The 2020 election has taken place against a backdrop of uncertainty. The outcome of Georgia’s runoff election will determine control of the United States Senate, impacting President-Elect Joe Biden’s ability to carry out his policies on the most important issues. With key legislative initiatives like health care, stimulus, and Supreme Court nominees on the line, the results will impact everyone in the United States, and even around the world.

To help get the vote out, an eclectic mix of musicians — Rock/soul singer Danielia Cotton, along with Spin Doctors’ drummer Aaron Comess, keyboardist Ben Stivers, and up-and-coming rapper Mickey Factz — have united to energize the voting public that turned Georgia blue for the first time since 1992.

Enlisted by volunteers with the DNC who worked closely with Stacey Abrams during the 2020 General Election, they have released a powerful re-imagining of the Ray Charles classic “Georgia On My Mind.” With updated lyrics dealing with systemic racism and voter suppression, the accompanying music video incorporates archival news footage from the past 60 years to illustrate the importance of the black vote in U.S. political history.

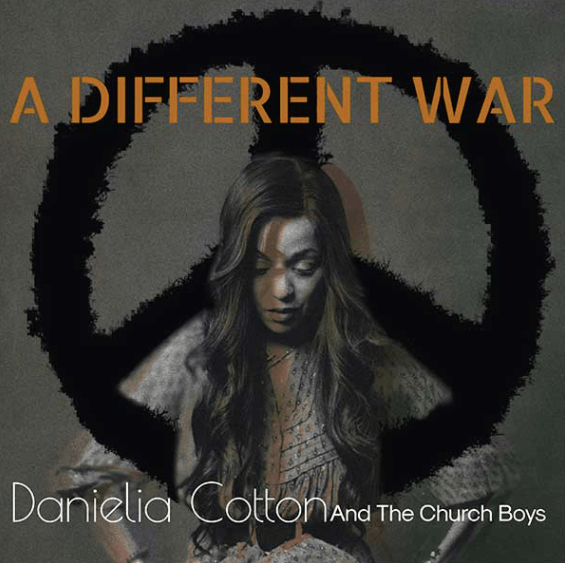

“It was so deep to do it during Covid, too,” says Danielia Cotton of the project and partnership. Mickey Factz, who also appeared on her latest album A Different War, is part of a coterie of socially conscious rappers with a value system that encourages a positive view of rappers — and people in general. “They do what they do, and they feel it doesn’t hinder them being as good as all the other rappers. They’ve chosen a certain way to be. I love that’s his philosophy. He was actually in Atlanta. He just moved to Georgia. It was a crazy coincidence.” Mickey will be featured on another project Cotton is doing that will come out over time.

Pianist, composer and arranger Ben Stivers essentially created the track for the group. “I called him and said, ‘Hey, I want to do this hip hop version of ‘Georgia.’ We spoke about a couple songs — Kendrick Lamar had done a track. And we were thinking maybe like ‘Empire State of Mind,’ but Georgia state of mind. They recorded this in Innsbruck Studio, co-owned by drummer Aaron Comess. “Aaron played drums on my last album, so I texted him and said, ‘Where are you?’ and to come and sort of fatten up the loop. He came down. It was magic and a last minute thing. It was just natural, and he and I worked together on several occasions. Mickey and I have a great relationship now from having worked together the past year on my album, another project, and this. Him being in Georgia and a black man right now, he said yes before I finished the sentence.”

What’s at stake exactly with the senate runoff, and at this time in U.S. history? To Cotton it’s so painfully obvious that the country has taken a turn. As a biracial Jew with a biracial Jewish child, she has seen the racial tension elevate over the past four years, bearing marks of extreme haste that don’t even require a white uniform.

“I grew up at a time when it was deep when I was young. I feel, although I am doing my spot for the democrats too, I think democrats are going to have to widen their view and we’re all going to have to pay attention to those below the poverty line. It isn’t just the upper middle class and the wealthy. There’s the true middle class that’s struggling to stay middle class right now. More than not, most of them are flipping into lower middle class and needing help and going into food line drives. So I just think that’s politically the tone of the country.

“In all honesty, it was a moment where I couldn’t not act. I would not be able to look at my daughter and say in that moment I did nothing. I’ve never felt that way, but I think having a child that’s two and being like, that’s what I did; that’s what I left you. It’s your responsibility to give them a better world. The republicans were for us. Everyone hates to get political in this moment, but there’s a lot at stake.”

As long as there are politicians in question and disparities of the day, there will be songs of protest to address them. You’ve heard the ill-tempered line: Musicians need to stay out of politics. But during times of social unrest and social movements, there is a certain place for music — and that space is given a political focus. Nelson Mandela sums this phenomenon up in one single sentence: “Politics can strengthen music, but music has a potency that defies politics.”

Cotton recognizes this moral imperative of reflecting the times through her songs, and balances the risks and rewards that come with making art. Do you think Marvin Gaye lost sleep over the potential aftereffects of contending in a mellow tenor, “Don’t punish me with brutality”? Was Curtis Mayfield apprehensive about career damage when calling out the opening lines of “(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Below, We’re All Going to Go”?

In the medium of writing, you have the freedom to wield the pen as your cogent voice for the people. Why yield that kind of power to any one person’s shortcoming? “I’ve lost fans. It’s the first time I’ve ever lost people. We became afraid because shit happened when you said stuff. And that’s when we lost our voice. At this point if I lose people, I lose people. But the day I don’t have the freedom and I’m afraid to voice my right to say how I feel, then they win.”

“Music can change the world” sounds like a cliche, but it’s something to believe in when it can change people. On A Different War, Cotton scaffolds a conversation between someone of color and someone who is not.

“I still don’t try to make either side feel like they’re out,” she explains. “I think I was raised in a way that I never felt defined by the color of my skin. Even though I was in a small white town or a college where there were only ten black kids, I still felt defined by who I was.”

Cotton recalls the first time she was called the N-word. She ran home and cried, to which her mom replied, “Oh, Danielia. Stop it. Are you hurt? Are you bleeding? Danielia, there are certain people you can’t change. Change the people you can, and the other ones just keep on walking. Because it’s just not worth it. It’s not going to happen.

“My mother was like, ‘I’d rather be in a foxhole with somebody who’s racist who tells me they’re racist than somebody who acts like they aren’t and they are and they’ll turn around and shoot me in the back.’ The guy who says I’m not for you, but we’re going to fight in this little hole. She said, ‘At least I know where I stand. If you get caught in that, that’ll be something that will take you over.’ Go be who you want to be; go create what you want to create. Who you are is part of how you grew up and your experiences. You are who you are because of the life you’ve lived.”

Citizens and immigrants of color, the intertwined threads of America’s rich cultural tapestry, have experienced strife and exclusion on levels most of us could never comprehend. I relate my story to Cotton’s as the daughter of a Vietnamese refugee who often practiced tough love. We exchanged our feelings about not always being able to open up about things to the extent we wanted throughout our childhood. “I said, ‘You never cared. And she said, ‘Danielia, I cried on the floor of my closet more days than you can say spic. If I let you see it then you would get caught up.’ So they took that bullet for us so we could move forward without that.”

“Some people might say that’s wrong because it wasn’t a strong cultural upbringing in a sense of ‘fight the power that be,’ that kind of thing. She said to just be you without that thing to hinder you. I don’t think that’s necessarily the wrong way to be. I think if we kind of all were that way, but still able to embrace our culture — not necessarily make it a race thing, make it a cultural thing. You eat my food; I eat your food. We talk this way; you speak this way. This is how we celebrate holidays; this is how you celebrate holidays. More like that and less of a color thing, that’s a more unified way.”

The way she sees the world is the way she writes her songs, but A Different War is the first time she’s truly tackled racial indifference. The subjects of gender, wealth, and pervasive emotional trauma also get sorted and harmonized on the EP. “It’s crazy because we are about to go in tomorrow to record another album which I think we should do another EP and put them together as an album with two sides: A Different War and then the other half being A Good Day, which is much lighter. Everything that we’re going in now that I wrote is uplifting.”

During the pandemic, Cotton had what she calls a “white light moment,” a therapeutic time of crawling out of a longtime struggle with the pain of trauma. “I came to the other side of it, believe it or not, during Covid, with an incredible therapist — and just really good work, and willingness to put my shit behind me. Even though we are in this bleak thing, I had a white light moment. The album is very uplifting. It’s sort of like good days — i’m going to give you a reason to believe it’s a good day. The whole album is up and soulful and way lighter than normal Danielia. It’s a nice uplift.”

Pain can act as a conduit for healing. Although A Different War is beautiful to her and an ode to love in that what was affecting her also affected her partner, she also thought it necessary to show the upside of that. “He was my husband; then he wasn’t. Now we’re back together with a kid and deciding if we should get married again. ‘Follow Me,’ which is probably one of the best songs I’ve written in a few decades, is almost Beatle-like. ‘Hey, babe. If you’re going nowhere and you want to go somewhere, follow me.’ The whole thing is about ‘girl you ain’t goin’ there; boy you ain’t doin’ that right. So if you want to go somewhere follow me.’ Everything is uplifting. I’m psyched to do that so that at the top of the new year we’ll release some new music.”

Doing volunteer work in times of Covid, Cotton has learned you can’t be in the streets. And you don’t necessarily see the effect of the video. Even if not firsthand, however, she can still see the fruits of her labor and that the right people are going to respond to the pursuit. “I was a volunteer during the presidential election and I made phone calls. I think people were tired of picking up the phone. They’re inundated; they’ve been asked 19 times every which way to donate money.

“So we did a video that empowered them and educated them while entertaining them. Wow, you can really do this while entertaining. I thought that the beauty of art is that you could do it all under the guise of making people happy. And then I sent the gofundme campaign. That helps, because we did have to get a publicist. A radio promoter is taking it to radio, so there were some initial costs to get it out. And then we figure whatever we raise in excess we will send to Fair Fight. And then half of the single will go to Fair Fight. Because by the time we get the proceeds the election will be done.”

Amid their success, they’ve landed interviews for Stacey Abrams on MSNBC’s Morning Joe and with Anderson Cooper on CNN. “Just being in the Atlanta Journal having our names alongside Lin-Manuel Miranda and Pearl Jam. If they were moved by it then it’s the right thing. You do what you can. That’s all I try to do. I just got approached by a Jewish organization to do something because they saw the video. And I’m like, ‘Alright, I’ll do it.’ Because I’m Jewish.”

Cotton understands that right now politically there are so many things to choose to do. And as far as her craft, she puts her faith in quality over quantity. “You have to put it in perspective. Art comes when it wants to come. You get a curve. You get a break. You get a spurt of ten songs. That might be all you get for another six months until something breaks and you can write something. You can’t force creativity. When you put Songs in the Key of Life on when you were little and you put it on now and you’re like, ‘WHAT?’ It still seems ahead. And Stevie Wonder himself only had one Key of Life.”

She continues, “What I fear with the new generation is there’s talent there, but the vocal acrobats and the pumping out of music that’s seemingly good at the time — but seven months later you’re like, ‘I don’t like this song anymore.’ And even they are going back and loving old music. Because they don’t even know they’re realizing ‘Oh that’s good.’ My nieces are going back and listening to old shit and going, ‘This is amazing!’ And I’m like, ‘Exactly!’ But you’re also raising a generation with constant stimulation. You’re not giving them any moment without anything to just be creative.”

At a certain point she decided she was just going to make her music. After all, it’s her art; not theirs. “And if they get it, they’re going to get it. But I’m not going to compromise my artistic process because people have no attention span. We’re trying to do something here. Art will die — or the quality of art will not remain at a certain level and you’ll keep losing icons. And you will not have those spots filled if you do not begin to allow art to be at the level it should be and you put things on it like ‘You have to have a hook every 30 seconds.’ Because you go into certain songs and it’s not what it is.”

Cotton views all forms of art being impinged upon in parallel with equality becoming less and less. “Art teachers used to say you should be able to draw well before you can even paint. There were standards. Now you can press a button and you don’t even have to play an instrument. It’s deep. I think things will suffer, and we’re then really going to cling to classic shit and old art, and all the great classical music will become even more rare and great.”

She defines her ideal of success as doing it at a level she has respect for herself. “If I have to pass and be dead before someone goes back through my catalog and like ‘This bitch was eclectic, but it was always her.’ Where the industry said she doesn’t know what she wants to be. All those things were me; you just couldn’t see it then. I have to respect my art myself and put my head down and believe that I did it to the level that I felt was what it was. At this point, success is recognition from my peers, which over time I have gotten from the people that I really respected in the world. And I had those moments in my pocket, and that’s all that I need to keep moving forward.

“I was lucky. In the beginning (of touring) I was like, ‘You put me out here with all these old people.’ But then I learned more from Gregg Allman and Robert Cray and Etta James being on the road. Almost everyone I toured with is in the Hall of Fame at this point. I learned so much, and they were by far better than any new bands I opened up for. They were the ones that sat me down. It was incredible. I was so lucky, and I keep those in my pocket and they keep me going. Remember what you’re doing this for — that if you don’t do it you don’t survive.”

Cotton’s writing comes through her, and she follows it like a shadow. If the writing gods are trying to get a message through to you, she asserts you’d better listen or they’ll stop talking. “Rare Child” was written on a napkin, as I imagine lots of great songs have been.

“Keith Richards said he would keep a tape player next to his bed,” she says while also singing “I can’t get no satisfaction.” Continuing, “Woke up, sang it, and then it was on there. That’s somebody that understands that it comes through you.”

Singing and playing also hurtles through her like lightning. “I began to take piano and guitar and go back into music theory and then my vocabulary became enlarged and I was writing differently.” After 17 years of vocal lessons, she can hit notes she couldn’t hit in her 20s. Cotton’s teacher seems to think she is writing beyond her abilities, but in a good way. “I was like, ‘What is this chord?’ I would play the chord on the piano and he would be like, ‘That’s like a C # sus.’ He said it’s not uncommon. I think Duke Ellington was playing a song and said, ‘Who wrote this?’ And they were all like, ‘You did.’ Biblically, they say it’s one of the highest callings. Sometimes I feel like it comes through me, like I can’t write fast enough.”

Another result of her writing talent is that she has also written a musical about her life. Due to Covid, it has now been reimagined into a television series. “The score is done for the musical. We can’t really do a musical until we come out of Covid so we’re going to transform it into this and hopefully still be able to maintain the rights. I can’t believe I did it. The score kind of came out as a result of that. And also like a turning point, a pinnacle in my life and another part of my development to get to where I am now and it just happened.”

And how did it happen? “I have a friend who is an amazing author. She wrote a first book late in her life. It got published in her 60s. It was called Blue Money. I was talking to her a lot; her name is Janet Capron. We spoke, and I began to realize it was a story. We began to speak about my life. My friendship with her makes me so appreciative of books and life and stories.”

Cotton holds the written word in high esteem, and believes there is a story in everything. “We can live through living, but we also live through art.”

A Different War

Help Flip the Senate

Georgia State of Mind Project

*All images courtesy of the artist’s site