The early 1960s Chicago blues scene was surprisingly large. So big, that two young white kids from the South — harmonica legend Charlie Musselwhite, out of Memphis, and guitarist Elvin Bishop, raised in Oklahoma — didn’t know each other.

“It all depended on the exact people you hung out with and which clubs you got in the habit of going to,” Bishop recalls. “[Charlie and I] were on a different circuit. We were kind of acquainted and we liked each other. And I liked his music always, but our paths didn’t cross that much.”

The two would eventually strike up a friendship, though, and finally, in 2017, they cut a track together: 2017’s “100 Years of Blues” for Elvin Bishop’s Big Fun Trio. “We were on a package tour with our own bands, but part of the show was me and Elvin just sitting down together and doing a few tunes, just the two of us,” Musselwhite says. “And it went over really well. I don’t remember who thought of it first, but somebody said, we ought to have a CD for sale out there in the lobby.”

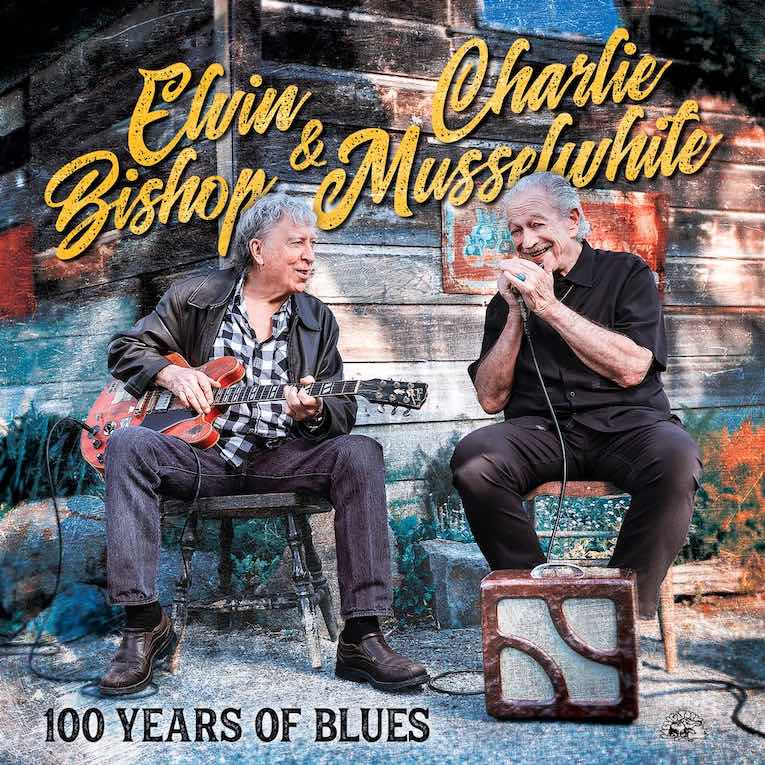

That led the two into the studio where they cut 100 Years of Blues, which is the two blues legends joined by pianist/guitarist Bob Welsh (from Elvin Bishop’s Big Fun Trio), on a relaxed set of songs that makes you feel like you’re hanging out at a late night/early morning jam session in someone’s living room. Not many artists could pull off that kind of stripped down album, recorded live, like a show, leaving little for anyone to hide behind.

But not many musicians have their pedigree. Bishop was a founding member of the Paul Butterfield Blues

Band, with a long solo career that even saw him land a song, the gentle “Fooled Around and Fell in Love,” off of 1975’s Struttin’ My Stuff, in 2014’s Guardians of the Galaxy. And Grammy Award-winning harmonica legend Musselwhite, while less connected to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, was discovered by none other than Muddy Waters in Chicago.

“I had already met [Waters] once in Memphis when I lived there,” Musselwhite recalls. “And then when I was in Chicago, I was going to his home club, Pepper’s Lounge. When he wasn’t on the road, he would be playing at Pepper’s Lounge and he lived just around the corner. And so I hung out there a lot. And he thought of me as a fan, because I’d request tunes and talk to him, but I wasn’t going around telling people that I played harmonica and wanting to sit in or anything. I was just happy to be there and listen to them: my heroes.”

Musselwhite’s story could have ended there, except that a waitress told Waters about Charlie’s harmonica playing. Waters called him up to the stage one night and made Musselwhite’s career. “All these other musicians heard me and man, they started offering me gigs and gosh, that sure got me attention,” he says. “And that was a big turning point right there.”

Musselwhite credits his and Bishop’s southern roots with their acceptance into the Chicago scene. “One thing about Elvin and I being in Chicago is we were from down home, in their eyes,” Musselwhite says. “I was from Mississippi and Elvin was from Oklahoma. And I noticed that when these guys would introduce us to other people, to friends of theirs, they’d always say, you know, ‘Charlie, he’s from down home.’ And that meant something. I wasn’t a local white Yankee guy,” Musselwhite laughs. “There was a difference.”

Now Bishop and Musselwhite are the experienced blues artists, with 100 Years of Blues showing that while there’s over a century of playing between the two of them, they still have new things to say.

Steven Ovadia for American Blues Scene:

What do you like about playing with Charlie?

Elvin Bishop:

Well, he’s one of the few guys that really understands the real deal blues and how to go about it. And I like him because he’s one of the few guys our age that’s still progressing and trying to work out new stuff [laughs]. Most harmonica players, what you get when you play with them is recycled Little Walter licks they learned off records and there ain’t none of that with Charlie.

Do you think it’s different with guitarists?

Elvin:

It’s a matter of the individual. You hear some guys that’ll stick pretty close to Albert or B.B. King, or play real recognizable licks and everything. And then guys who come up with their own stuff. So it just varies with whoever you talking about, you know?

How would you compare playing with Charlie to playing with Paul Butterfield?

Elvin:

They’re both one-of-a-kind dudes. And they’re just totally different individuals. In my opinion, Butterfield was at his best when he had the 12-bar blues framework to work inside of. And then he kind of got interested in doing all kinds of other stuff. And it sort of spread out all over the place and I think his strongest, most direct impact was playing 12-bar blues. And he had a good knack, like Charlie, of playing something genuine and strong, but not other people’s licks.

What do you like about playing with Elvin?

Charlie Musselwhite:

We have the same influences. We love music the same way. And we probably knew all of the same blues guys that were so encouraging to us and welcoming, and flattered that we knew who they were and would go to these rough little clubs to see them. So we have a lot in common and playing together is just so effortless. It’s like we’re of the same mind. So we’re kindred souls.

He’s an old friend. We’ve known each other since we were kids practically. In our 20s or maybe even as teenagers; I’m not sure when we first met. I know I got to Chicago when I was 18. And I think Elvin was already there, like another year or so before me. And we both love blues in the same way and feel the same way about it and had many the same friends and listened to the same music and went to a lot of the same clubs. Even though we didn’t live near each other or see each other all that much in Chicago, our paths did cross.

And so we were in that scene, we were a part of it. Only difference was we were young white guys, and other black guys our age didn’t want anything to do with blues. You know, I tell black guys my age about Muddy Waters or Howlin’ Wolf, and they say ‘What’s wrong with you? You’re crazy. That’s old folks’ music.’ I say ‘I like Sonny Boy Williamson’ and they say ‘Sonny Boy Williamson! Man, that’s my parents’ music.’ The blues was just adult music. You didn’t see people our age, black or white, really, in the clubs.

What would you say makes like for a great guitar lick?

Elvin:

I like to hear people being themselves. And somebody that has an identifiable personality. You spend a lot of your time when you’re learning your basics and getting your tools together when you’re younger, imitating other people, to be honest. Most people. Just learning the vocabulary and all that. And I think the great majority of players never get past this stage.

When you think of like a blues guitar personality, who do you think of? Who’s got like a distinct voice?

Elvin:

You’ve got to start with B.B. Definitely he came up with some highly original stuff that really, really worked. And Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Lee Hooker. Guys like that who are just totally different from anybody else. I mean, you’ve got to admire those guys. I remember I’d go in Pepper’s Lounge to hear Muddy Waters and those guys. And on the jukebox, they’d have ‘Mojo Hand’ by Lightnin’ Hopkins and that’s one guy with a guitar. And this is way back in the 60s, but still getting played on the jukebox. I said, ‘Now that guy. He’s got something that people like, you know? He’s the original thing.’

What do you think goes into like a great harmonica line, Charlie?

Charlie:

Well, there’s different ways of thinking about it. Some players, and it’s not just a harmonica, it’s all instruments, they seem to think the faster you can play somehow proves something. I don’t know what that’s about [laughs]. They treat it as a sport or something. Or sometimes, I wonder, are they in a hurry to get to the end of the tune? They play all these notes and all this technique and it makes me think of somebody that has a huge vocabulary, but really nothing to say.

So for me technique is important, of course, but it’s not what comes first. You use technique to support the music. For me, the music comes first. I love melody; a line that just speaks to you on a level beyond language. And sometimes when I’m playing, I have the feeling that I’m singing without words. So it’s like a language. And different people have different ways of expressing themselves with that language.

Do you always have a harmonica on you?

Charlie:

No. I have some on my desk. That’s where I keep them [laughs].

Charlie, you played slide guitar on “Good Times.” I was a little surprised. Have you played guitar on record before?

Charlie:

Oh, yeah, many times. I even put out a whole album of guitar music. It’s on my own label: Henrietta Records. And I have one in the can that’s all guitar, with a drummer. I recorded that in Clarksdale, Mississippi.

What makes you decide to pick up a guitar versus harmonica?

Charlie:

I’ve always loved both and I started playing both around the same time, when I was about 13 or so. When I got to Chicago, there were tons of guitar players and not that many harmonica players, so that’s why it was easier to take the harmonica route for me. But I kept on playing for my own satisfaction. The truth is if I had never had a career in music, if that waitress had never told Muddy that I played, I’d still be playing. It’s just something I do. I was just fortunate that I was able to have a career doing that.

Your guitar playing is bluesy, but also very atmospheric.

Charlie:

My style of playing is more of a country blues. It’s more down home, because after my career started going, I really devoted my attention to harmonica more. And my guitar playing sort of leveled off in a sense there. So I’m still in that down home mode [laughs]. I used to play with a guy named Robert Nighthawk. He was a slide guitar player, and watching him, I just figured out the patterns he was using. And it was easy for me to pick up his style, which is the same Earl Hooker later on used too, for slide playing.

How would you rate Charlie’s guitar playing, Elvin?

Elvin:

He played some hell of a slide. At times I felt like the third best guitarist on that album, because, oh that was beautiful what he played on that tune. And Bob Welsh, the guy who was on the album with me and Charlie, playing piano and guitar, is just a hell of a musician. He’s really great. And he contributed a lot to how solid the whole thing was. And I like the album because it reminds me of how blues was before even Chicago blues. It’s like down South when they they hadn’t even added drums and the bass to the thing. Just guitars and harmonica.

The blues is so structured. So how do you find something new to say?

Elvin:

I’m the type of guy who’s never been able to sit down and write a song. It just happens when it happens. And it’s when strong feelings about something sort of squeeze one out of me. That’s just what it amounts to. And you can put any words to the structure. And blues is actually a real good thing to have at your disposal in times like these because it was invented by and for people who lived in relatively impossible circumstances. It’s a way of helping you survive and get some fun out of life during real rough times.

Charlie:

Actually, it’s just endless. You can say, ‘Well it’s just three chords, and the blue scale.’ But John Coltrane and Thelonious Monk recorded tunes that were just three chord changes, but boy did they find some new ways to go! And I think people that consider it simple or something are missing the point. You listen to a guy like Jimmy Reed and that sounds like so simple. But boy, show me somebody that can do that. Nobody can. You can say you’re doing it, but it doesn’t sound the same. It just doesn’t get there. You can play all the notes and make all the chord changes you want to, but if you don’t have the feeling, if you can’t put the grease in it, or if you don’t even know what that is, it’s just not going to happen.

Are you writing a lot now? Given the moments that we’re in?

Elvin:

You would think that I would be but relatively little is coming to me right now. So I’m just hitting the guitar a couple of hours every day in my studio and seeing what I can come up with and just hoping and trusting that the improvement will show up later, in some kind of way. I did one video, though.

What’s your writing process, Charlie? Do you think in terms of harmonica lines?

Charlie:

No. Mostly I’ll think of lyrics. An idea. A feeling. I describe that feeling or that idea and try to make it rhyme and make it…I hate to use the word catchy, but appealing [laughs]. I want to get your attention. And I want to have feeling and depth to it. Substance. The harmonica playing comes with the recording. After I get the tune down, then it just seems natural as to how to begin it or play it and how to play around with it. But sometimes I think of melodies that I would like to play, like as an instrumental or something.

I keep notes. Like I have piles of napkins and matchbook covers and pieces [of paper]. Garbage bags of something I wrote on when I didn’t have a suitable piece of paper. Just a little sentence or something that I’ve thought of or I heard somebody say something that made me think of something. And when I’m writing, and I’ll have a couple of lines, I’ll pull out those little pieces of paper and start looking through them. And often I’ll find things in there that fit perfectly with what I’ve already got. So that’s why it’s a good reason to keep all those little pieces of paper.

Elvin Bishop Facebook

Charlie Musselwhite Facebook

*Photos courtesy of Alligator Records