Born in the cauldron of horrors that was slavery, blues as a genre is uniquely positioned to provide humanity with the kind of catharsis we all need to push on through to the other side of the collective nightmare we face in the pandemic. Below are the backstories of five artists who provided us with soundtracks to survival in 2021, the year of our collective discontent, a year that never seemed to end. Their music is the soundtrack to survival of the fittest, beacons in a war against a disease that discriminates against us all regardless of race, gender, or economic status.

The pandemic made recordings significant again in 2021. Many releases had been reduced to what musicians in 2019 had come to refer to as mere “calling cards” for promoters. Captured on the run, these recordings were audio resumes recorded to get gigs that had replaced record sales as the most important source of income.

Starting in March of 2020 with live gigs largely forbidden by pandemic protocols and with time on artists’ hands, recordings became less about catching an artist’s live sound for promotion and more significant in and of themselves. Modern technology made it easier to phone in contributing musician’s parts, and the songs themselves were more thought out by musicians with time on their hands.

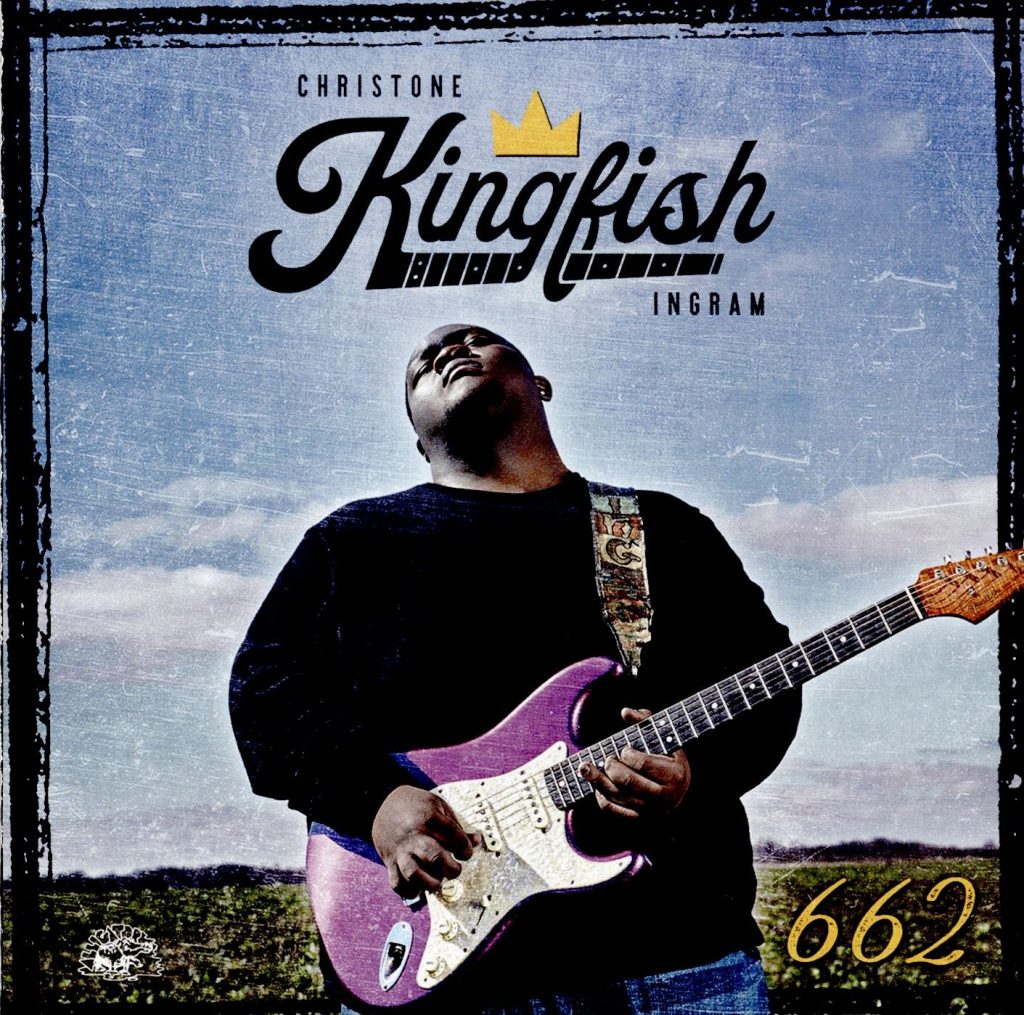

Christone “Kingfish” Ingram released his sophomore album 662 early in 2021. Bruce Iglauer, CEO of Alligator Records, called it one of the most successful releases of that label’s 50 years in the business.

In the liner notes, Kingfish dedicated the record to his mother, Princess Latrell Pride Ingram, who had recently passed away: “Lastly and certainly not least, thank you to Ma. You were always my biggest champion and cheerleader. I know that you’re looking at me with proud eyes and big heart. I miss you. I love you. Thank y’all much!”

Through Princess’ loving care and attention, Kingfish has become one of the youngest artists to rise to the top in blues history. Princess told me in 2018 that her son has Asperger’s Syndrome. “He started learning things on his own. He started listening to the different songs, and he could play the songs, just listening to them. That’s when we realized it was something different with Christone. We later found out he has Asperger’s Syndrome. Anything he hears in music is in his head all the time. It’s music all the time. It’s like his comfort zone. Music is his escape where he can go and hide and be himself because sometimes he’s been in that position where some people don’t like him and that’s his (right) to go into that zone and be himself and escape.”

Princess was prescient in turning what some might call an affliction into the plus it has become in his meteoric rise. “There are some things he doesn’t like to do. Believe it or not, he doesn’t like crowds, and I think Asperger’s has really been an advantage. Asperger’s makes him great, makes him unique. Yeah, so it’s an advantage and disadvantage, but I try to look at it as being more positive than negative. I’m very comfortable talking about it. We travel and I have parents come up to me crying and saying, ‘I have a child like that.”

I told Kingfish in July, 2021 that his mom was very proud of him. “Thank you so much. She was pretty much my number one supporter.” He talked about how 662 was produced. “The album was conceptualized, created and co-written during the Covid-19 pandemic when I returned home to the 662 (his telephone area code in Clarksdale, Mississippi) after a truly whirlwind year of change and growth.”

Kingfish is a native of Clarksdale, ground zero for delta blues. The offspring of parents steeped in the church and the blues, he began playing bass at age eight and guitar at 11. His dad introduced him to blues with a documentary on Muddy Waters. He first toured with Buddy Guy who he calls Mr. when he was 14.

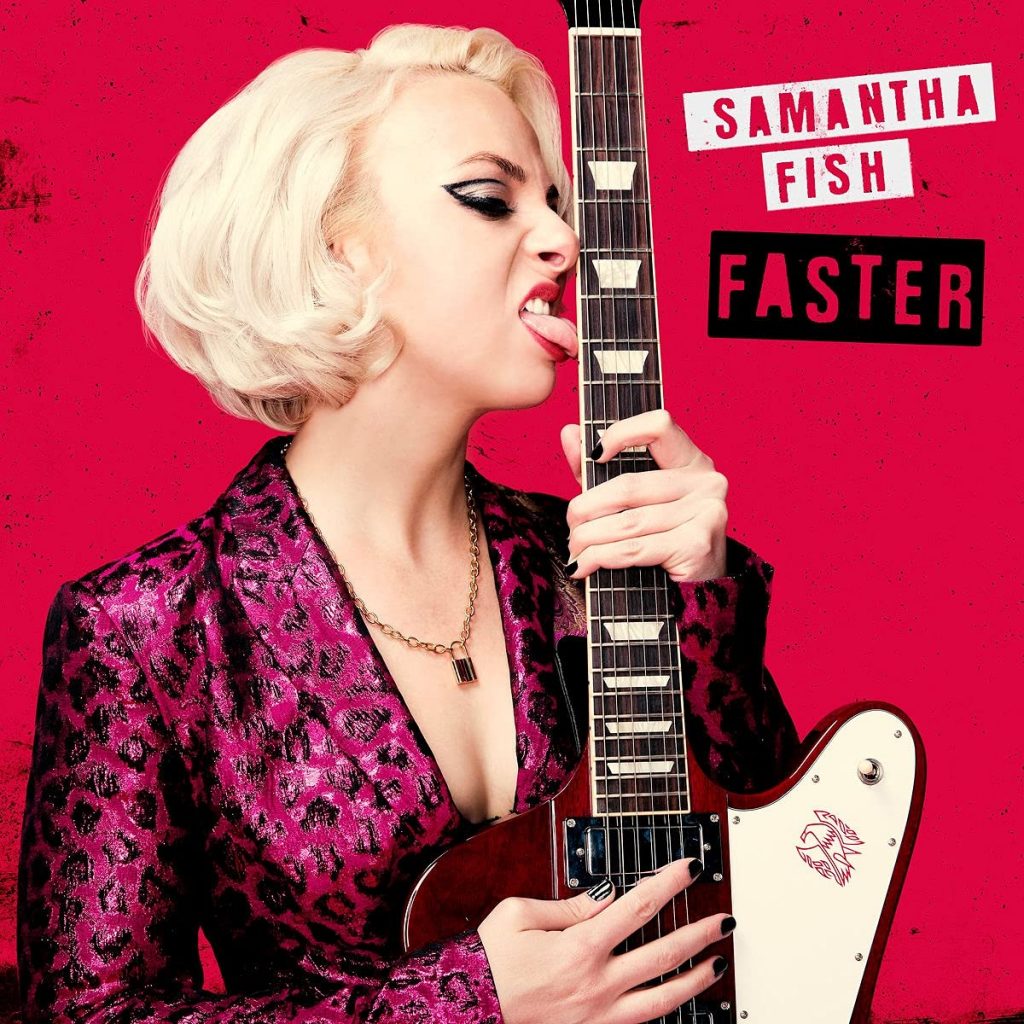

Samantha Fish released Faster in 2021, an album that pushed blues in new directions. I saw her live in September and was blown away by a sound as innovative in capturing the raw edge of the genre as anyone I’d seen since Johnny Winter in 1969 at the Fillmore East. When I called her in August, she was reeling from a devastating Hurricane Ida in Louisiana that had damaged her home, but she was on the road and had no idea how bad the damage was.

“My whole world is (out of) focus right now, but I have to keep moving because we have this new record coming out. I talked to my manager today, and he’s from Louisiana, and he’s like, ‘Hey, this doesn’t stop the show. We gotta keep on.’

“I feel like I’ve got things to take care of that I never got to take care of before the storm, you know? We were out on the road when it hit. So, you can’t get back just yet, and not being able to go and work on it. It’s just killing me to be in the dark essentially. It’s one of those things where it’s gonna get better every day, so we’ll see what we’ve got to do.”

Of the pandemic she said, “Well, once we get to that new normal, I’ll assess it. We gotta get back to normal a little bit before the newness will take over. As much as I want it to be over, it’s not over. We still have a long way to go.

Samantha is used to things not being easy. “I know sometimes some people say pop is a dirty word. I feel it’s a word for a lot of different styles of music, but as far as things go, I definitely wanted to make things that had that soft edge to it, but still the stronghold of the blues but utilized different instruments and electronic aspects of this music to kind of create this – I don’t know – modern sounding thing.

“There’s blowback to everything. If you follow all the rules, there’s blowback to that, too. No matter what you do in this world, there’s blowback. I feel you really have to forge ahead and do what feels good to you and follow your intuition, and that’s really like just do something you can be proud of at the end of the day if your legacy is your sound. There’s always gonna be people who don’t like you.”

In late October I asked Tab Benoit who also lives in Louisiana how many hurricanes he’s been through. His answer? “All of ’em. I don’t know. Shit!

“I had so much work to do around my house, you know? I wasn’t even thinking about it (the pandemic), man. I had a bunch of carpentry stuff I had to get done at the house that I’d put off for 30 years, you know, not wood, just repairs that needed to be done. So, when the shutdown happened, I didn’t shut down. I just worked harder doing different work. I was doing something I needed to do because I knew we’d have to get on the road again, so there was a lot of work. There was months and months and months of being a carpenter. I lost all of my guitar callouses and developed carpenter callouses.”

Tab had been on tour for almost a year when I talked to him. “It’s different everywhere we go. You just don’t know. Every town’s got their own laws, their own rules. You just follow them. Then, you know, I mean we just stopped watching the news, and everything is good, you know? You just stop watching the news, and it doesn’t seem that different than before. Just don’t watch the 24-hour news networks, and we’ll get back to living pretty soon. This thing on the planet works forever. You can’t hide in your house for the rest of your life.”

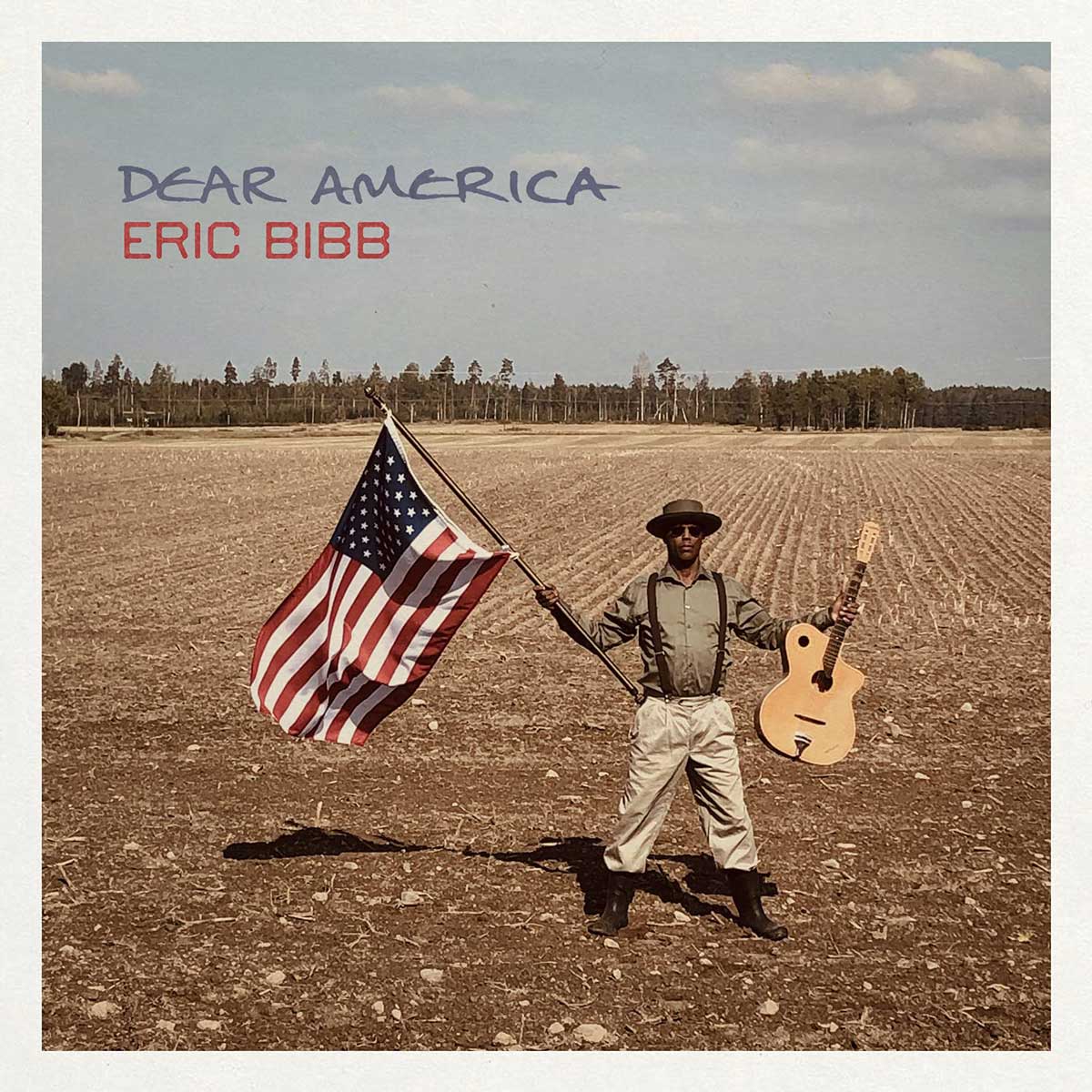

Eric Bibb released an album in 2021 called Dear America. Almost symphonic in its production, the album takes the glove off about what’s wrong in race relations.

On one of the songs, “Love’s Kingdom,” he sings “I found a feather in my coat put there to remind me/Nothing to confine me/I’ve got wings/Wings to fly me as high as my heart desires/above the church spier where the angels sing.” He talked to me about the genesis of that song.

On one of the songs, “Love’s Kingdom,” he sings “I found a feather in my coat put there to remind me/Nothing to confine me/I’ve got wings/Wings to fly me as high as my heart desires/above the church spier where the angels sing.” He talked to me about the genesis of that song.

“It was just an idea that came to me. I take notice of feathers because feathers are somehow like flowers somewhere between this realm and the next or another one. They have some kind of quality that makes you feel like they’re a bridge between maybe this world and the next. So, I’m aware of that whole significance of feathers. The music that has inspired me for so many years, this American roots music, particularly this African American music that inspires me, particularly the African American tradition has so much to do with spiritual and physical survival of a whole people, that whole realm of music is full of – for me – things that cannot be explained in a rational cerebral sense.

“I think we see what we see, and I think there is more to what is than what we see, and I think there is more to what is than what we perceive with our senses, at least the five senses.

“I always want to make a reference to that spiritual quality of that blues tradition because I think it’s essential to the way people have survived. So, I think there have been people all along in this whole long journey who have been aware and sensitive to this other dimension, this spiritual dimension that has informed people who are sensitive enough to pick it up.

“It’s the same kind of person I refer to when I talk about the Samaritan in that song “Different Picture.” There are people who despite all appearances, despite all the brutality that they witness never give up hope – and never give up these links to some other reality.

“I think there’s a reason why all of us have been put together in a kind of collision, sometimes gentle, sometimes very brutal, but I think the idea is we’re supposed to learn from each other, and I think different cultures have different special gifts to share with humanity, and I think it’s all part of what we’re here to learn, and I definitely see that connection to our West African groups in that reference to spirituality that I’m sure many slaves held onto.”

Walter Trout’s “All Out of Tears” from his album Ordinary Madness was the standout song of the standout concert of the year for me. And it’s a prime example of where we all are as a society heading into uncharted territory in the new year. It became the 2021 Song of the Year at the Blues Music Awards.

“It wouldn’t have been on the album Ordinary Madness without my wife. Let me tell you the genesis of that. Me and Marie were in Memphis for the International Blues Challenge. We were walking down Beale St. And we saw (blues singer) Teeny Tucker.

“We said, ‘Hey, Teeny, it’s good to see you. How are you?’ And she told us that her son had just passed away, and we were like, ‘We’re sad to hear that.’ She looked at us and said, ‘My heart is crying, but my eyes are clear because I’m all out of tears.’

“I immediately said to her, ‘Is that lyric from a song? Is that something that you’ve read,’ and she said, ‘No, I’m just telling you how I feel,’ and I immediately said, ‘Let’s write a song about losing a loved one. Let’s use those lyrics, and let’s dedicate that song to your son.’

“So, Marie, Teeny and I wrote that song very quickly. But the thing was the album was already finished. We got home from Memphis. Marie said, ‘You’ve got to put that song on the album,’ and I said, ‘But the album is about done. It’s already mixed. This means I have to rent the studio. I have to get the band and the producer back in there and have the producer mix it. It has to be mastered. Then, we have to add it to the record.’

“And Marie said, ‘Well, whatever you have to do, you have to do it.’

“So, I called the producer, I rented the studio, I called the band. We went in, and we recorded that song in about two hours, pretty much live only because of the insistence of my manager, Marie. Let’s not call her my wife. Let’s call her manager.

“She said to me, ‘That song has to be on there. That song has a universal message because everyone out there has lost or is going to lose someone they love, and that is a universal message you’re giving them. And so I went back in the studio, did the song, and we sent it to the label and said add this to the record, and it ended up winning Song of The Year at the Blues Music Awards, you know?

“So, maybe Marie had the vision of what was coming, you know?”

In our new world of survival of the fittest, we all need therapy to break on through to the other side as Jim Morrison sang so long ago. The arts will hold our hands through the darkness. It is the light that sees us through our own personal nightmares. The blues is our field hollers. It is a helping hand that raises us above being slaves to the pandemic.