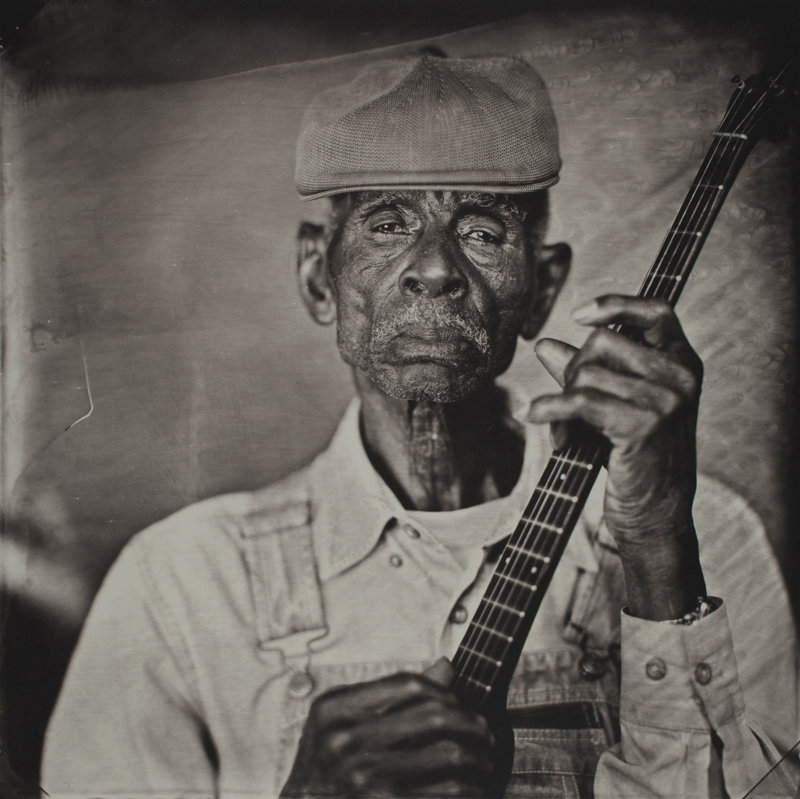

John Dee Holeman was the epitome of what it meant to be a Piedmont bluesman in the tradition of pioneers such as Blind Boy Fuller. He had a great saying about how he learned to play the blues: “I caught it from my cousin who caught it from his uncle.” That uncle he speaks of played with the masterful Blind Boy Fuller in the early twentieth century.

Holeman was born in Hillsborough, North Carolina on April 4th, 1929. He passed away the morning of April 30th, 2021 of natural causes at his home in Hillsborough.

“I was born in 1929,” he would say in his lilting, soft-spoken manner. “My father was Willy Holeman, and my mother was born Annie Obie near Roxboro, N.C. Her daddy moved to Hillsborough and ran a flour mill. James Obie was my uncle; there are still Obies in Hillsborough. I lived on the Sam Latta place at first – he was the High Sheriff. There were three sisters and one brother. My parents are planted in the cemetery of Obie’s Chapel Church in Person County.

“In about 1935, we moved to a 100-acre farm on Gray Road in northern Orange County. We would walk four miles to the store at Timberlake to get us some candy. We could play on Saturday or Sunday, you know, fix a swing in a tree, swing in a tire and things like that. One time I took a fender off a Model T Ford, got on a bank, put water on the bank, and slid right down to the bottom! I completed the fourth grade, then stopped; we weren’t compelled to attend then. I cut short my education because Daddy needed me to farm. I had to do what my Daddy said. I missed my education, but I’ve made a living so far.”

When he was 14, he bought a new Sears Silvertone guitar for $15. “I thought I had something!” he said. His uncle and cousin taught him a few chords. “I listened to 78s like ‘Step It Up and Go’ by Blind Boy Fuller, the Grand Ole Opry, and heard others play at pig-picking parties. I was good for catching on. My guitar kept me company when I tended to tobacco in the barn so I wouldn’t go to sleep. You had to control the tobacco as it cured – you ran one heat to get the green out, then another to dry it out for cigarettes.”

With the farm struggling, he moved to Durham in 1954. “The government took over the farming and gave you an allotment of how much you could raise,” Holeman recalled. “Before that we raised as much as we could handle. If you went over the allotment at harvest time, they’d make you cut it down. In 1954, I got $200 for my portion of tobacco for the whole year. I went to the Liggett and Myers Tobacco Company for work. You could get a three-room ‘shotgun’ house for $6 a week. I also operated heavy equipment, like hauling dirt.”

It was his skill as a guitarist that first set him apart. In Durham, he got to play with musicians who had learned first-hand from such bluesmen as Brownie McGhee, Sonny Terry and Reverend Gary Davis. In recent years, he had been a regular at Durham’s summer Warehouse Blues Concert Series at the site of the old L&M factories and warehouses where he once worked.

In addition to playing, he worked construction as well as at the tobacco warehouses.

The great University of North Carolina folklorist Glenn Hinson was the first to bring Holeman’s music to wider public attention in the late 1970s. Then, in the 1980s, John Dee finally began touring, playing the National Folk Festival at Wolf Trap in Virginia, Carnegie Hall in New York City, and abroad as part of the wide-ranging musical revues staged by the government’s now-defunct United States Information Agency. Those tours took John Dee to more than forty countries around the world. In 1988, he was awarded a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, still proud of the certificate signed and given to him by then-President Ronald Reagan.

In 1994, Holeman was presented with the North Carolina Folk Heritage Award. A song Holeman wrote, “Chapel Hill Boogie,” was featured on the 2007 Grammy Award–nominated album 10 Days Out: Blues From the Backroads, recorded by Kenny Wayne Shepherd.

Music Maker Relief Foundation has released four albums, most recently 2019’s Last Pair of Shoes, booked countless performances in the U.S. and overseas, and provided emergency assistance when Mr. Holeman needed to relocate. Holeman has recorded on the Music Maker label, backed by such artists as Taj Mahal and Cool John Ferguson. Taj Mahal said, “When John Dee and I sat down and played together the experience was like coming full circle back to my roots! His music took me straight back to a gentleman named Lynwood Perry in Springfield, Massachusetts, the only person I ever learned to play guitar from. As it turns out, Lynwood was also from Durham, North Carolina. It was like meeting up with an old friend! John Dee Holeman is a carrier of the southeast guitar tradition.”