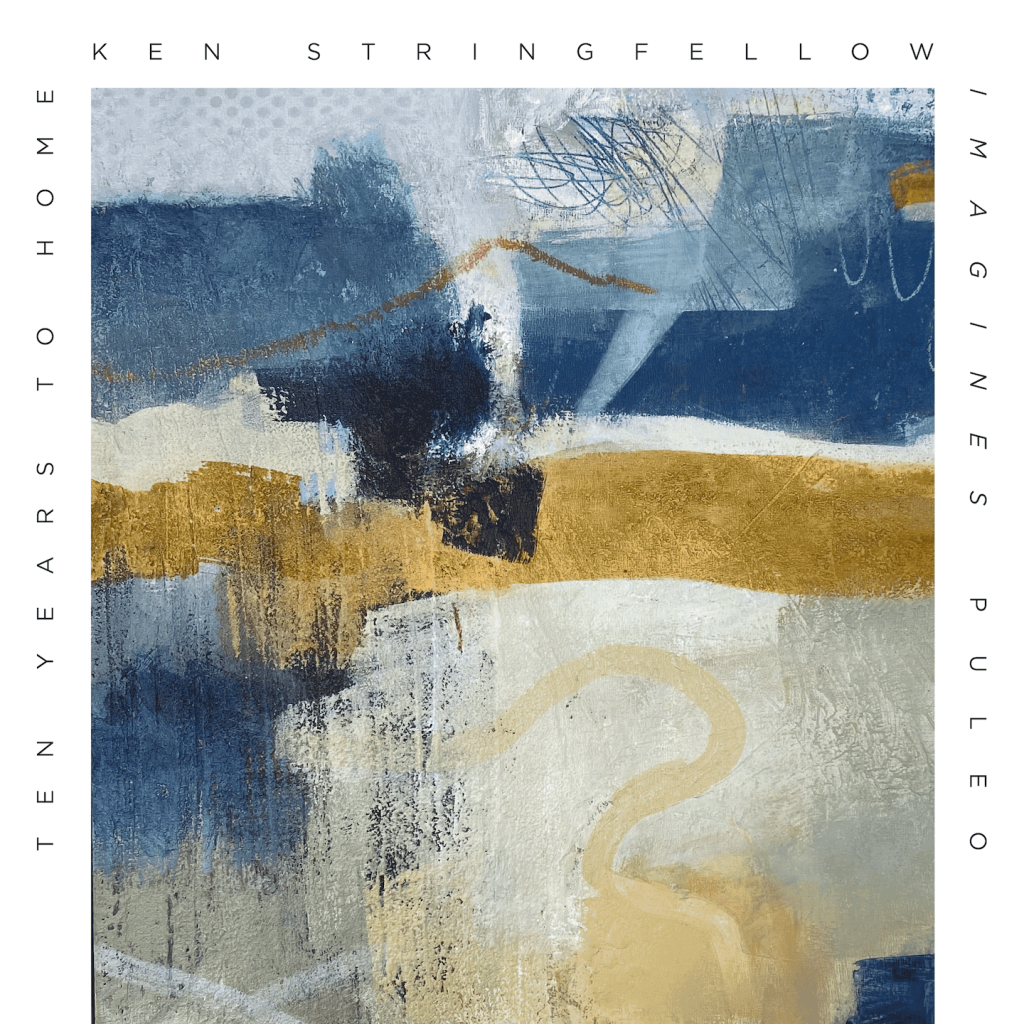

“I got to do my favorite thing today,” Lyricist, track coach and non-fiction author Joe Puleo begins our conversation. “I got to go to a track and I got to coach really good runners. There’s a local boy that I started helping with and he’s training for the high school national championships in Oregon. And it was great; it’s my happy place.” Singer-songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, and producer Ken Stringfellow enters the Zoom meeting: “I have to say, everything is hitting me at once. I have our first show in two years going on sale today for my band. All this crazy stuff is going on. So here’s yet another amazing thing happening.” The other thing he’s referring to, besides his longtime band The Posies, is the release of Ten Years To Home: Ken Stringfellow Imagines Puleo — in case you were wondering about these two unlikely collaborators.

The career paths of Puleo and Stringfellow seem poles apart. One is a nationally ranked triathlete who’s been coaching track for over 30 years, and the other an internationally esteemed musician who’s been a power-pop touchstone for equally as long. In addition to co-founding The Posies, Stringfellow spent a decade touring and recording with R.E.M. and was instrumental in the reformation of cult heroes Big Star. He played with original members Alex Chilton and Jody Stephens, and Posies’ Jon Auer, from their reunion in 1993 to Chilton’s death in 2010. Other varied artists with whom he’s collaborated with include Patti Smith, Neil Young, John Paul Jones, Thom Yorke, Wilco, etc.

Inspired by the courageous spirit of track and field national champion Gabriele Grunewald who passed from cancer in 2019, Puleo wrote the song “Not Today.” The voiceover before the song is a quote from Grunewald: “I hope people see that you can still make something beautiful and powerful out of a bad situation.” The song’s title refers to when Gabriele’s husband relayed the message from the doctor that her vitals were indicating she would die soon. She replied, “Not Today.” Initially, it was the only song Puleo had planned on contributing. But when Stringfellow heard the chords and melodies of the song as fast as he read the lyrics for the first time — and after Puleo cried upon hearing the final chorus — talk of sending more songs back and forth digitally materialized into an EP. Posies drummer Frankie Siragusa added percussion to four songs from his studio in LA.

Listen to The Posies and study Puleo’s lyrics, and you’ll find one unequivocal thread runs through both of these creatives: respect for the written word and its ability to tap into the human condition. With Stringfellow’s earnest music as the conduit through which Puleo’s personal and poetic words irradiate, Ten Years To Home: Ken Stringfellow Imagines Puleo is the carefully calculated sonic space between fear and faith, bedlam and bright side.

ABS: How do you guys relate this album to your own lives? In particular, how has 2020 affected you?

Ken Stringfellow: I have something to say on that subject, having just written my band’s album already — we were working on my band’s still not yet released album in 2019. I kind of put out a lot of my own songwriter vibes. I’d put out what I wanted to say and made my big statements, in a sense. And then 2020 happens, and things change radically for everyone, myself included. I’d put up the word that I was interested in doing even more studio work than I usually do, which I usually fit it in around the tours. This opportunity to work with Joe came up, and basically, he provides the subject matter. My job is to create all the music and execute that music. Not just write it, but perform it, sing it, mix it, do all this stuff.

In a way you could say that the direction or the mood of the songs were created by the lyrics. But I have to say that all of the emotion that 2020 brought up, with the uncertainty and the trauma of all the people dying and George Floyd — none of that is in the lyrical content of these songs, but those emotions have nowhere else to go. The music is even more intense and emotional, I think, because of these things. Not everything in art and music is linear; the songs aren’t about 2020, but they also are. That intensity is like a flame accelerant on the emotionality of the music.

ABS: Joe, can you talk about hearing your own words set to Ken’s signature sound?

Joe: Ken had mentioned George Floyd. I read that piece you did, where you sort of did a through line with Billie Holiday and George Floyd. So what’s fascinating to me, Lauren, is I had no idea who Harry Anslinger was until I read The Recovering by Leslie Jamison. She features prominently his policies in the book. So when I read your article, I was like, ‘Weird that I’ve never heard of this guy, and then twice.’ So, there’s another connection. The mutual friend who put Ken and I together is really good friends with Leslie Jamison. To get to your question: oh, it was ridiculously awesome.

I knew Ken founded The Posies. I didn’t know some of the other bands besides R.E.M. and Big Star that he played with. So when I found his connections, big picture, I was like, “Oh my gosh, this is crazy.” And then when I heard “Not Today” about Gabe Grunewald, I heard this soaring chorus at the end. The chorus is great, but at the end Ken just really digs in. It’s absolutely stunningly beautiful. And I cried.

ABS: I cried, too. Powerful lyrics need a strong melody to adequately interpret and mirror that emotion. “Not Today” achieves that. Learning how quickly you put that together is kind of fascinating. Like a writer not jotting their thoughts down in time, did you ever feel like you might lose that — or was it always going to be what it became?

Joe: When Gabriele died, I had a friend who worked on the documentary that Brooks, the running company, produced. It was her last national meet, and she had a huge scar on her chest from surgery. She was going through chemo. There was no chance she could do well, and she did it. I bumped into my buddy and asked, “What’s she like?” And he’s like, ‘She’s the best human being any of us will ever meet.”

There was a scene in 2014 where she won the national championships in the Indoor 3000 and a rival coach tried to get her disqualified, because she beat the Nike sponsored athletes. They were going to take her victory away from her, but they ended up reversing it and giving it back to her. When she died, The National dedicated one of their songs to her at a concert. That was her leading edge, the bravery. My son’s name is Gabe, and he runs the same events that she ran. Our mutual friend introducing me to Ken who was coming off tour, the energies — it was a perfect storm to do this.

ABS: In terms of the writing process, how does it compare to other works you’ve written?

Joe: I’ve never written a song in my life. I still don’t know how to write a song. I was working on a manuscript for a novel. I’ve written a couple of non-fiction books on running, but I was writing a manuscript for a novel. They tell you to just keep writing; write all the time. So I would shut the computer down and just doodle. And then I would get this notebook and I would write in it. I’m working on an LP with a friend from another band, and I brought the songs to him before we started doing this.

And he said, “I hate when people do this because you expect me to turn your writing into good music because I’m a musician, and I don’t want that to get in the way of our friendship.” We did one for me as a favor. He did the second one because the first one was mildly intriguing. And when he did the third one, he said, “Dude, we’re doing an album. This is ridiculous. How do you do this?” I had some songs left over from that session that we weren’t working on that Ken and I worked on. And that’s how the EPs were formed, but I have not written a song since I wrote those songs. And I had never written a song before then. And when I was writing, I didn’t know I was writing a song. Ken can tell you when he saw him, he probably didn’t think they were songs either.

Ken: I opened the word document and started hearing the music instantly. The song wrote itself as fast as possible. Getting to some of the longer lines that didn’t fit in the same way the next time around, in a different part of the song, the only way to really deliver that is in a Dylanesque, half-talking kind of way. That first opening chord was instant. I was hearing it as fast as I could play it. I grabbed my guitar and the song wrote itself in the exact amount of time it took to read the lyrics for the first time when I opened up the document for the first time.

Musicians are a certain kind of people who write music and have an antenna that picks up on things. I’ve been chosen to be the midwife, shall we say, of a certain necessary musical feeling. We just know that we’re supposed to birth this thing and do the best we can and give it the proper respect.

ABS: What was your process of composing the music for the rest of the songs? Did it fall into place the same way?

Ken: Totally. I was on tour in the U.S. — I live in France. I was on tour in the U.S. until I played my last show in March. I still had plans to be on tour for another weekend, and SXSW was where it was going to end the following weekend. I had this very strange situation at the beginning of the tour, because I knew I was going to be in the states for a month. My passport was expiring at the end of 2020. I was supposed to go to Algeria at some point in 2020, and you need six months validity and your passport. So I thought since I’m going to be in the states I’ll just get my passport renewed right now and take care of that, because I won’t need it for the next month.

Suddenly it was obvious that I needed to get back to France soon. Things were going to shut down.I got a call saying my passport was ready. I woke up at my hotel in Houston having played the show the day before, with a voice in my head saying, ‘Go now.” I booked the plane to LA. The flight was leaving in 90 minutes. I drove like a Texan to the airport, dumped the car, flew to LA. Their office had already closed. My assistant drove all the way out to LAX to hand me the passport. I booked a flight to France that afternoon and got on a plane. The president announced the closure of the borders. The next day at noon, my flight landed at 11. Trains were already stopped. My wife had to send a private car and driver to pick me up and hustle me home. It was all very dramatic.

I put out this call on Facebook saying, “Hey, I’ve got my home studio in France. I’m ready to work. Let’s do things. And amazingly enough, I got all this work. Every day I had a project. I basically didn’t even have time to look at the thing until the day it was scheduled for me to work on that thing. I can hear the whole thing beginning to end. Don’t even have to think about what chords to use. I can hear, what key it’s in. And then I would make a demo and then send that off to Frankie so that then I could play all the stuff on top of those drums. When we were doing the other songs, it was the same deal. I just had that day and that first day, those other four songs. That afternoon they were done. It’s super weird. For my own songs, I try and keep it fresh. If something is taking too long, that’s usually a sign that maybe you’re pushing something that doesn’t really want to be pushed. It doesn’t have enough momentum to really carry on. The genesis of it is usually in that first day that I’m working on while it’s fresh and I’m in that spiritual, intellectual, emotional zone.

I have to stay in there, otherwise it’s out of context later. These tunes — it’s like a Google search. How do they do 54 million things in a second and a half. It was so fast that it kind of defies all logic. I just had an afternoon for that. I had to write them and then make a basic demo so that I could send that off to Frankie. So that the next time I’d have drums and I could just carry on with the recording. But really it was like lightning fast bolts from the blue.

ABS: Are there favorites?

Joe: It goes back and forth. I had a contest with my house painter, who’s a musician, and we were talking about songwriting and he said, “Yeah, I haven’t really written a song in a while.” And I said, “Me neither, why don’t we write songs?” I said, “If we can write a bunch of songs before you finish painting, we’ll call the EP House Painting Chronicles. They became the lyrics that became “Overcoming Gravity.” But I think my favorites are the ones that I wrote for my children, because my children just adore the fact that I love them that much and would write a song. Ken just crushes the chorus. You know why the title is Ten Years? The home is my Odyssey. But the cool part is that, because there’s only five songs, you can fall in love with each of them. All of them have some — no pun intended — gravity and resonance.

ABS: Can you elaborate on “My Odyssey”?

Joe: I got to flex my mythology chops a little bit. So James Joyce wrote Ulysses, which is considered like his version of the Odyssey, but there’s another Greek Odyssey. It was written by Nikos Kazantzakis who wrote Zorba the Greek. I read the Odyssey to my son when he was an infant. Clearly, that’s ludicrous. When I finished the book, I realized it’s about a father and son relationship. It’s not really about this man fighting a war. It’s literally his love for his son, and getting home to see his wife and his son. That resonated with me. I threw in some stuff about the Cyclops. I was always fascinated by how tells the Cyclops his name is Nobody. So when they escape, the other Cyclopes ask, ‘Who’s hurting you?’ And he yells, “Nobody!”

ABS: Ken, have you thought about incorporating some of these songs into a solo set sometime?

Ken: I did do “Not Today” at my last online show. Nothing I do is truly a work for hire. You could make that argument; people pay me to do what I do. I do things professionally, but it’s really more than that. I mean really. I mean, I put a level of commitment into everything I do. I may not be the greatest musician in the world or the greatest mixer or whatever. I really can’t imagine somebody questioning my commitment. I really put heart and soul to an extreme degree. It’s got to have that impact, and that impact can only come from sincerity. There are things you can do to trick people’s emotions — a big modulation, all the things that people who make hit songs for a living do. But that’s not really my way of doing things.

I did a movie a couple of years ago, and I didn’t really understand anything about acting. My concept of acting was, you put on the costume, you do your research, and change your accent and suddenly your Sherlock Holmes. Actually that’s not it at all; that has nothing to do with the art of acting. I didn’t know, but you basically pull up real emotions from things that really happened to you and reproduce them based on certain aspects of the character that you’re playing.

So when you’re crying, you’re not pretending to cry. You find something in you that will make you cry. It’s total emotional nudity as, as someone has pointed out. But somebody said that acting is getting naked in front of strangers. And that’s from an emotional point of view, of course. I can’t just do some things that I think will be convincing when I’m writing music, even for someone else. I’m opening myself to what will help these songs become songs. I would say that those intensities are mine. That’s what I brought to the picture. To give fuel to those words — which are also intense — it’s one plus one equals three, ideally.

With all the terrible things going on in 2020, we all had to try and make the best and take away something positive from the situation. I’ve always been interested in doing more studio work and more music production. I’ve always had my hand in some kind of studio somewhere. 2020, when I did nothing but records back to back — my personal level of mixing and engineering and all those technical things went up on many levels.

The work I was doing pre-pandemic and now is night and day. When I first played “The Strongest Man,” the first mix I did was like, “Holy crap. This sounds amazing.” All those songs together — it sounds like it was meant to be; it doesn’t sound like it could have possibly been as quick as it was. But if I had done this same EP a year ago I wouldn’t have had this technical skill to make it as good as that as I was able to now. At the same time, the journey of making the EP pushed my skills along further. So there were the results and also the learning process, continuing. I benefited from the situation that otherwise, globally, was a bummer.

ABS: I’ve heard that from other artists who have said, while they got better technically, they just missed the live energy and they need that back. You know? So now you’ll have both coming up soon.

Ken: I have to say, I love working in the studio. And of course it’s even more fun when I got better at it, because before I was kind of holding on for dear life. But now I feel so comfortable in the studio. That gives you more confidence, which makes the whole thing more fun.

Joe: As you were talking, Ken, I was thinking about it. Within the music industry, you’ve played many different roles, right? You’ve written the songs, you’ve played guitars, you’ve played piano, you’re now mixing.

I started with coaching Olympic Trials qualifiers in the marathon. Then I went to top five in the U.S. and the javelin. And now I have a 400-meter runner, who’s at the Olympic Trials in both Kenya and the U.S. And it’s the same sport, right? You’re doing music, but we’re touching on totally different skill sets by coaching in those different areas, and it just enhances your overall talent in that field. There are a lot of things that I would have never chosen to take but came out of circumstance. I have to learn that I have to be my best at it, to offer that to the athletes that want me to help them.

Ken: Doing the production and session work that I do, I never really choose projects. They all come to me, and they’re all very different. That forces me to adapt. I have a real hunger for wanting to try different things. I find that with the amateurs, there’s a far greater range of interests and diversity, and they don’t have to be pushed into the same formatted commercial kind of vibe. We can explore and make records that we love. There are lots of records that have been made over the years that puzzled the market, and that would include The Velvet Underground and the Ramones, and all these iconic records that the market really didn’t know what to do with. But they’re so important for the general growth of culture. The independent projects that come my way — that’s where so much interesting stuff happens, and I really can’t imagine not having that as part of my working life.

Joe: Clearly, I listened to you all through the ‘90s. But my favorite band is Dinosaur Jr. None of the music I’ve made with Ken or with my other music partner is remotely Dinosaur Jr.-esque. I don’t write like that, but with Ken I’m starting to understand the ethos of being the vessel. There’s a thread there that just worked. There’s no other way to explain it. I take an honest view of most everything, including myself. Realistically, this doesn’t necessarily happen. Like this track coach doesn’t get together with a famous musician and create an EP in one year.

Connect with Joe Puleo: Official | Facebook

Connect with Ken Stringfellow: Official | Facebook | Twitter

Listen to Ten Years To Home: Stringfellow Imagines Puleo