Robben Ford has released his 45th solo album in more than half a century of recording. Aptly titled Pure, it contains nine instrumental tracks and is his first instrumental studio release since Tiger Walk in 1997. I opened my interview with him by breaking one of the once cardinal rules of journalism. I told him exactly what I thought of the CD. I explained that I love blues, but jazz always seemed to cerebral and academic for my taste because I have a lower chakra interest — but that Pure, anchored in jazz, does it for me in both directions which is very, very rare. I summed things up by saying, “nice album.”

He thanked me. “I don’t think anyone has ever said that to me, and it’s a beautiful thing to say.”

The album is clean but gritty at the same time, bluesy but with jazz and classical influences.

“If you listen to classical music, and you’re a musician, you should be influenced by it. So, I’m influenced by everything I really like and listen to and I bring it into my music one way or another, even if it’s only a kernel of what I’m listening to.

“What’s the feeling you want to get out of that instrument, choices of instrumentation, placement, where they want to sit in the mix, all of these things for me is how I’ve been influenced by classical music. I love beautiful melody and texture, you know, nuance? So, from that perspective, the classical music I’ve listened to is in there. The Indian music I’ve listened to, the jazz, the blues. No rock. There’s no rock in there.”

Pure is unlike any recording Robben has ever done. In a press release, he says, “I’ve always been a traditionalist in the way I’ve worked in the studio, bring a great band into a great room with a great engineer, track songs for three to five days, do any overdubbing necessary, then, mix and master. I started Pure in that same way. But, somehow the influence of other musicians on the music, which is inevitable, always felt a little off. It became clear to me that I had to shape this new music myself from the ground up.”

He elaborated in our interview. “What I wanted to do with this record is I had to have full control. The way I wanted it to sound in the end is I wanted it to be exactly what I was thinking or feeling here, and not just accepting what somebody else was thinking or feeling. So, it was a pretty quick decision a couple of times in the studio with some different guys I can’t go through this. Forget it!”

So, he let most of the musicians go and did it himself. This from a five-time Grammy nominee who’s done session work with everyone from Miles Davis and George Harrison to Joni Mitchell and Mavis Staples. I asked him if the session work was painful because in that situation, he has little or no control over what he plays.

“Oh, no,” he said with finality. “It’s always a challenge. It’s not your record. So, you’re there for them, and I’m happy to do that. I’m happy to try and enhance someone else’s music if I can. It doesn’t matter what it is. It’s always a challenge. There isn’t anything I go into with an arrogant attitude.”

In 1990, he did a day with Dylan for the album Under The Red Sky. Producer Don Was called him about the session. “He said, ‘Look, Robben, I gotta tell ya. Every day is a different band. We keep the same rhythm section, bass and drums. Every day is a whole different set of players beyond that, but I’d be glad if you’d come in and play one day.’ I’m like, ‘Hell, yeah!’ So, the sessions were done with the whole band in a room, live of course.

“Bob Dylan was behind two screens that cut down on leakage from microphones. We could see him through the glass. We’re in a semi-circle facing him, and he has a table in front of him with a bunch of harmonicas and a bunch lyric sheets, but it’s just stuff he wrote. It’s like 30 different pages with words on them in front of him on the table with a bunch of microphones. He’s got a guitar, and he would just start playing the guitar, and we all just start playing.

“No one had told me this, but that was how he was making records. So, we would just start following him along, and he would just start playing something else. Ok, and we’d start playing along. and he’d get a vibe going that he’d like, and he’d start fishing around on the table in front of him and trying these words, and he’d try singing them, and he’d (jot) them down and get some more words and try to sing ’em like that. And that’s how those songs were created.

“It was really a unique experience. We did two songs. One of them was ‘Born in Time.’ He had written it on the piano. So, he played it on the piano, and we all learned it. Then he says to the producer in the control room listening to the playback, ‘So, Don, how many takes did we make?’ Ha, ha, ha. A silly thing to say, really. How many takes did we make? Anyway, he goes, ‘Ok, that’s enough.’ Then, he calls a session. He made enough takes. I’m like, ‘No, we can’t be done.’”

The released version of “Born in Time” includes David Crosby on backing vocals, and Bruce Hornsby on piano.

“You just had the feeling you were in this room with history. That’s the only way I can describe it. I’m in the room with history here, and it moves me. I go up to Don, and I say to Don, ‘Don, you gotta let me come back.’ He says, ‘Robben, everybody says that. You can’t do it.’ So, that was my experience with Dylan. I had met him a couple of times briefly when I was out with Joni Mitchell. I met him on the road with Joni. He never said a word to me or anybody else. I was on the road with George Harrison, and he never said a word to anybody else but George. And that’s just the way it was.”

Robben also worked with Lowell George on Little Feat’s Down on the Farm album released in 1979, the year he died. “Lowell was certainly there when I was recording with them, but that was a beautiful recording studio in the Agora Hills outside of L.A. with a recording truck parked outside. l would be out there, and Lowell would come in.

“There were some chats here and there, but he, too, was rather enigmatic and hard to approach. He was heavily into the use of drugs. I remember coming into the room at one point, and I don’t remember what he was doing. He said something to somebody, and I thought (to myself) this guy is dying. The thought just came into my head like that, and six months later, he had died.”

I told Robben I was working on my memoirs and that one of the threads throughout was the concept that there’s a dance between artists and record labels, and that he’d been with a lot of different record labels. Did he want to say something about the difference between record labels 40, 50 years ago vs. 2021 with all the changes in technology?

“Well, not being facetious, they don’t really exist anymore. The world has changed. It’s really in the artists’ hands at this point. I have made this record with earMusic. They are a record label. They even manufacture a produce and everything, but (pause) I don’t want to offend them.”

Ford may say there’s no rock on this album, but he has a rock and roll heart. And a blues heart, a jazz heart and a classical heart. This is a release that takes the listener to all these places beyond earth’s orbit.

Pure

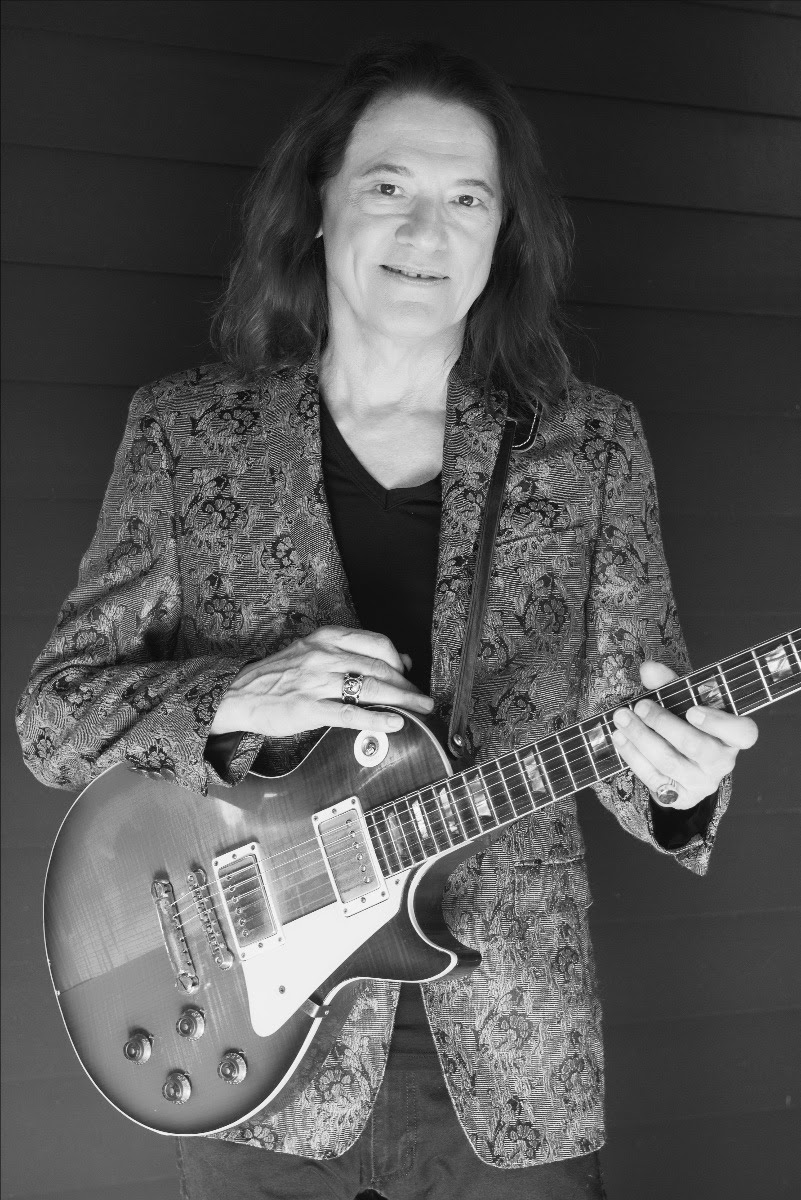

*Feature image photographed live at City Winery Chicago Sunday, August 15 / Credit: © Phil Solomonson (Philamonjaro Studio)