If you remember him at all, you probably think of Little Richard as the piano-pounding manic madman behind “Tutti Frutti,” the pompadoured pretty boy who put the rock into roll, screaming his way up the charts in the mid-’50s — challenging Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis to a bar height of excesses they could only dream of reaching.

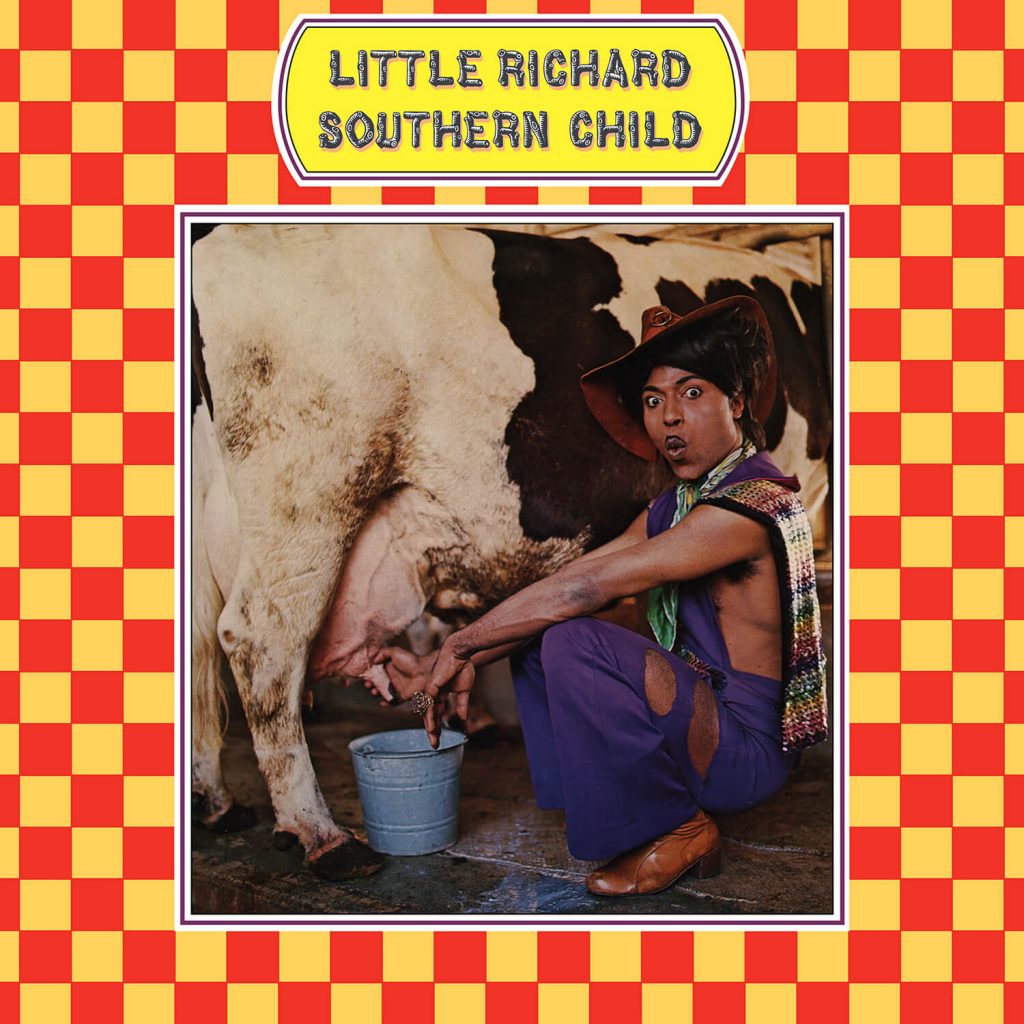

Southern Child (dropping on Black Friday), along with four other Little Richard retrospective albums already available, will forever change the general view of “the architect of rock and roll.” Southern Child is being released on yellow vinyl. It is an album of country music originals Little Richard recorded for Reprise Records in 1972. Yeah, you read that right. I said country!

The timing is appropriate. Friday, November 27th also happens to be Record Store Day. Southern Child was never released in any form until 2005 and then only in a Reprise Records retrospective. It’s the last of five recent Omnivore Records’ Little Richard reissues and will be available in CD format on December 4th. Already available are The Rill Thing, The Second Coming, King of Rock and Roll and Lifetime Friend. Together they represent a body of work that proves Little Richard was far more than a one trick pony who put white artists like Bill Haley and Gene Vincent on notice that they didn’t start the explosion that set kids dancing on American Bandstand. Little Richard did. “Good Golly Miss Molly” and “Slippin’ and Slidin’” sold the most records, but he moved way beyond those early sounds.

“If we don’t throw stuff into the future, it’s going to take someone like me 100 years from now to rediscover some of these things because I look at it as sort of the digital chasm” says Cheryl Pawelski, the Grammy-winning co-founder of Omnivore Records and the visionary behind these five rereleases. She’s spent 25 years “preserving, curating and championing some of music’s greatest legacies.”

Richard Penniman (his real name) told me in 1986, “I’ve never stopped. If you notice, you constantly see me in the media somewhere because I figure if water falls on a rock long enough, it’ll break it. But it has to be consistent. Consistency counts, you know. I’ve put up an umbrella to catch the water. The water has stopped falling on the rock. The rock was almost broken, but it still prevails.”

Southern Child was never released in any form until 2005 and then only in a Reprise Records retrospective. This last of five recent Omnivore Little Richard reissues will be available in CD format on December 4th.

“You know we went from configuration to configuration (vinyl records, cassettes, eight tracks, CDs, and streaming) in the 20th century, and some stuff was rightfully left behind,” says Pawelski. “And some things were wrongly left behind. If we don’t catch some of those right now, they’re not going to be digitized, and they’re not going to be thrown across this chasm. It’s going to take people a long time to root this stuff out and find it again. So, I’m trying to throw as much of this across as I possibly can.”

The overarching impression I get from listening to all five of these recordings is that Little Richard’s best remembered hits were a tiny fraction of his recorded legacy, that he should be remembered with the same level of awe and respect we accord Ray Charles and that Little Richard’s frequent verbal insistences that he was being minimized by pop music media were warranted.

“I’m not the founder of rhythm and blues,” he told me in 1994. “Sonny Boy Williamson, Muddy Waters, Guitar Slim, John Lee Hooker and Fats Domino was playing blues at the time. But I am the one who took rhythm and blues and made it into rock. Rhythm and blues is the foundation of rock and roll, you understand me? I’m the innovator. I am the emancipator. I am the originator and the architect of rock and roll. I didn’t say nuthin’ about no king and all that. The architect!! You understand me?”

At the time in 1994, Little Richard was touring with a crack band that included the great Travis Wammack, guitar player and songwriter who plays on several of these five new rereleases. “We’re still doing it, and we want everybody to come out and see it,” Little Richard begged. “See history alive! Don’t just read about it. Don’t just hear about it. Come out and see history alive. The originator! The emancipator! The architect! And just see it for yourself and watch this old guy that still looks good walk out on that floor and let go. You can ask for no more.”

These albums prove that his braggadocio was not simply hyperbole. The body of work here, which only represents a fraction of his total recorded output, exhibits not just simple eclecticism but is cumulatively outstanding with aspects that border on genius.

Southern Child recorded in 1972 was produced by Robert “Bumps” Blackwell, the same man who produced Richard’s mid-50s hits on Specialty. He wrote or co-wrote all 14 tracks. Bill Dahl, who wrote the excellent liner notes to all five reissues, says it succinctly: “Unlike his 1950s rock ’n roll pioneer peers who stuck with the tried and true approaches that made them legend in the first place, Little Richard wasn’t scared to take stylistic chances in the slightest.”

The songs here have me flashing back on Ray Charles’ “Georgia on My Mind” and “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” and the fact that Reprise never issued Southern Child is a glaring example of the corporate record industry’s emphasis on profit over art. This is great work, but how do you sell a black banshee singing mainstream country with a Georgia twang to a market that only knows him as a guy who plays piano with his feet?

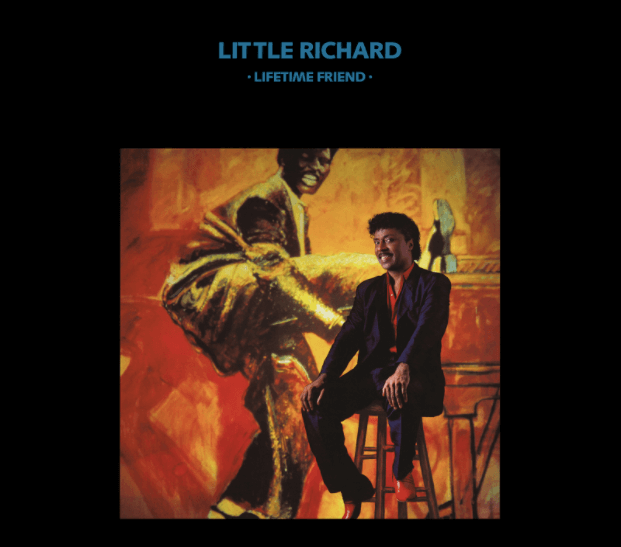

Lifetime Friend, released in 1986, also was produced by Blackwell in L.A. with top session musicians. It is loaded with subtle references to religion that had helped Richard in his struggle against drug addiction.

In 1994 he told me that he tried in his career to separate his music from his Christian beliefs: “I love God and I’m just grateful to God. I know without him we can’t do nuthin’. I learned and now I understand that religion is my personal belief in God and my personal faith in God, and I learned rock and roll music is my living. This is my craft. This is my form of art I present to the world, and this is how I make my living, and so its two different things altogether.” Richard had released gospel records between the time he left Specialty Records in 1957where he recorded his biggest hits and 1970 when he joined Reprise.

Lifetime Friend opens with “Great Gosh A’Mighty,” an alternate take on a song from the soundtrack of Down and Out in Beverly Hills, a Richard Dreyfus film in which Little Richard appears as Orvis Goodnight, a character not unlike himself. In this version he clearly sings “Great God a’mighty” while the background singers enunciate, “Great gosh a’mighty.”

Throughout, he presents his religious beliefs “in code” with references like “You know he’s always on time/He’s the man who holds me in his hand/He can change your life” from “Operator” and on the title cut: “I thank you for helping me find my way/You gave your life to set me free/As long as I live you’ll always be a lifetime friend of me.”

The Rill Thing was his first Reprise LP recorded in 1970 live at Rick Hall’s Fame Studios in Muscle Sholes, Alabama, the home of hits by Aretha Franklyn, Joe Tex, Wilson Pickett, and Etta James. The title cut is in a “Shaft” smooth cool mode. The single “Freedom Blues” went to number 47 on the charts. “Greenwood, Mississippi” sounds like Creedence Clearwater Revival. There’s a cover of the Beatles’ “I Saw Her Standing There” and nowhere to be found is the patented pounding piano.

The Second Coming best lives up to the hyperbole of the five LP titles. Blackwell produced the session at the Record Plant in Los Angeles with a sharp group of sessions musicians. Released in 1972, it finds Richard in fine voice even if he sounds nothing like he did on his ’50s hits.

The King of Rock and Roll was recorded with a studio band in L.A. and sounds like it. Produced by H.B. Barnum who wrote the title track, the rest of the album consists of covers including The Stones’ “Brown Sugar,” “Midnight Special, ” the Temptations’ “The Way You Do The Things You Do” and Hank Williams’ “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.” If that sounds like a hodgepodge, it is.

Little Richard was way more than a novelty, and these releases prove it.

Of his touring band in 1994, he said, “I think that if it means you make less money and a better band you should do it to give your audience the best.” The same can be said of his recordings.

“When you’re out there for the money, you just pick up anything. It’s more than that. You’re supposed to love your craft, and you’re dedicated to what you’re doing. I care about what I’m doing, and I think a person should become a perfectionist to make sure that things are perfect with their music. It should be the best that you can give.”

*Feature image: Specialty Records Archives