I think it was when I was editing BluesWax and FolkWax more than a decade ago that Cary Baker reached out to me on the phone. “I think we should know each other,” he said and then proceeded to sell himself as someone who could help me do more than just fill pages with press releases about the artists he represented.

He read me like an open book. We both came up in a time when public relations for popular music was evolving from nonexistent to the boilerplate five Ws: who, what, when, why, and where. And he retires at a time when print is rare, but the internet is crawling with writers who know so little about the subject matter that they copy press releases word for word, paragraph for paragraph under their own byline.

In my day, that was called plagiarism, but in today’s world its widely regarded as kosher but is one of causes of “fake news.” Fake because it is a common practice for p.r. writers to cherry pick the “facts” of their clients’ background that “prove” these artists were instrumental in developing whole genres of music to become “legacies” and “icons.” The hyperbole is salted with superlative adjectives and quotes taken out of context. It’s all about chart numbers, products sold, and accolades given.

Not Cary.

He knows his clients in some cases better than they know themselves. And he knows the writers and editors who pride themselves on digging deeper into their interview subjects’ backgrounds, beyond the stats, beneath the hyperbole, and into the anecdotes that define those artists’ inner muse.

When I asked Cary to give me a quote about me to help me sell my memoir Even Rock Stars Get The Blues, he wrote “I met Don Wilcock literally on a levee in the Mississippi Delta — more accurately at the King Biscuit Festival in Helena, Ark. many moons ago — and knew right away that his passions for blues and other roots music ran deep. What I’ve come to learn since then is that his journalistic chops run equally deep. A veteran music journalist, of the type they simply don’t make anymore.”

He knows Don Wilcock as an individual, and he was able to sum me up in one short paragraph, the kind that says more about a person than some entire book length biographies. And that’s the game that’s gotten lost in the plethora of plagiarized press releases written by neophytes who are mere conduits, temporary secretaries who set up half-hour interviews with touring acts, interviews that are strung together in daylong marathons where the artist is tutored on what to say to put asses in the seats.

Some would call people like Cary and me “dinosaurs.” Others sum us up as “old school.” Both are put-downs. I think of people like Cary and me as artists of the spoken word. We’re plying the same depths as the artists we’re privileged to get to know. Our job is represent them as real people, not product.

That’s why I write for American Blues Scene. This publication rises above the fray.

I’m going to miss Cary.

A lot!

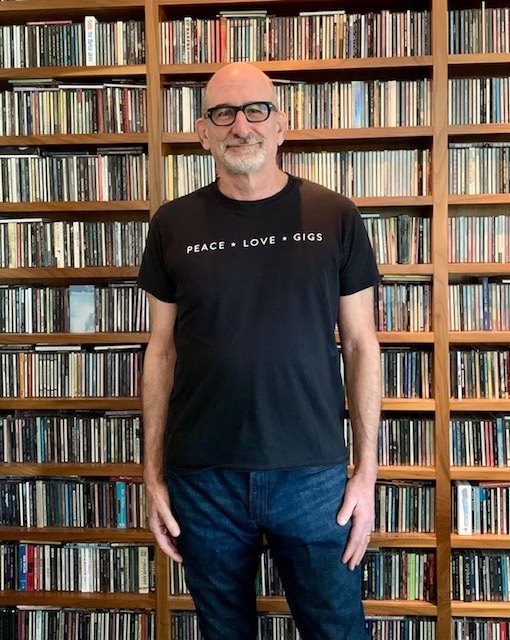

Editor’s note: Below is Cary Baker’s March 4th press release, a recap of his 42 years in music publicity.

My career in music publicity has spanned 42 years, six record labels (publicity chief at Capitol, I.R.S., Morgan Creek, Discovery, Enigma and Ovation), and three independent publicity companies including the firm I’ve operated since 2004, Conqueroo.

It all began in Chicago during my high school years (1969-73). I became very interested in blues, of which my hometown was a hub. I sent the Chicago Reader an unsolicited, typed manuscript about a blind street singer and slide guitarist named Blind Arvella Gray, who played every Sunday in the city’s Maxwell Street district, and it ran as a feature in the neophyte alt-weekly. That led to additional freelancing. While studying journalism at Northern Illinois University, I wrote about music for the college newspaper as well as for Creem, Living Blues, Illinois Entertainer, Bomp!, and Prairie Sun. Inspired by the DIY movement, I also launched a small indie label from my college apartment called Fiction Records. I simultaneously edited an alt-weekly in Rockford, Ill., where the biggest story in town was the emergence of hometown band Cheap Trick (who became my longtime friends).

On graduating and moving back to Chicago, I wrote for Billboard magazine, which then maintained a downtown Chicago office. My editor had astute news reporting sensibilities and routinely sent me back to the IBM Selectric for many a re-write. I owe him a lot. My story about Glenview, Ill. country music, jazz and quadraphonic label Ovation Records — announcing its foray into pop and rock — resulted in me being recruited as that label’s National Director of Publicity and Advertising. I accepted, and learned much about country music thanks to the label’s Music Row office, whose roster included The Kendalls, Joe Sun, Vern Gosdin. (Ovation also released DJ Steve Dahl’s infamous disco parody, and some pop releases by Tantrum, Robbin Thompson Band and Citizen.) My desk was equipped only with a telephone, typewriter, Rolodex and (importantly) coffee. That’s all one needed in those days.

Following a layoff at Ovation’s Chicago office in 1981, I spent three years freelancing (adding Trouser Press, Mix, Hit Parader and Jann Wenner’s Record magazine as outlets) along with handling PR for the Chicago venue called Tuts. In 1984, I heard of a job opening for Publicity Director at one of my favorite labels on earth, I.R.S. Records. I applied, and so did 60 others. I flew to Los Angeles, interviewed, and was asked to make the move — and pronto, as the label was readying new albums by R.E.M., the Go-Go’s, and the Alarm. It was amazing to work on the A&M Records Lot (I’ll never forget walking to my car after work one night and hearing Herb Alpert’s trumpet wafting from a nearby office) and, when the company moved, at Universal Studios. I became part of the team that broke R.E.M. (I pitched their first Rolling Stone and SPIN covers and Saturday Night Live appearance), as well as Timbuk3 (also on SNL), Concrete Blonde, Fine Young Cannibals, General Public, and The dB’s. My boss, label president Jay Boberg, became a mentor and friend. It was an unforgettable four years!

I moved on to Capitol Records in 1988, heading the bicoastal publicity department of eight people — a new challenge for one not schooled in staff management. While at the Capitol Tower on Vine Street, I worked closely with Bonnie Raitt, the Smithereens, Tina Turner, the Beastie Boys, Johnny Clegg & Savuka, and Donny Osmond. I was there when Raitt won her many Grammys for Nick of Time, the Smithereens broke onto SNL, and the Beastie Boys were feted on the roof of the Capitol Tower for an album release launch party. Paul McCartney released his Flowers in the Dirt album in that window as well.

I left in 1991, concluding that corporate politics was probably not my forte, I returned to my indie roots and took a job as VP Publicity at Enigma Records. David Cassidy was the priority du jour, and he too got his shot on SNL on my watch. Around this time, several new labels were being launched: Interscope, Zoo, Imago, Hollywood, and Morgan Creek Records. I submitted a résumé into the last, a division of the film studio Morgan Creek Productions. And while it ultimately fell short of Interscope’s sky-high trajectory, it launched with a platinum hit from the Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves soundtrack (Bryan Adams) and worthy albums from Shelby Lynne, Janis Ian, Little Feat, Eleven, Mary’s Danish, and Miracle Legion. Highlights were Late Show With David Letterman appearances by the two latter bands.

My work with Shelby Lynne was noticed by a few Nashville titans. So when Morgan Creek dissolved its label division, I went to Nashville and met with Sony Music and Garth Brooks’ former manager Pam Lewis. I ended up working from the West Coast bureau of Pam’s PLA Media. My job included business development as well as publicity, and I brought in clients like Rykodisc’s, Motown’s and EMI’s catalog divisions, Frank Zappa and Ringo Starr’s catalogs, John Mayall, and Raffi. I learned much from Pam about running an indie PR shop, and PLA Media thrives to this day.

When I got itchy to work at a label again, I moved to Warner Music Group’s Discovery Records, whose chairman was Elektra Records founder Jac Holzman. There I worked on projects by Bernie Taupin’s Farm Dogs, Too Much Joy, Candye Kane, Antone’s Records, Willy DeVille, and a duo I helped sign to the label, the Finn Brothers (I’d worked with Tim Finn and Neil Finn’s Crowded House while at Capitol). Three years in, I was among those laid off in a corporate reorganization. By now, I was used to this.

Partnering with a longtime PR colleague, I co-founded the Baker/Northrop Media Group in 1998. Our clientele included Robert Cray, Cheap Trick, Yes, Delbert McClinton, HBO’s Reverb program, and a young, then-unknown, blues-based artist named Susan Tedeschi. On our watch, Tedeschi gleaned much buzz, culminating in a gold-certified debut LP and a 2000 Grammy nomination for Best New Artist.

My next (and final) act in music publicity was to fly solo. I launched Conqueroo — its name derived from Chicago blues lyrics as a nod to my origins — and became busier than ever. First came singer-songwriter James McMurtry in aught four with his album Live in Aught Three. James became Conqueroo’s steadiest client, and I believe we helped him carve a national presence in the media. Then came blues legend Bobby Rush, Willie Nile, Janiva Magness, Chris Hillman, Billy Joe Shaver, Kinky Friedman, Rodney Crowell, Nils Lofgren, Paul Kelly, Colin Hay, the Mavericks, the Hoodoo Gurus, Peter Himmelman, Ruthie Foster, Van Dyke Parks, Dan Penn, Swamp Dogg, Freedy Johnston, Marshall Crenshaw, Tommy Keene, The dB’s, Cidny Bullens, Rev. Peyton’s Big Damn Band, Jim White, Chuck Mead, Eilen Jewell, Tom Freund, Concord/Craft, BMG, Bear Family, and Proper/Last Music, among hundreds of others. Conqueroo became one of the pre-eminent roots, Americana, blues, power pop, reissue and music-book publicity companies in America! We had numerous Grammy nominations and wins in our 18 years.

One of Conqueroo’s trademark clients — an entity that became something of a second family for me — was Omnivore Recordings, which I began to represent in 2011. Omnivore presented a roster befitting its name: Alex Chilton/Big Star, Buck Owens, Jeff Tweedy, Urge Overkill, Art Pepper, Townes Van Zandt, Old 97s, the Dream Syndicate, Lone Justice, Lloyd Cole, The Posies, Trip Shakespeare, Game Theory, Les McCann, Camper Van Beethoven, The Muffs, The Continental Drifters, The dB’s, Chris Stamey and Peter Holsapple, Tim Buckley, Peter Case, Allen Ginsberg, Hasaan Ibn Ali, Dennis Coffey, The Rave-Ups. Omnivore satisfied my craving for so many musical food groups. I learned much about artists, labels, and repertoire of which I hadn’t been previously aware.

In 2006, I was named Publicist of the Year at The Blues Foundation’s Keeping the Blues Alive awards. I returned to the podium in Memphis with Bobby Rush, his manager, Jeff DeLia, and the Omnivore folks when the bluesman’s retrospective box set (Chicken Heads: A 50-Year History of Bobby Rush), which we all co-produced, won Historic Album of the Year in the 2017 Blues Music Awards. Conqueroo of course was not just me. Within a year of launching the company, I realized I needed help — especially in keeping up with our artists’ tours (especially that of the ceaselessly itinerant McMurtry). Julie Arkenstone came aboard 13 years ago and is the best tour publicist with whom I’ve ever worked. Brian O’Neal and Wendy Brynford-Jones joined as national publicists, enabling us to take on more artists. They’ve all become great friends and loyal associates. I can’t recommend them highly enough!