On Corky Siegel’s Chamber Blues Extravaganza stream Saturday night, March 6, innovative sights and sounds were broadcast by select acts from their living room to yours. There were many highlights, and hopefully this recap will do some justice.

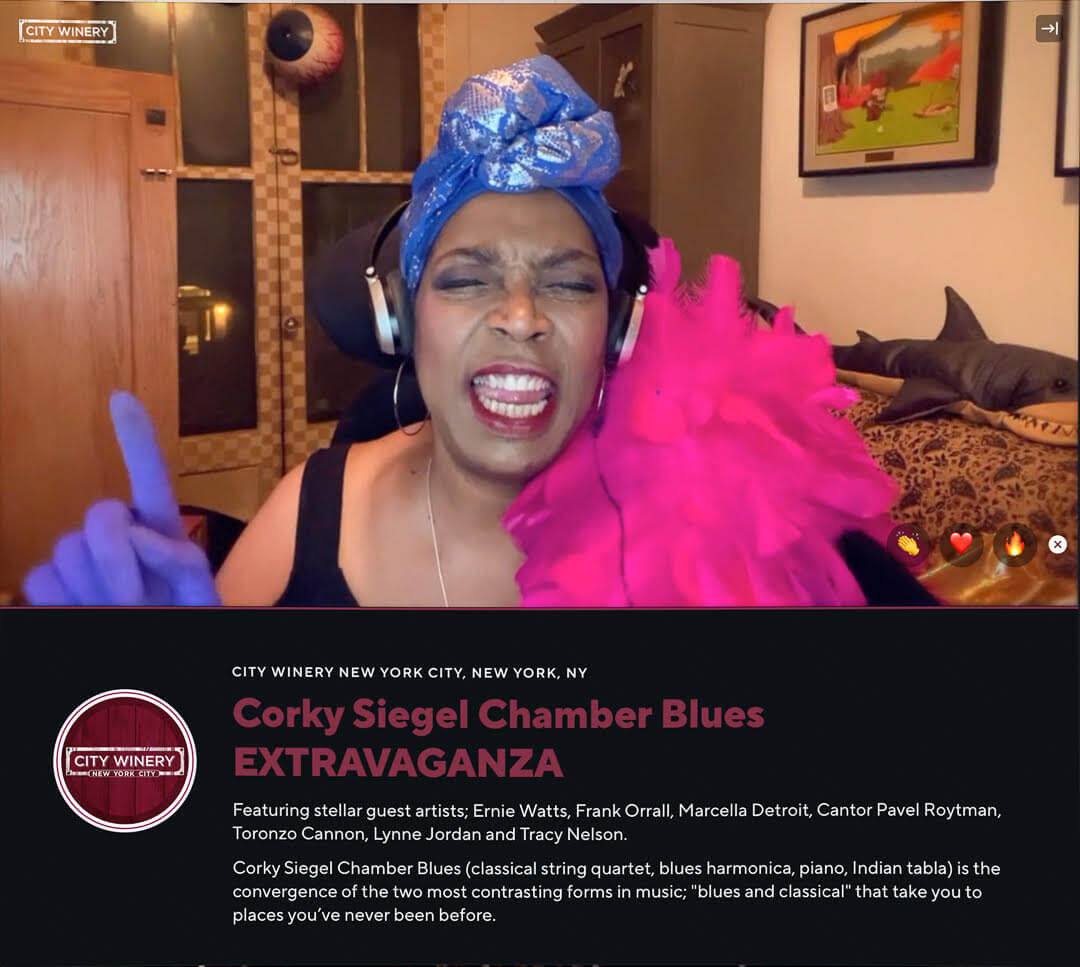

Luxuriating in a bright pink feather boa, donning purple gloves, Chicago City Winery contralto Lynne Jordan, opened. Renowned for her animated persona and burning contralto, Jordan sang from her own tiny salon. “Jump off the bridge into the San Francisco bay…”

Meanwhile, the live chat revealed die-hard Corky Siegel fans whose loyalties harkened back to the 1960s, some even recollected “sitting in the under 21 section of Quiet Knight” — a now-defunct Chicago hot spot where Siegel played weekly to crowds.

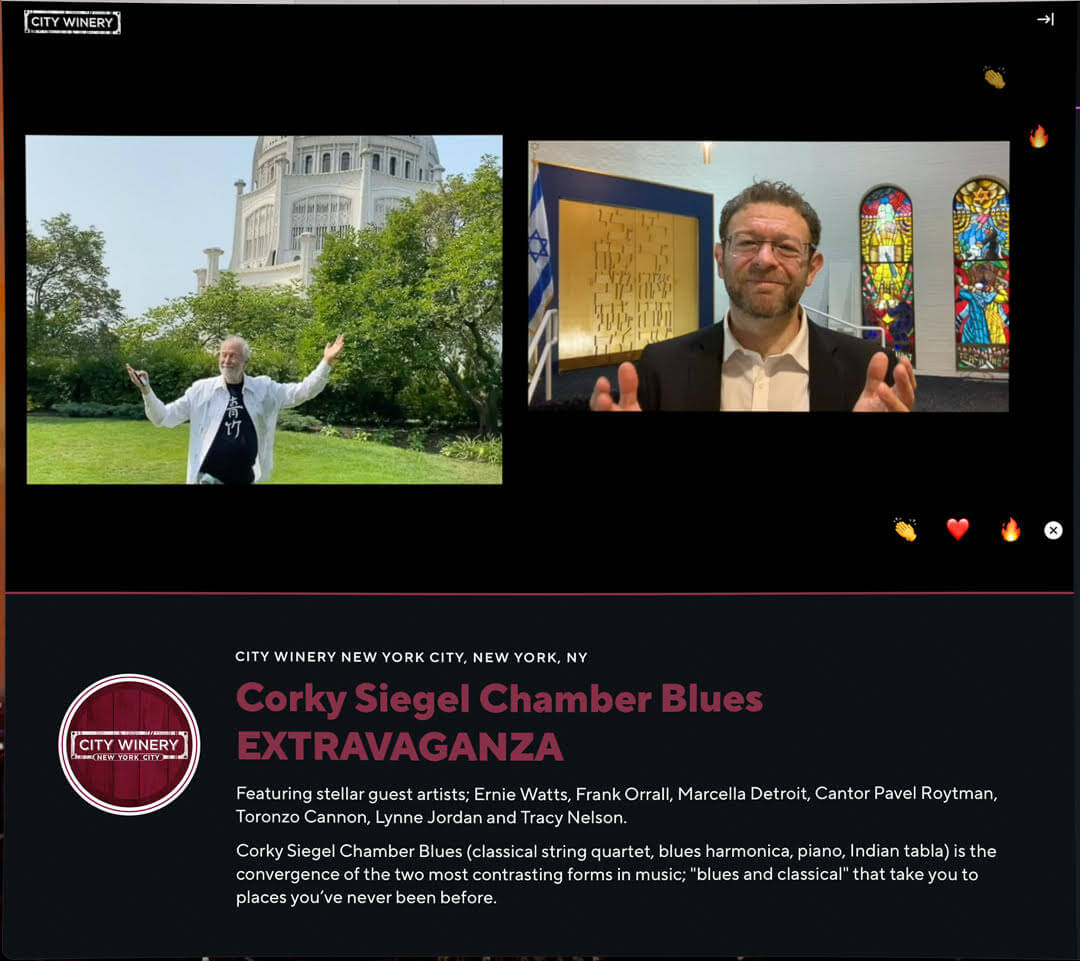

Siegel reappeared onscreen with a welcoming speech: “I’m not tethered to the stage,” he smiled. “We can meet each other wherever we are and connect,” and that comment pretty much summed up the welcoming tone of the entire concert.

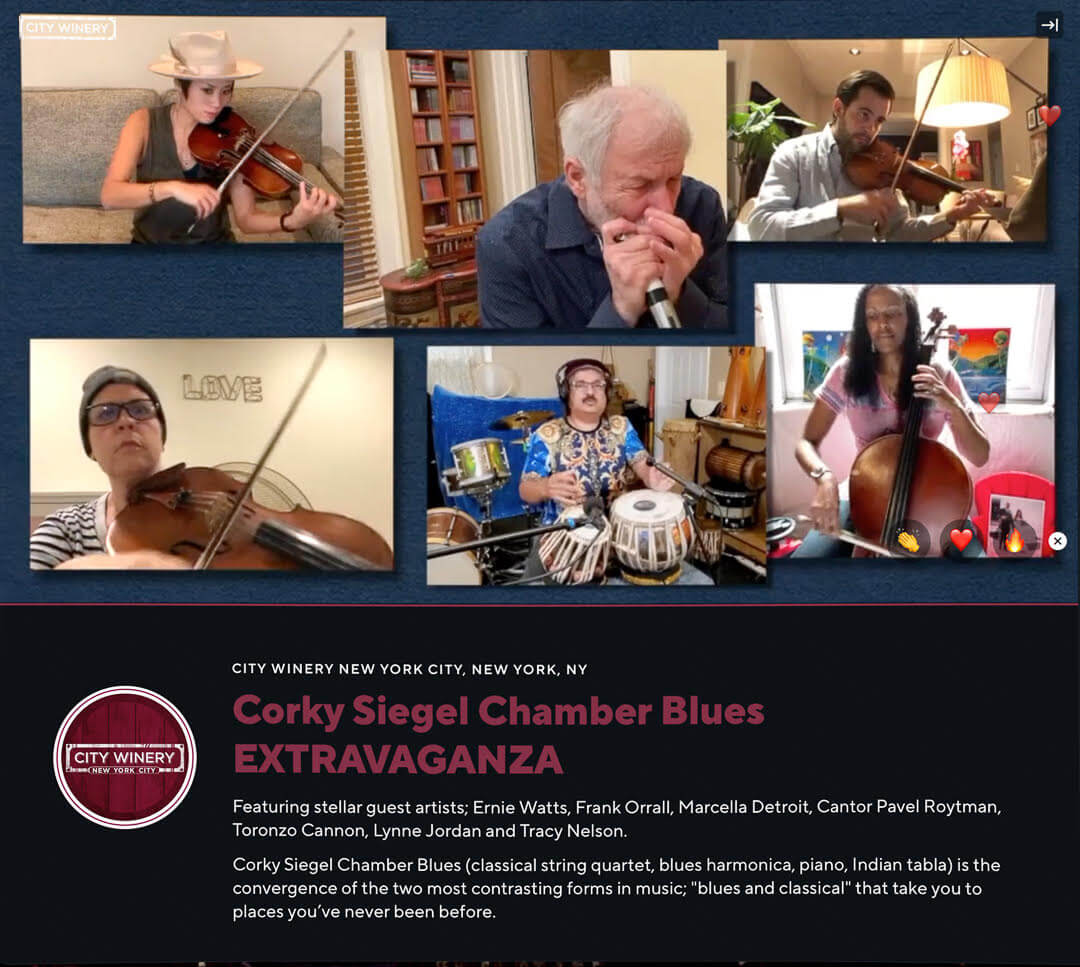

Indian Percussionist Kalyan Pathak’s beats added indescribable energy. Frank Orrall’s (Poi Dog Pondering) whispered rendition of “Little Blossoms,” while standing in an about-to-be painted room, hit the spot, as glimpses of his future home, with lush Hawaiian flora and serene beaches, flashed on the screen.

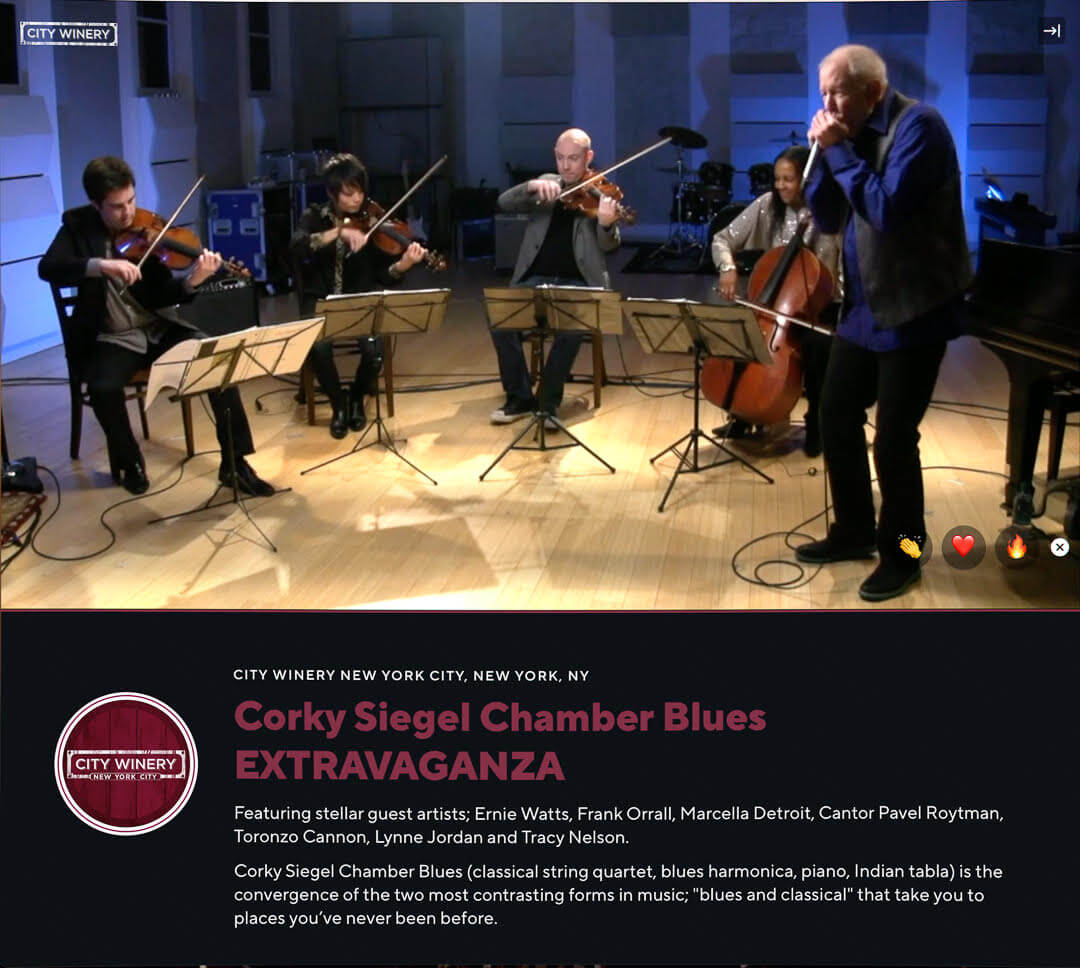

Siegel’s “Opus 17—Complementary Colors” revealed a pre-pandemic flight-of-the bumblebee-type violin solo. By the time Seigel completed his own fiery instrumental, he was kneeling on the ground, but his arms still managed to conduct that final beat.

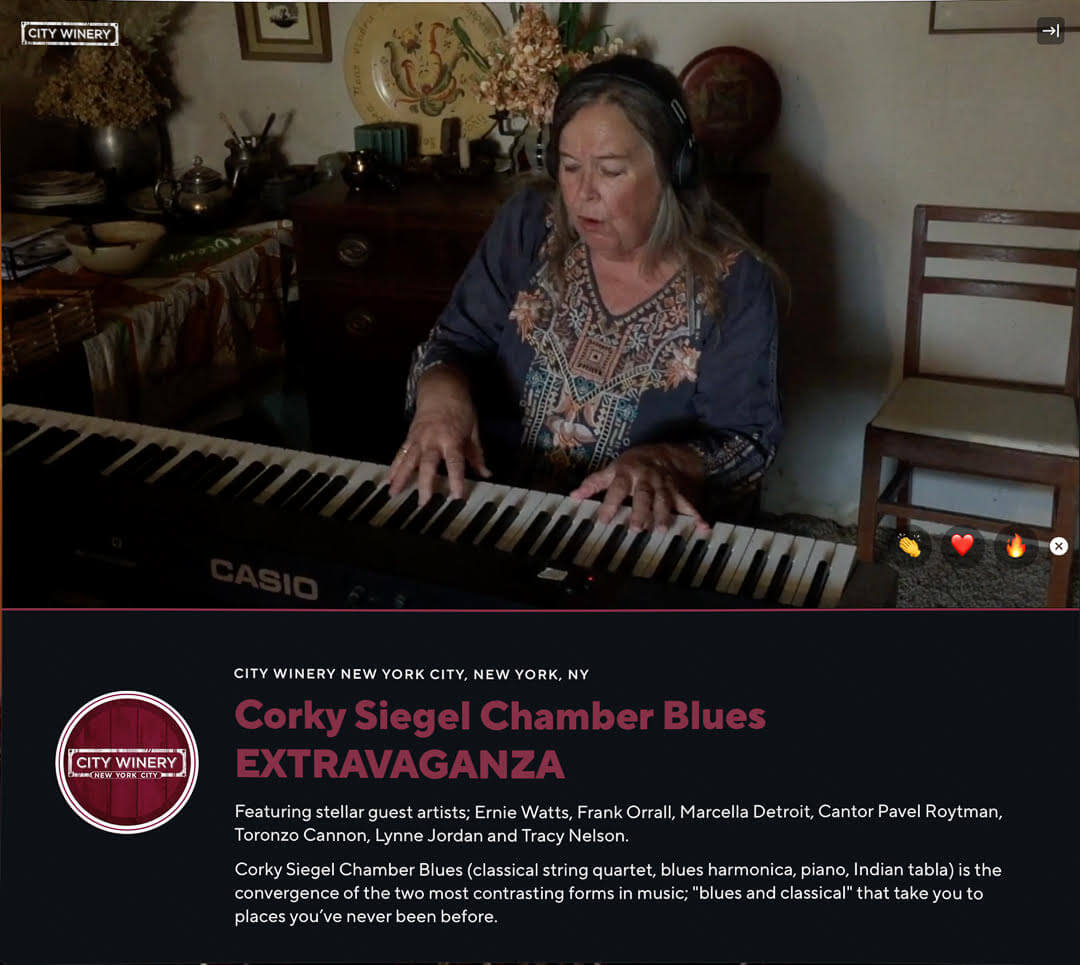

Tracy Nelson (Mother Earth) performed her warm 1968 Etta James/ Maria Muldaur covered hit “Down So Low” on an electric keyboard. And the entire Chamber Blues ensemble joined in for the infamous Siegel-Schwall classic, “Angel Food Cake,” made even more festive by a burst of choral singing. The track recently appeared in the Chamber Blues album, Different Voices.

Direct from Russia, “near Kishinev,” Cantor Pavel Roytman sang a touching rendition of “Hine Ma Tov,” as Siegel’s silhouette bent notes near the Bahai Temple.

Alligator singing sensation Toronzo Cannon performed the tongue-in-cheek “Insurance,” lamenting that “I need three stitches, doctor, all I can afford is two.”

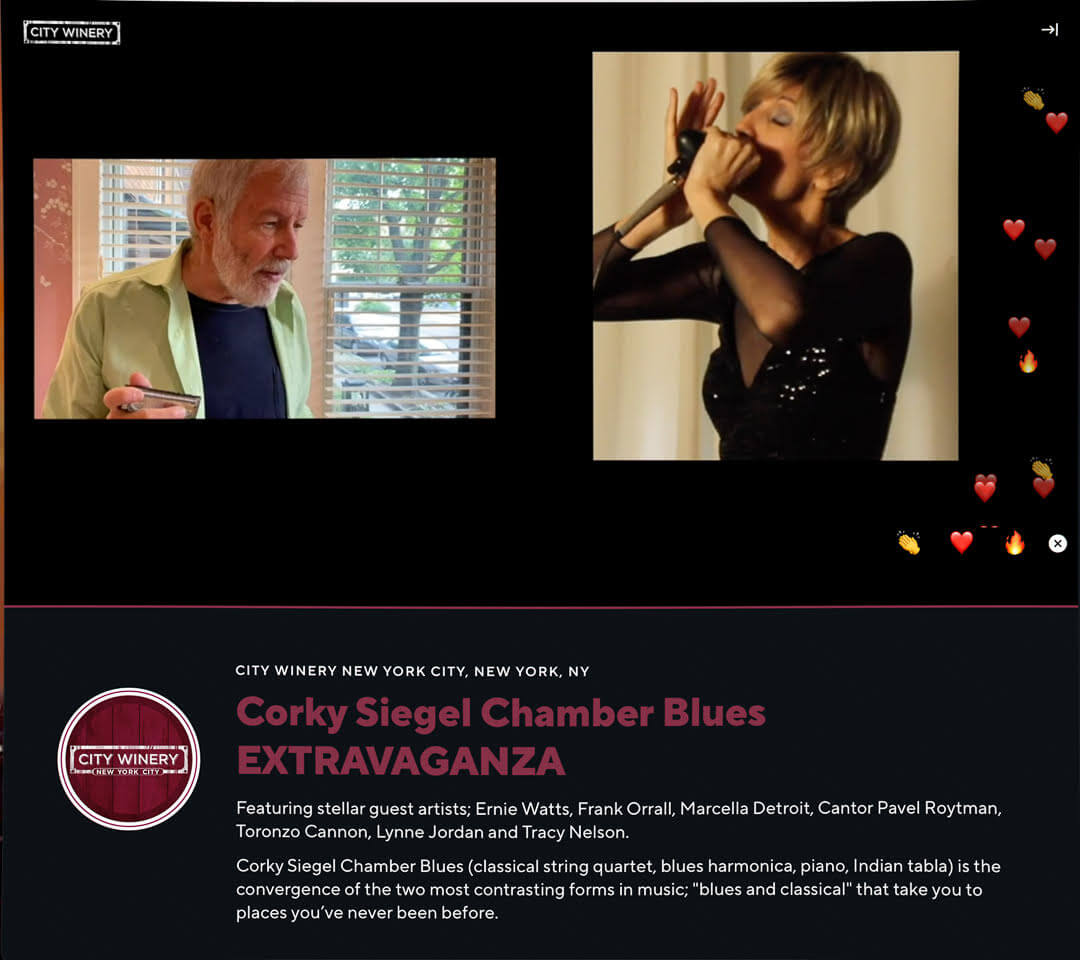

Marcy Detroit literally sparkled in her sequined gown, but even more so when seamlessly switching between opera and blues genres, finally engaging in an all-out blues harp assault with Siegel.

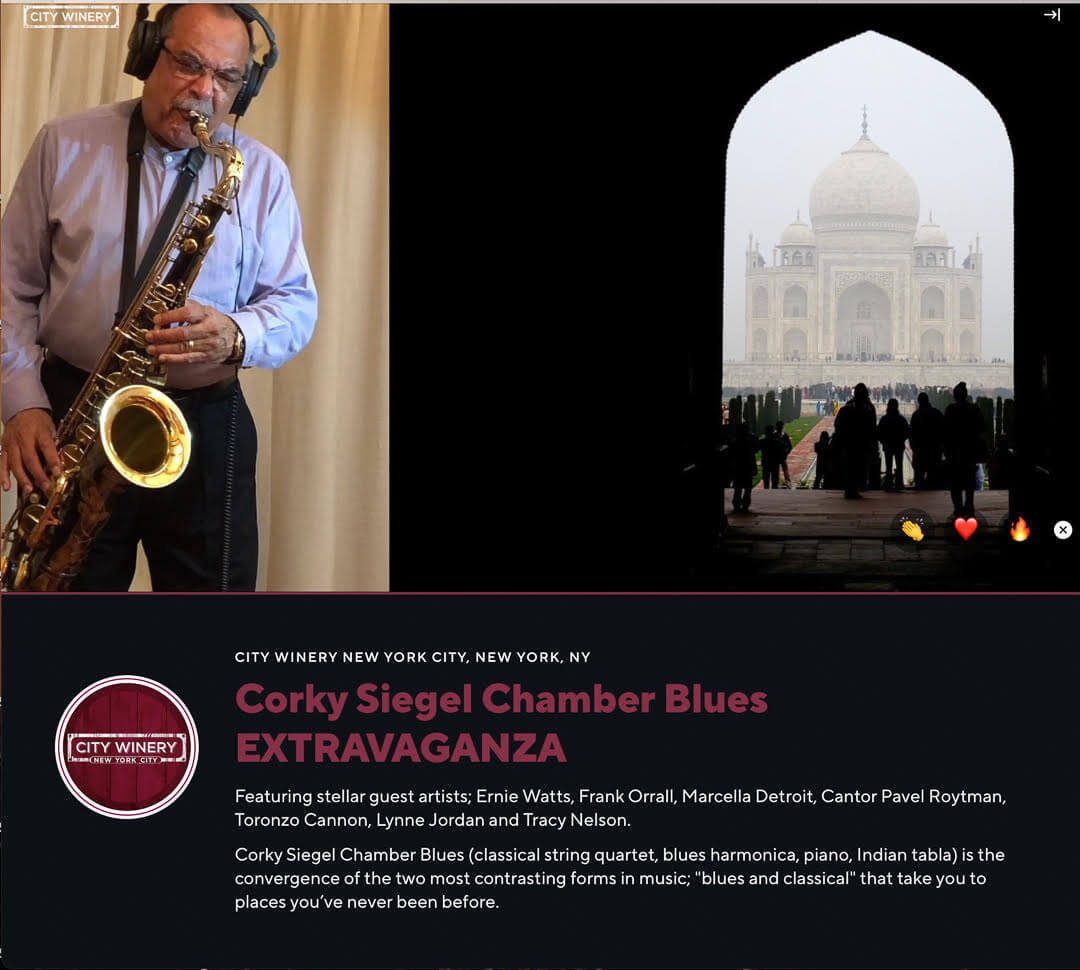

The compere ultimately headed off an acoustic piano super-jam, which culminated in twelve Chamber Blues hands adding flashy embellishments. Grammy-winning saxophonist Ernie Watts’ segue into the undulating “Oasis” was enhanced by pizzicato and accented tabla.

Another fine dimension came courtesy of blues documentarian and film director John Anderson. His keen eye for detail was evident in his intimate shots of pre-pandemic performance.

This masterfully produced concert shone a luminous light on every single act.

But if you’re wondering what Corky Siegel’s professional life was like before merging blues and classical genres, read on.

Corky Siegel formed the Siegel-Schwall band with lead guitarist Jim Schwall in 1964. Other band members were: bassist Rollo Radford, and initially, drummer Shelly Plotkin and then Sam Lay. The band performed until 1974 and then from 1987 onwards.

During this same era, another Chicago-based band, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, was also wildly popular. Both bands ultimately garnered national and international fame. During our conversation, Siegel shared recollections of this band, as well as his own early gigs and even shares his perspectives on improvising and arranging.

Lisa Torem for ABS:

One of the songs Siegel-Schwall was known for was “Corrina.” The song had a unique history, having been covered by, among others, Taj Mahal and Bob Dylan. What was unique about Siegel-Schwall’s rendition?

Corky Siegel:

That’s an easy one. One-word answer. Rollo. Rollo Radford, our bass player. The thing about Siegel-Schwall: everyone in that group was like, I’d look across the stage at Jim. No one in the world plays guitar like this guy.

And then Rollo. I look at him and say, “Man,” and of course, Shelly (Plotkin) was the drummer and later on, Sam Lay. The characters; the beauty of their souls and the unique way they, each individually, approach music. This was unbelievable to me. Not anyone of them was trying—my new phrase, to recreate the past. I was incredibly fortunate to be able to play with all of those guys.

Rollo just walked onstage and everyone was happy. He didn’t even have to do anything. His personality was so beautiful and just lit up the room. He’s still living. And he was, truly, a great being. He was never negative about anything or anyone. He would say, “Nah, no, no, no!”

Pepper’s represented a big part of the burgeoning Chicago blues scene. If you could repeat one night from that experience…

At Pepper’s, we didn’t open up for anybody. We were onstage all night. One night was the first night we played there. Johnny Pepper hired us a bass player and a drummer that we rehearsed with earlier in the day.

We started at 9:00. Howling’ Wolf sits in. Muddy Waters shows up and sits in. Otis Spann shows up and sits in. Junior Wells, Buddy Guy, Willie Dixon, Hound Dog Taylor, Otis Rush, James Cotton. One guy showed up and wanted to sit in, but it looked like he’d been drinking a lot. I said, why don’t you come back another time and someone yells, “Hey, let him sit in, that’s Little Walter.”

I didn’t even know who Little Walter was. And so, all of these people had taken us under their wings, had taken care of us; what a six-to-nine-month night! A night that lasted nine months.

The history books often cite Siegel-Schwall and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in the same breath. Were you rival bands or buddies?

We were buddies. They were out there touring and then we slipped into their slot at Big John’s. So, he (Paul Butterfield) was my big brother in that sense. The way I would put it right this second is that we were very, very close but we didn’t hang out at all.

He’d say, “Corky, let’s go out and have dinner with me at Big John’s.” We’d meet and he’d say, ‘You know, I feel like drinking. Want to go drinking somewhere with me?’ I’d say, “I’m going to go eat, because I never drink.” He went and drank and I went out to eat and that was our relationship.

He was very good to me. I remember we were at the Albert Hotel in New York. He came down and knocked on my hotel door. He said, ‘hey, I want you to listen to my new album,’ and he brought the record player down into my hotel room and he put the record on and played the whole record for me.

A couple of weeks before he died, he was in Chicago. We were on the same show, and he told me how he wasn’t going to live much longer. He had regrets about how he treated his body and how he used drugs. He was crying. I gave him a big hug, my wife and I. So, that was Paul Butterfield.

How would you describe the differences between your bands? Contrasting images, like the Beatles versus the Stones?

We were more of a jug band, a folk group. We never considered ourselves a blues band. A lot of people won’t like this, but it’s true. The Paul Butterfield band, at least Paul Butterfield, was sort of following very closely in the tracks of Little Walter.

Whereas, Siegel-Schwall, for me, I wasn’t following anyone’s tracks. I wish I could be Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters, but after thirty-seconds of trying, I realized it wasn’t going to work, so I just went with whatever came out.

People would tell me, oh, you took the blues and you’re doing such original stuff. Well, no, I was just trying to do whatever I could do (laughs). However, it came out, is however it came out. We were not trying to copy, in fact, we were doing things that other contemporaries of ours did not like. They didn’t like the way we played, but the blues masters, loved the way we played and told us so.

Howlin’ Wolf used to come to the north side to sit in with us—I mean, what band did Howlin’ Wolf sit in with in Chicago? He took us on the road. He loved Siegel-Schwall. We were young kids. I was just learning to play. Jim was pretty good from the start. I was just learning how to play and struggling with the whole thing. There was just something they loved about the way we were doing things.

Can you comment on the evolution of your material over the years? Especially, in regards to lyric/theme?

In the original days, our lyrics were a lot of standard blues-type things that were sort of mean and not nice to women. A lot of the material was like that. It was totally self—centered with a good helping of naivete and another good helping of lack-of-compassion and certainly a lack of understanding. I don’t think I began to mature as a human being until my late thirties. So, the lyrics developed as I went along.

Eventually, you found your way into composing classically-oriented music. (Siegel’s classical compositions, such as “The Symphonic Blues No. 7” are internationally acclaimed.)

My first composition, believe it or not, was in 1975. I actually wrote symphonic sonatas for the San Francisco Symphony with Arthur Fiedler, the conductor you saw in the Culture Clash video. (Siegel directed me to an early video prior to our interview).

It was a twenty-minute long, three-song piece that I performed in front of six thousand people at the Civic Auditorium with the San Francisco Symphony and Arthur Fiedler. I wrote the piece, having never written anything before. I was asked to write it for the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Symphony and Arthur Fiedler.

I told them all, ‘I’ve never written anything before. I don’t know how to do it.’ They said, ‘Oh, come on, you can do it.’ And I figured, okay, I don’t have to live in San Francisco. I’ll go ahead and write it and we’ll see what happens.

So, it turns out that from that piece I got another commission from the Nashville Symphony and the Grant Park Symphony—I wrote two for the Grant Park Symphony. I stopped accepting the commissions because it was too much work. And then, there was the concert in Lancaster, Pennyslvania, with Lancaster Symphony Orchestra.

The maestro, Stephen Gunzenhauser, asked me to write a piece and I said no. He asked me again and again and again and again and I turned him down year after year. And finally, I wrote a piece for him in 2007. It was such a major success; I played it all over the world. It got rave reviews and other composers and opera stars just loved the pieces, so the following year he asked me to write another piece; all the artistic directors were saying, ‘No one else in the world is writing music like yours.’

And we all knew the reason why—it’s because I had no idea what the heck I was doing. Nevertheless, they loved the pieces and always wanted me to write more. I kept turning commissions down, one after another. And finally, in 2018 or 2019, I agreed to do another piece which we played about a year-and-a half ago in Austria and in Lancaster.

The 2007 piece I especially love. It’s never been recorded, nor has the newer piece. And I’ve been really trying to get it recorded. But the pieces are based on: “Opus 12 Chamber Blues” and then sort of a loose version of “Opus 19.”

What I do when I work on a symphonic work based on Chamber Blues, the idea is that I don’t have to start from scratch, but I can take all of the things that inspired me, in writing the Chamber Blues piece and then I can expand on that and try different things and then that becomes the symphonic piece.

So, “Symphony no. 6” includes three movements, which is “Opus 12,” “Opus 19” and “Opus 8.” I really love the piece so I think I’m going to record it some time.

Can you walk us through the process of writing an arrangement for harmonica?

First of all, I write things that I know I can play. And when I’m writing something that I can’t play, I don’t play there. I write in a way that I can not only play it, and be able to improvise and not lose my place because I write in all kinds of cues for myself, so I know when I hear the trumpet, it’s time for me to hop in and then, I just improvise.

Sometimes, I will write a little something, just to anchor something down, but mostly, I’d say 98 percent of the time, my parts are improvised.

The way I play tends to be not with notes or phrases but with expression—little bursts of expression. A particular phrase may be made out of six notes but I experience it as an expression and a variation of that phrase is a variation of that expression.

So, when I’m playing, you know, with the harmonica you move it to the right, you move it to the left. You breathe in, you breathe out. Each phrase has its own position so I don’t think of it as a musical thing, but more of a physical thing; I’m expressing myself physically by playing these patterns.

I’m expressing myself through a physical pattern so any improvisation is all the same; it’s basically a bag of tricks—all your phrases, all your melodic ideas, everything’s in the bag and you can pull them out. You can’t make a mistake, you can pull out anything you want.

Your artistic integrity is working and you’re just trying to put things in a way that creates joy for yourself. The only difference between me and other musicians is that I’m more doing it through the patterns than I am through intellectual knowledge of the phrases and the notes.

When you’re improvising, ideally you want to stay in the moment. It’s very hard to not stay in the moment. Everything is going by so quick but one of the things that can completely destroy or distract you is: ‘hey, that was pretty good’ or ‘whoops, I made a mistake’ or ‘gee, I wonder how they’re liking this.’ Death. So, my focus is very meditative in allowing myself to stay in the moment. So, I like to stay in the moment and do it and not have any judgment.

The judgment, and I talk about this in my book, ‘Let Your Music Soar: The Emotional Connection,’ but judgment process is useless and totally destructive. It’s the anthesis of what anybody should be doing in the arts. And people might say, how can you make decisions if you don’t use the judgment process?

Well, I look at the judgment process as balancing pros and cons. This is good; this isn’t good, instead of making choices intuitively where you just hold it up and say, that feels nice. And if it doesn’t feel nice, then you move on to something else, but you never spend time judging one thing or another, whether it’s good or bad. The judgment process is way too slow. The intuitive process, where you just go with how it feels; you stay in that state and that’s what allows you to improvise and then stay in the moment.

Who have been your blues harp heroes?

Everybody. At first, I listened to Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters and Jimmy Reed and that was it. And of course, Little Walter was on one of those records. And I listened to everybody who played at Big John’s or Mother Blues and Pepper’s with Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Otis Span, James Cotton. I didn’t study them, I just let them carry me away.

My objective wasn’t to learn because I knew I was learning just by being there but I wasn’t trying to get the licks.

City Winery Chicago

Corky Siegel’s Chamber Blues

*All images: © Phil Solomonson / Philamonjaro Studio