when you’re on stage performing, you gotta jump into that song and become that song. I’ve always had that ability to be able to do that, and the lyrics for me have always been so, so important that I want to make sure they come across properly.”

John Hahn first met Shemekia as a child when, as an ad man for BBDO, he produced a bank commercial featuring her father singing a jingle. The day her father died in 1997, John took her for a walk. In our interview, Shemekia took me back to that day. “I didn’t know what to feel. In my mind, I’d just lost the only man that was ever going to love me and take care of me. And I felt at that point I needed to take care of myself. That was my mindset. I went for that walk with John never really thinking where we would go from there, or what we would be at that point, and that day was just a hard day. A lot happened quickly after that.”

John today says it just this simply, “Shemekia is my daughter. I’ve known her since she was eight years old. She is 41 now. I walked her up the aisle. I was great, great friends with her father. I left her father’s bedside at 10 o’clock one night and the next morning he died at 8 a.m. So, I have very great feelings about this. And it’s a challenge.”

John infuses Shemekia’s spirit when he writes her songs. Shemekia says it this way: “I do believe there’s an old black woman inside of him that had a whole lot to say and never got a chance to say it, and she’s using him as a vessel because things come to him that way I do believe. You know, I think over time it’s like any relationship. No matter who it’s between has to be nurtured. I don’t care if it’s your biological parents or your biological brother or whatever or just a good friend. You and I both know we have friends we’re closer to than our own family. But it just happens organically over time for me.”

John likens writing for Shemekia to walking a tight rope. His songs for her address the stark reality of racism with empathy but not anger. And he never loses sight of the need for her songs to be entertaining. This is not a sociology lesson, he says. He gets inside her head and writes about contemporary universal issues in a way analogous to classic delta blues. White artists like The Moody Blues couldn’t relate to “sleeping under a hollow log.” Field hollers addressed issues in code. But few blues artists today can talk about heartache and trouble unless it’s intimately connected with a romantic relationship. John does it not as strident as society as a whole is about politics, black lives matter, or me-too, but from a universality that tacitly recognizes that we’re all in this together.

“It’s a very fine line,” says John Hahn, “between expressing what you’re really feeling and trying to do some good, and at the same time not finger pointing at other people, saying they’re bad, and I’m the only one who knows what’s going on. In that same vein, it’s tough to write in an entertaining way about social issues without lecturing and being patronizing.

“Racism is still there. The environment is a horrible problem, and gun control is a serious problem,” says John Hahn who has given Shemekia songs about each on this album. “And if you’re spiritual – I don’t want to get too heavy here – but is your Jesus a forgiving Jesus or is he a judgmental Jesus? So, there’s many things that the blues today in contemporary life that surprises me that other people don’t write about.”

Uncivil War takes another step forward in moving the dial for blues in a more eclectic direction – particularly toward Americana with Will Kimbrough as producer – and with contributions by artists as disparate as Webb Wilder, Jason Isbell, Jerry Douglas, Steve Cropper, and Christone “Kingfish” Ingram.

“Blues artists should be able to take advantage of the other instruments and styles of other so called genres that have borrowed or have been born or borrowed from the blues and are blending it up using it to our advantage and keeping our music fresh and introducing people to new forms, new sounds so it just works out,” says John Hahn.

“So, the good thing about where Shemekia is now in this Americana is that her horizons have broadened and opportunities have opened up for her, and it’s refreshing that just because she does a song with people not normally associated with the blues – it could be Jason Isbell or John Prine or Emmy Lou Harris – The blues community didn’t give up on us or think we had sold out. Because we hadn’t. We were trying to give meaning to that overused expression “keeping the blues alive.” Let’s get rid of that expression. It makes it sound like the blues is in the intensive care unit somewhere.

“In the title song “Uncivil War,” I wanted to address the challenge we have in that almost exactly 50% of the country, at least at this point before the election, seems to have views that are diametrically opposed to each other. All these very serious bad words are tossed around whether it’s on the side of the fence of dictatorship or, if you’re on the other side of the fence, dirty words like socialism.

“It leaves each of us in the position where we have a choice. We either accept and respect the values of people who have been our friends forever and at the same time possibly lose a little respect for ourselves because we feel like hypocrites for not starting a fight at the Thanksgiving dinner table.”

Shemekia: “Anybody can put an angry song out there, but anger doesn’t get us anywhere. It just turns us off, and it makes (fans) not want to listen to you or hear you, but if you can come up with a way to get your message out there without that, you surely will have more people willing to listen.”

*Feature image: Mike White/Alligator Records

Order Uncivil War

Shemekia Copeland