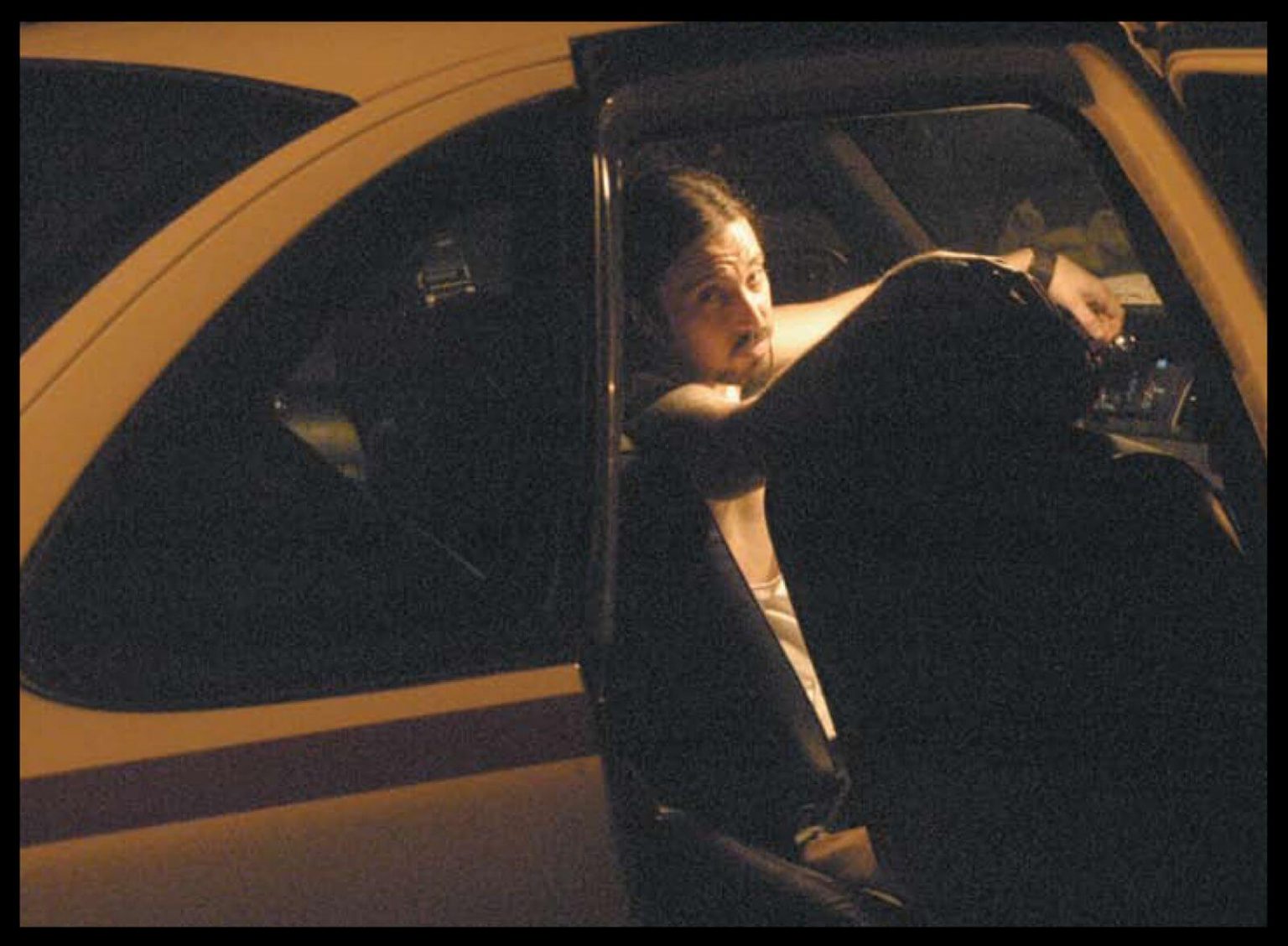

Singer/songwriter/dobro player Dege Legg knew it was time to leave cab-driving when his dispatcher sent him to pick-up a fare trying to escape from what appeared to be a fast food slave camp housed within a trailer park.

“I’m standing in a trashed-out trailer park, surrounded by poor people from other countries, working at jobs they hate, which in turn makes me realize I’m starting to hate my own job,” Legg writes in Cablog: Diary of a Cabdriver, his five-year journal of driving cabs in Lafayette, Louisiana. “I’m one of them! Maybe I no longer have the heart and soul to do this cab-driving shit.”

Legg, also known as Brother Dege, is famous for “Too Old to Die Young”; a foot-stomping country blues track which appeared on Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained soundtrack. While the soundtrack didn’t make Dege a musical celebrity, it gave his music career a solid boost four years after he stood in that trailer park, realizing he no longer wanted to drive a cab.

However, Legg knew he wanted to tell his night shift cab-driving stories. He blogged them and wrote a long, popular feature story for Lafayette’s The Independent Weekly, where Legg subsequently landed as a writer. “People like seeing the dirt that’s underneath the fingernails of their own hometown,” Legg says of the initial cab stories. “So I just kept collecting those stories, knowing that eventually I’d get it together.”

Those stories, once assembled and edited down from 500 pages, became Cablog, a book of short vignettes about those late night/early morning cab rides through Lafayette.

The entries are judgment-free sketches describing his passengers, as well as his interactions with them, which take place between 4 PM and 4 AM. While there’s a fair amount of drug and alcohol abuse in many of his fares, there are also ordinary people without cars, or unable to drive, going to doctors and supermarkets. Legg develops his journalistic eye, crafting a sense of the person and the vibe of the cab in a few pages.

Legg himself is present in every story, but he’s rarely the focal point, more a narrator with a meter. “[The passengers] contributed to the kind of rapid-fire nature of the book, with entry after entry, similar to actually riding and driving in the cab” Legg says. “It’s a waterfall of images and people and characters and things. And it moves pretty fast.” Plus, not much was going on in his life at the time. “The passengers kicked my ass as far as story line goes,” he says.”I just seemed to slow things down.”

The stories aren’t warm, and Legg doesn’t have the opportunity to understand the people he ferries around town. But even with those limitations, Legg unearths a strong strand of humanity. “People walk in the door [of the book] with the kind of typical kookiness that you would imagine accompanying a job like that: drunks and drugs and prostitutes and night life,” Legg says. “But the Trojan Horse is the authentic communication in moments of quiet, the interaction that gets slipped into the book, that give it a heart and soul, rather than just a Taxicab Confessions kind of thing.”

Those moments of connection weren’t enough to keep Legg in a challenging job, so he moved on to other things after that 2008 night, and the distance between then and now allows Legg to write about the experience without being too caught up in it. While some of the stories get at Legg’s emotions, perhaps most chillingly one in which he’s robbed at gunpoint, most of them almost read like a dream journal, where the writer isn’t sure what’s real and what isn’t, so they faithfully transcribe everything they can recall. The surrealism makes it a tough book to put down.

Legg continues with his music, though. He’s working on a new album featuring piano. “I’ve got two metal resonators and I love the sound of them,” he says. “They’re really different. They ring like church bells. I [thought] it’d be so cool to have a grand piano kind of peppering this in a way that’s almost experimental and minimalistic—not so much Liberace—for these songs that are more self-reflective and kind of quiet.”

Legg knows it’s a departure from his now-signature sound, but he wants to keep pushing himself creatively. “I don’t want to [remake] Folk Songs of the American Longhair, which is a record a lot of people like,” he says. “I don’t want to make the same one over and over again because then I get bored. And I don’t even know if it’s possible to make that same record over again. So I keep searching and exploring.”

Which is good. Because while search and exploration make for great music, they make for long and expensive cab rides.

Steven Ovadia for American Blues Scene:

I loved the book.

Dege Legg:

Thanks, brother. Yeah, it’s fun. I wrote that thing almost 10, 12 years ago and had to go through 45 revisions and finally got it out. So, really, it’s like a record that I had sitting on the shelf, and I never put out before. I’m pleasantly surprised people are digging it.

When did you start thinking about putting the book together?

Theoretically, I always knew I wanted to format it into a book. But seriously, maybe around 2009, 2010. And then around that time is when I got the first Brother Dege record out, and that thing kind of ran [well] for an independent release. Cut to a year and a half, two years later, the ‘Django Unchained’/Tarantino stuff happened, where he put the song in the movie, and then that lit a fire onto that. So I had to devote more energy to rounding up the horses and working that, building some speed up on the momentum of the Tarantino stuff. Which I had to do almost completely by myself, because I don’t have a big management team, a label team, publicists, or even traditional old-school distribution. So I had to pretty much just get in the van and go work it and kind of keep albums in stock and do that stuff.

Which is great. It’s actually worked out well as a slow growth kind of thing. [The soundtrack placement] did not hurt the career, but it also didn’t make or break me. It didn’t make me a household name and therefore I didn’t become yesterday’s news a few years after the movie. Like everything, I just kept doing albums, and it’s built on the momentum of the songs and all those things.

I like to do both the writing and the music, but the music ended up taking, specifically for the past eight years, a lot of work. Touring and bouncing around and in between those tours, I would pull out the Word file and take a whack at it, get sick of it, get away, and pull it back out again. That’s half the job. Writing is an unhealthy profession. You’re sitting at a desk for hours to determine anything. It’s like deadlifting 1,000 pounds over your head, just trying to get something done, but I knew I’d eventually get there. And the pandemic created a nice window for me to finally finish it.

Were you journaling from the beginning? From day one?

Pretty much yeah. I mean, I’d already established this format of writing, which I call the column format. It looks like poetry. And you’ll see some of that in the book. It’s the prose when you’re looking at entries. I’d been doing that with my my old band Santeria, documenting a lot of the craziness that happens with bands, not so much the actual shows, you know, ‘Hey, we rocked, everybody loved it, blah, blah, blah’; but more so the weird shit that happens in between the gigs, which to me is the funnier stuff.

And so I’d already been doing that. So I just adapted that format and that style of journaling to the ‘Cablog.’ Right away I just knew. I had a feeling. It wasn’t even a feeling, it was just as soon as I walked in [the cab company] and I met the boss. He was an interesting character. I’m walking out the door, two or three cab drivers are coming in to start their shift, and they’re interesting in an odd way. So I just knew I was going to end up being able to kill two birds with one stone, which is what I like to do, because living the creative life in the deep South, it’s a hustle, man.

You talked about that column format, and how they’re almost like poems. When you sit down to write is it songwriting versus journaling? At what point do you decide what the what the work is?

They are definitely two different beasts. With songwriting, it’s a lot different. It’s less narrative storytelling and more dreamy musing where I superimpose photographs on top of one another, and images and into some kind of abstract, coherent whole. It’s fun, I really enjoy that. And you’ll notice a lot of my songs aren’t too narrative driven; they’re a little obtuse. I tend to gravitate towards the more artier incarnation of songwriting.

However, in journalistic writing or creative nonfiction, I get to cut loose and I don’t have to worry about melody or meter and I can just riff. It’s almost like improvisation. And sometimes I call it speed writing. Or I pretty much try to cut to the meat and potatoes, skipping a stone across the major details of what’s happening, so that I don’t get bored, and hopefully the reader doesn’t get bored either. And then, when I do feel like going off on some kooky, interesting tangents, I do that too. So they’re kind of separate worlds. It’s rare that I actually take an experience, like something in the cab, and turn it into a song. Even though much of setting and the vibe and the overall barometric pressure of the night in Louisiana definitely seeps into the setting of my songs.

Songs are kind of like Rubik’s cubes. And literary or creative nonfiction writing is kind of like…Monopoly. Songs are so mysterious. You’re trying to say something profound, and with your antenna out into the air, and pull something from the ether, and then stick it in the melodic form, and phonetic form and phrase it. It’s really this tricky little puzzle to make work sometimes. Sometimes it happens really easily, but I think my number one thing with songwriting is just flow and [don’t] sound forced. Because I’ve done it, too. Being a creative nonfiction writer, I’ll write nine verses and I’m like, this song doesn’t need nine verses. This ain’t ‘Desolation Row’ buddy. It’s not ‘The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald’ either. I like to whittle things down, trying to wrestle the mystery of the song thing. It’s more spiritual to me, songwriting. And the book writing is more journalistic. I’m enjoying both.

The Rubik’s Cube analogy implies that songs have a single solution, the way a Rubik’s Cube does.

Maybe it’s a Rubik’s Cube that you never completely solve [laughs]. You just never completely get there. Even my songs that I have on record, and I’m sure other people might think the same thing, they’re never done. It’s an organic thing. And even when my song goes out in the world, my recorded version, somebody might take it and redo it, or interpret it their own way. And much like the Delta Blues was, [they might] create an even better version of it. The same way Robert Johnson, I think, ripped off ‘Walkin Blues’ from Son House, who may have ripped it off from Charley Patton. And they’re all totally different. They’re each unique in their own way. And that song keeps growing.

I love that element of stealing from one another in the tradition and rebirthing. Songs are like plants. They just keep growing and reinventing themselves. They’re never done. I can always hear a better verse that I should have [used]. And sometimes I will change it. I’ll end up mutating what I did previously, because they’re always growing. Even the meaning of the song to me will change over time. I’ll think maybe it was about one thing and it’s actually maybe about this.

Is Brother Dege a character? An aspect of you?

The Brother Dege thing was really just kind of me. It was really closer to my heart and soul and that’s kind of what caught on. So it’s not a character. I don’t pretend I’m some whiskey drinking, beer can crushing, 4X4 driving fool. But I do try to make it visually interesting. Like burning dobros and stuff like that. Because folk music gets boring. I want to reflect my personality in the visual presentation of what’s going on and in the whole package of the dark side of the Deep South. I know [Southern music], traditionally, has always been represented by good times. But my experience of it has not always been good. It’s been a little rough. And I love it here. But it’s definitely got its ghosts.

And I also wanted to ask you about Generating Hope: Stories of the Beausoleil Louisiana Solar Home. How did that come about? That kind of stood out as something atypical in your body of work.

Yeah. I’ve always been interested in living off the grid. That’s something I’d still like to do, just kind of disconnecting, living in the country. Connected with people, but not so much the bureaucratic machinery of everything. So I had a genuine curiosity about it. The universe works in strange ways. I got a call from an architecture professor [W. Geoff Gjertson], who I didn’t know, but we had mutual friends. [Gjertson] was writing this book. I just helped co-write sections of it, and edited it. And he needed some help finishing it. That’s a cool book. It’s an interesting story. And just the whole thing about sustainable architecture, really; I like it. I’m interested in it.

What stops you from living off the grid? Do you think it’s not viable for somebody who depends on publicity? Are there other issues?

No, I mean, ideally, I would like to live off the grid and then also come play around in society and be able to make a living; have the best of both worlds. But maybe able to just at least sleep at night off the grid or something. What’s stopping me is maybe money and materials that would be necessary to build a house like that, and buy the property for it. And the time investment necessary to complete it. I’ve really been go-going the past eight years. And it takes a lot of time.

I don’t know to what extent you can answer it, but how has Uber changed the nature of cab driving?

I’ve thought about it a lot. Yeah. From what I’ve been told, it’s taken a big chunk out of the cab business, but I think they’re always going to be there. I don’t know how much of that is just kind of the industry complaining that there’s a new competitor on the market or actual realistic numbers that are biting into their numbers. But it’s not hard to see that Uber and Lyft definitely took a chunk out of their business in some way.

You were talking earlier about the moments of human connection and it seems like those rideshare apps make it easier to pretend you’re not dealing with people.

Agreed. No argument there. But you know what? It’s like, man, the way the future’s rolling, maybe we won’t even have people driving those Ubers in five years. And I can imagine even cab companies adapting to that as well, like driverless cab vehicles, maybe that’s where they kind of get back further in the game. You go to big cities, you see cabs everywhere. They’re roaming around. In smaller cities, like Lafayette where I live, it’s 100,000 people. It was never overrun with taxi cabs. So I’m glad I don’t have to worry about it too much anymore, that I’m done with that job.

Cablog: Diary of a Cabdriver was released on November 17th, 2020 via University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press