Arielle admits that she likes to surround herself with artists who are better than she is. Or at least more experienced. “It’s more to try and be at the same caliber as my heroes. To be a friend of theirs, not to be a fan girl, and I realized if I wanted to play with someone of their caliber, I’d have to be there.”

At age five, this child prodigy was singing in the Peninsula Girls Choir. She was playing guitar at 10 after mastering the piano and trumpet. She lost her father at 13, entered The Musicians Institute as one of only two women in a class of 2000 at 17, was taken to the cleaners by a bad record deal at 21, and played guitar on the Nashville TV show for six years from the age of 22 to 28. Now 30, she’s lived a fuller life than most musicians who survive into their 80s.

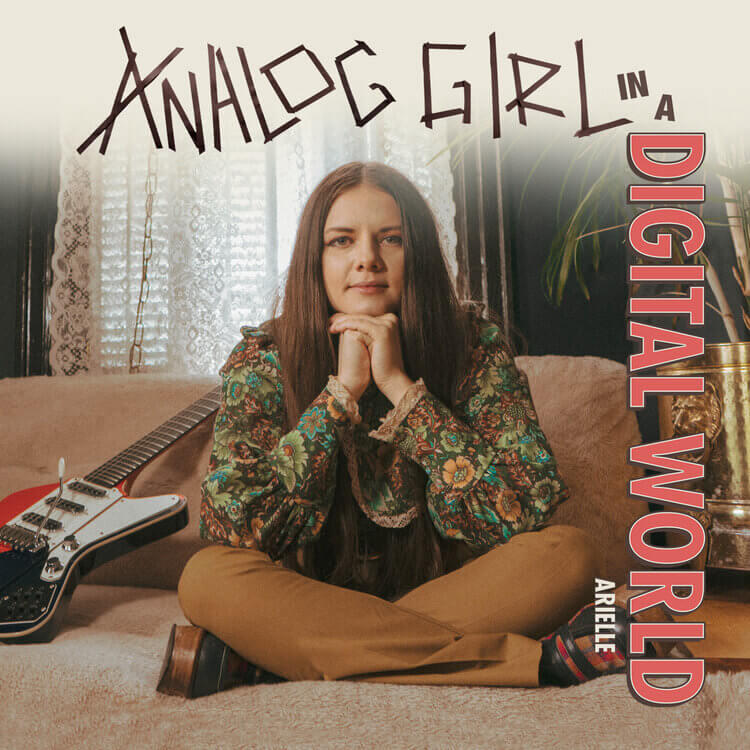

The dance card of acts she’s toured with reads like a who’s who of rock royalty of the last half century: Heart, Joan Jett, Graham Nash, Country Joe McDonald, Joe Bonamassa, Guns N’ Roses, members of Deep Purple, Billy Ray Cyrus, Eric Johnson, Gregg Allman, and Cee Lo Green. You can hear the ghosts of rock royalty from Fleetwood Mac to Lou Reed and Tom Petty throughout her sixth release, Analog Girl in Digital World. Many of her influences have passed. Nearly all released their best work before she was born.

Her favorite mentor is master guitarist and 22-time Grammy winner Vince Gill. With 26 million albums sold and 18 Country Music Association Awards in his pocket, he may just be the most unassuming artist ever inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

“I met him about four years ago when I won this contest. My friends entered me into this thing, and I got to play guitar with him and sing some music with him. It started off after we played together, we would meet for breakfast maybe once a month for a few years, and anytime I go back into Nashville, we always get together, but he’s become a mentor.

“He’s a normal person who’s had all that success, and it hasn’t gotten to him at all. I’ve worked with a lot of people, and I’ve never met anyone quite like Vince. And when you ask him how he is, he will tell you this “I’m doing pretty good playin’ less notes.” Even the way he approaches guitar is basic and humble. It’s very cool.

“He’s a centered person. He is wise, and he’ll give you his knowledge without even feeling for a second that he’s a rock star. He eats breakfast at the same place he has every morning. He talks to his fans. He shows up in his pajamas. He’s just himself no matter what happens to him.

“He’s very old school in that way, and he’s very fatherly. He’s got a couple of daughters my age. So, he’s like, ‘You remind me of my little girl.’ He’s so sweet, and we have a lot in common, and we don’t agree on everything. I remember I sent him some music. He’s like, ‘It’s not my thing, but I appreciate it.’ I’m like, ‘Thanks, Vince.’ And when I was showing him my guitar a few years back, he said that exact same thing. He said, ‘I wouldn’t play it, but I appreciate it.’ “

Vince Gill is old school, and so is Arielle. Her dad died just as Arielle was entering teens, but not before she got to hear all his records in every genre from rock and roll to opera. At 14 she would stand in line all day to get tickets to see Tom Petty and The Police’s last tour.

Even the title of her new album Analog Girl in Digital World announces that she’s honoring the past. “I’m still old school. I’m pulling from older Rush-type stuff, some of the older synths that Queen used to use in the ’80s. So, typically I don’t go past ’84 in my sounds. I think there’s some neat stuff from that sound period, but everything beyond that unless it’s a really great replica I usually pooh pooh.”

Arielle plays with sound like a painter using all the colors on her palette, at times blending her four-octave voice with the manic youthful energy of instrumental rave-ups that flash back to early Who and Lou Reed on “This Is Our Digital Intervention.” At other times, as in “Reimagine Redefine,” her voice blossoms like a flower in the first spring rain.

On “Rather Be in England” she captures the bucolic feel of early 70s British folk-rock. “Peace of Mind” is awash in youthful energy tempered with consummate guitar skills applied in an anthematic rush of a 70s styled rave-up. She boldly declares in “Digital World,” “There was a time when we lived without the internet. Things were so much better then…. I don’t want to live in the digital world….The world don’t stop for no one. The world just keeps on going.”

She may hate the digital world, but the edginess of that world fuels her muse.

“As early as I go is like probably mid-50s. I go from the ’50s to the late ’80s. but usually it ranges from as late ’60s to late ’70s. That’s where I try to stay around. Partially on this album I try to replicate The Who, Fleetwood Mac and Tom Petty. Lou Reed is definitely an inspiration to me, especially with a lot of my guitar stuff. I think he’s awesome, but I mean I’m sure he’s in there even if I don’t think about it.”

Even though her music looks back, she doesn’t think if her dad were still alive, he’d like it. “He was definitely more traditional. He loved jazz, classical and opera. So, to hear what I was doing was probably too much of a mess for him. The sounds that you are hearing are the synths that I use.”

Her guitar sound is pure testosterone often punctuated with bleeps and exclamation points that mock the digital of today. “I think what you’re referring to as digital sounds are a synth from the ’80s, a Moog – a second version of it – the first one coming out in the ’70s. They’re digital, sure, but I didn’t come out with any super modern digital technology.

“We used old vintage microphones. We recorded half of it to tape, and then half of it digitally, but we used the console, and we recorded it all live. There’s hardly any overdubs at all. So, the way we approached it was in a very old school analog way, and when I’m talking about the digital world, there are some benefits to it. There are a lot of benefits.

“I don’t feel we’ve found out where the balance is between being able to have a life and create music and also being able to utilize the technology beyond social media. I mean, every day there’s a new platform that you have to be on and have X amount of followers. People ask me sometimes when your first release was. Actually, the first one was in 2005, but then the other one was 2008. During these times, it was hard to get. There was no Spotify of course, and YouTube wasn’t a thing. So, as an up-and-coming artist, I’ve been doing this so long you still can’t track everything. I’ve done on-line because because it was harder because there weren’t the cell phone cameras we have now.”

Her record deal with Open E Entertainment in 2010 almost ended her career as a recording artist. “It was very, very, very, very difficult and very expensive. And very terrible. We had four entertainment attorneys that couldn’t get me out, and I had to hire a litigator, and this went on for two and a half years. They found a loophole in the contract in which someone filed bankruptcy, and the contract dissolved.

“So, I had to file bankruptcy to get out of it, and as a 22 ½ year-old going into L.A. bankruptcy court and having the trustees say, ‘How did you get into $500,000 worth of debt (It was problematic.) I think I had a car that I was leasing. I didn’t own anything else. So, the only (debt) I had was less than $8000 maybe plus the car, and I said to the trustee, ‘I’m a musician and I signed a bad record deal, and I don’t know how they spent the money and where. I have no control over it.’

“They don’t understand that kind of thing as you can imagine in bankruptcy court, and they threatened me and dug through everything that I had. They threatened I would go to jail if I was hiding money. It was a bad situation where for those two and a half to three years I couldn’t even perform under my own name, and I didn’t have any songs to use because that went away.

“They ended up owning the rights to my music, and then they tried to come after my guitars. It got so high up, the court eventually (said) what are you doing to this girl?’ These are people with billions, and I’m not exaggerating, billions of dollars, and they were coming after me to the point where they said, ‘All right, you just go and pay for her attorney fees.’ It was a very ugly situation.”

The music business has traditionally been known for eating its young. But at age 30 Arielle has risen above enough such challenges to fill most lifetimes. Not that it’s been easy. “It was very difficult for me. I think part of that was because I hid a lot of my feelings just being so busy all the time touring. I felt like I was consciously working on stuff and working through stuff. It wasn’t really the way I could have fun, so it really opened up Pandora’s box stuff I’d been ignoring and (dealing) with all sorts of things.

“It’s been hard, but I think hopefully I’ve gone through the worst of it. I feel better and it’s given me the opportunity to restart my life and have more meaning and be more careful about what and who I invite into my life. So, it feels more meaningful both inside and also what I give back.”

Being a child prodigy asks a lot of anyone whose talent is way more mature than the emotions it takes to handle. And it is rarely an easy invitation to success.

“You have to be challenged, and it’s very embarrassing to be the worst person in the room at first. And then it becomes humbling, and it becomes a challenge. It just seems obvious to me now, but I think it’s hard to remember the stages of learning how to do something, especially when we have of instant gratification of Amazon and social media. I feel very blessed to have been raised the way that I was.”

Analog Girl in a Digital World